Abstract

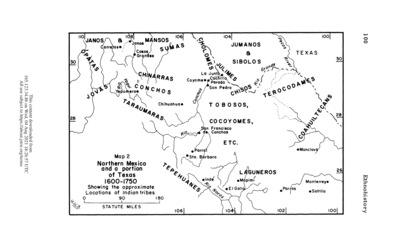

In the story of colonization, enslavement, forced migration, and racism that were and are foundational to the construction of the Americas, there was in fact no single “event” nor one ‘arrival” that simultaneously altered continents. Nor did these arrivals, stumblings, and accidents of European presence alter the heterogenous, overlapping, and diverse groups of Indigenous people in the same manner. In other words, the serial arrivals and enfolding of Spaniards within the Americas was not the immediate end, nor the full “collapse” of societies– it was, however, a drastic change that affected people, their families, and their cultures in ongoing and layered aftermaths of colonization, racial capitalism, and cultural genocide. As soon as Spaniards arrived, there was always resistance, new braidings of knowledges, and language and cultural practices that persisted. The generations of Spanish arrival, did, however, characterize a profoundly new chapter for many citizens and inhabitants in the Americas.

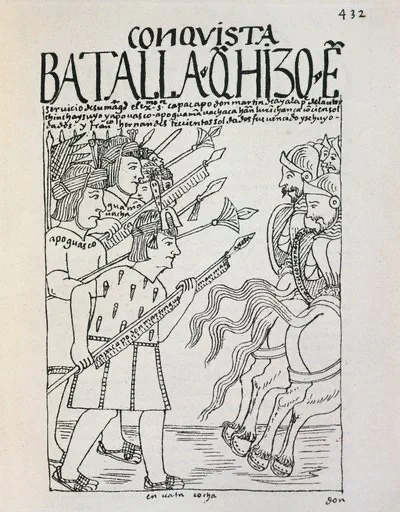

There is no single event, nor one arrival, that simultaneously altered the Americas.1 The serial arrivals and enfolding of colonists from Europe and elsewhere within the Americas was not the immediate end, nor the full “collapse2” of societies– it was, however, a drastic change that affected people, their families, and their cultures in ongoing and layered aftermaths of colonization, racial capitalism3, and cultural genocide. As soon as colonists arrived, there was resistance, new braiding of knowledges4, and language and cultural practices that persisted and were fought for. The generations of Spanish arrival, did, however, characterize a profoundly new chapter for many citizens and inhabitants in the Americas.

Statistics do not always capture the granularity of loss. It is very unlikely that we will fully understand the extent to which war, capitalism, slavery, and disease changed the populations of the Americas, and scholars have debated for more than a century about the loss of lives between 1492 and 1900.5 Scholars have attempted to reconstruct the number through analyzing carrying capacities of land(or how many calories each parcel of farmed land could supply a population),6 or quantifying relative population densities and multiplying it by space7 or using a host of colonial census data8 to estimate how many people were living throughout the colonial world. While all imperfect, their estimates reveal that through genocide, disease, and violence, people lost their lives in complex and drastic ways, culminating in a hemispheric genocide of “unmatched proportions.”9 Even colonial Spanish authorities estimated that a century after Spanish presence, nearly a third of Indigenous populations had perished.10

Currently there is a consensus that the Indigenous population of the Americas was decimated by as much as 90% in the aftermath of colonization, a number that reduced nearly 100 million people to just 10 million.11 Disease played an enormous role in this decimation, but it should not be thought of as a separate entity. Rather, disease should be thought of as a more elusive form of biological warfare, a weapon in the arsenal of colonization. As Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz argues, disease alone did not do the job- it was only through the landscape of warfare, forced labor, and revolt that the conditions for disease were optimized for its takeover.12 The aftermath should also not be negated. Massimo Livi Bacci argues that in addition to abuse, the systematic disruption of Amerindian life through dissolving familiar, economic, and social ties led to immense population decline.13

Central to the conditions of loss was the institution of slavery and indenture, and their enmeshment in capitalist extractivism. From 1501 to 1650, an estimated 726,000 African people were kidnapped and enslaved in the Americas by Portuguese, and later Dutch elites.14 This number is eclipsed by the next era of enslavement, in which English and French elites controlling sugar and tobacco plantations kidnapped and enslaved about 4.8 million people from the African continent; in the following century, until, but not completely stopping, in 1866, another 5.1 million people were sold into slavery and brought into the Americas15.

