Abstract

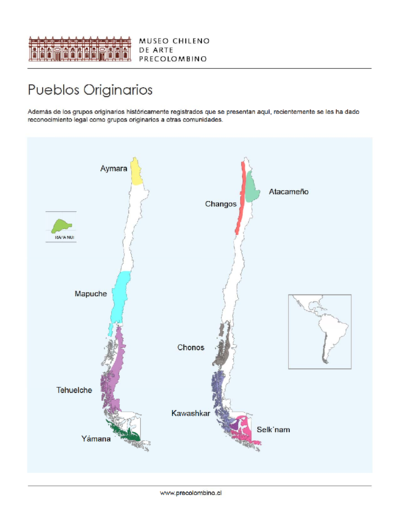

Native, First Nations, Pueblos Originarios and Indigenous people live, and have lived in this land that bears many names; Turtle Island, Tawantinsuyu, and the Americas, among others, for at least between 11,500 and 20,000 years before present.1 Archaeological evidence from 20,000 years ago shows that people were making their lives as far north as the Meadowcroft shelter in what is now Pennsylvania, in the United States, to cave dwellings as far South as what is now called, by some, Monte Verde, Chile.2 But archaeology is but one way to understand time. According to many philosophers and historians, in many ways Indigenous peoples have always been present upon the land3, and have helped shape the land as we know it today.4

The story of the Americas represents an incredibly long, shifting, and complex narrative of many interactions between groups pre-European arrival.5 While peoples’ histories were anything but static, the accidental arrivals6 shifting political ties, and colonization characterized by European presence drastically altered life; just how many people were present in this hemisphere in 1491, and how many people lost their lives post European presence? Scholars rely on a host of different data sets to reconstruct the numbers, from colonial census documents7, to estimating carrying capacities of land8, to changes in measurements of carbon in the earth’s atmosphere.9