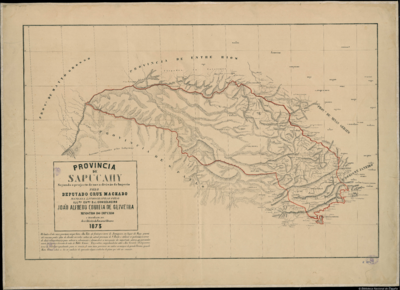

The city of Potosí, in modern day Bolivia, became the world’s largest silver mine in the mid 17th century, and also one of the largest cities in the world- in over three centuries of mining, an estimated 8 million Indigenous people from the region now forming Peru, Bolivia, and East Africa were killed through unsafe mining conditions and labor.16

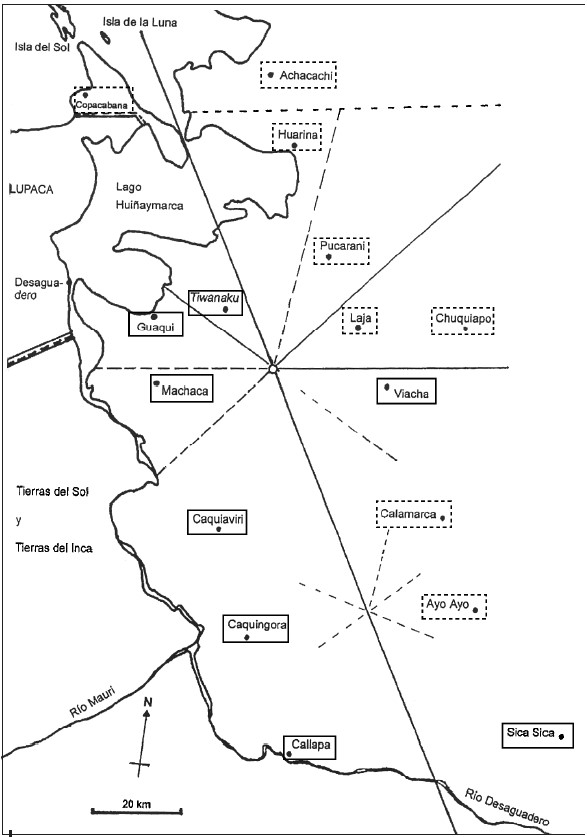

To speak of a post-colonial moment erases the ongoing internal colonialisms17 that came to encompass economic and social systems. The story of the Americas, and that of the current worlds that we inhabit, are embedded in logics of coloniality. At the same time, we must also be aware that coloniality was often negotiated and was and is an ongoing relationship. We cannot simply think of colonial orders as perfect exports from one system onto another, but rather as systems that emerged in response to, in appropriation of, and sometimes in tandem and alliances with Indigenous systems.18 Our current world order, nationhood, and self-determination, are also products of revolt, resistance, and fights for justice.

Bibliography

Dean,C. & Leibsohn, D “Hybridity and Its Discontents: Considering Visual Culture in Colonial Spanish America” Colonial Latin American Review, 12:1(2003): 5-35.

Denevan, W. M. Estimating Amazonian Indian Numbers in 1492. Journal of Latin American Geography, 13(2),(2014): 207–221

Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. An Indigenous peoples’ history of the United States. Vol. 3. Beacon Press, 2014.

Englert, Sai. “Accumulate, Accumulate!” In Settler Colonialism: An Introduction, 26–78. Pluto Press, 2022.

Koch, Alexander, Chris Brierley, Mark M. Maslin, Simon L. Lewis, “Earth system impacts of the European arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492”, Quaternary Science Reviews, Volume 207, (2019):13-36.

Liebmann, Matthew J., Joshua Farella, Christopher I. Roos, Adam Stack, Sarah Martini, and Thomas W. Swetnam. “Native American Depopulation, Reforestation, and Fire Regimes in the Southwest United States, 1492–1900 CE.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, no. 6 (2016): E696–704.

Livi Bacci, Massimo Conquest: the Destruction of the American Indios. Translated from italian by Carl Ipsen. Cambridge, UK and Maiden, MA: Polity 2008.

Malpass, Michael A., and Sonia Alconini. “Provincial Inka studies in the twenty-first century.” Distant provinces in the Inka Empire. Toward a deeper understanding of Inka imperialism (2010): 1-13.

Moreton-Robinson, Aileen: The White Possessive:Property, Power,and Indigenous Sovereignty. Minneapolis University of Minnesota Press (2015)

Projit Mukharji Doctoring Traditions: Ayurveda, Small Technologies, and Braided Knowledges. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 2016.

David Reher “Reflections on the Fate of Indigenous Populations of America” Population and Development Review 37 no. 1 (2011): 172-77.

Robinson, Cedric. Black Marxism: the Making of a Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.1983.

Tallbear, Kimberly and Jenny Reardon, esp. “Your DNA is our History”: Genomics, Anthropology, and the Construction of Whiteness as Property. Current Anthropology. V 53 no 5 April 2012: S233-S245.

Quijano, Anibal. “Coloniality of power and Eurocentrism in Latin America." International sociology 15, no. 2 (2000): 215-232.

As scholar David Truer notes, “The colonization of North America is often seen as a binary struggle, a series of conflicts between Indians and settlers. But in the fact of disease, starvation, and displacement, conflict occurred along multiple vectors. Tribes allied with other tribes against yet other tribes; colonial powers made alliances with certain tribes against other tribes and against other colonial powers.” See David Truer (2019). Some Indigenous groups gained more authority under Spanish control when Indigenous kingdoms like the Inka empire fell. See Malpass, Michael A., and Sonia Alconini. “Provincial Inka studies in the twenty-first century." Distant provinces in the Inka Empire. Toward a deeper understanding of Inka imperialism (2010): 1-13. Other demographics fared far worse: when viewed with the critical lens of gender, Indigenous women suffered in distinct ways, and in colonial logics were made, legally, the property of men. See Englert 2022: 45. ↩︎

Many scholars work against the term “collapse” because it conjures ideas of total erasure. Many times the idea of total erasure of populations has been used against Indigenous survivors of colonial violence. More specifically, many colonial authorities used the term to take people’s land and cultural heritage sites and artifacts under the assumption that no one was left to care for them. This is untrue, and many continue the fight to reclaim stolen land and heritage objects, and in many cases, their own bodily autonomy. For how this effected land and territory, see Ailieen Moreton-Robinson’s the White Possessive:Property, Power,and Indigenous Sovereignty. Minneapolis University of Minnesota Press (2015). For how uncritical notions of “hybridity” have disenfranchised Indigenous people, see work by Kimberly Tallbear and Jenny Reardon, esp. “Your DNA is our History”: Genomics, Anthropology, and the Construction of Whiteness as Property. Current Anthropology. V 53 no 5 April 2012: S233-S245. ↩︎

The term “racial capitalism” is a famous term coined by theorist Cedric Robinson. The term refers to how current systems of capitalism cannot be divorced from histories of slavery, and how unequal economic conditions became increasingly forged around social perceptions of race. See Cedric Robinson Black Marxism: the Making of a Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.1983. ↩︎

The term “braided knowledge” comes from Projit Mukharji, and refers to the way in which understandings, practices, and knowledges often influence each other such that they entwine into something new. Projit Mukharji Doctoring Traditions: Ayurveda, Small Technologies, and Braided Knowledges. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 2016. See also scholars that write critically on the notion of “hybridity” in which two parts are seen as distinct that are brought together. Many point to the fact that classifying practices and ideas as either just Indigenous or Spanish actually disserves us, as we then do not take art, religion, and worldviews as wholistic, but rather syncretic. See Carolyn Dean and Leibsohn “Hybridity and its Discontents: Considering Visual Culture in Colonial Spanish America” Latin American Review volume 12 no 1 (2016):5-35. ↩︎

Matthew Liebmann et al “Native American Depopulation, Reforestation, and Fire Regimes in the Southwest United States, 1492–1900 CE.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, no. 6 (2016): E696–704. ↩︎

Some studies suggest that after areas were abandoned post 1492 and lands grew fallow, that there was actual measurable amounts of carbon uptake, in that the growing of trees and plants actually impacted the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere In this case it is through the record that the earth keeps, in its Antarctic ice cores and pollen records that we can understand how the carrying capacity of lands must have been so enormous that what has been termed as “great dying” of people left atmospheric traces. See Alexander Koch et al, “Earth system impacts of the European arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492”, Quaternary Science Reviews, Volume 207, (2019):13-36. ↩︎

Denevan. William M. Estimating the Native Population of the Americas in 1492. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. 1992. ↩︎

William Denevan, the Native Population of the Americas in 1492. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. 1992:14. ↩︎

Englert, Sai. “Accumulate, Accumulate!” In Settler Colonialism: An Introduction, 26–78. Pluto Press, 2022. ↩︎

Englert Settler Colonialism: p35. ↩︎

It was a disaster of such magnitude that the often-cited example of the 17th century Black Death in Eurasia completely “pales in comparison” David Reher “Reflections on the Fate of Indigenous Populations of America” Population and Development Review 37 no. 1 (2011): 172-77. ↩︎

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous peoples’ history of the United States. Vol. 3. Beacon Press, 2014. ↩︎

Massimo Livi Bacci Conquest: the Destruction of the American Indios. Translated from italian by Carl Ipsen. Cambridge, UK and Maiden, MA: Polity 2008. ↩︎

Englert Settler Colonialism: pp 58-59. ↩︎

Englert Settler Colonialism: pp 58-59. ↩︎

Englert Settler Colonialism: p 46. ↩︎

Anibal Quijano “Coloniality of power and Eurocentrism in Latin America." International sociology 15, no. 2 (2000): 215-232. ↩︎

Moreton Robinson The White Possessive. ↩︎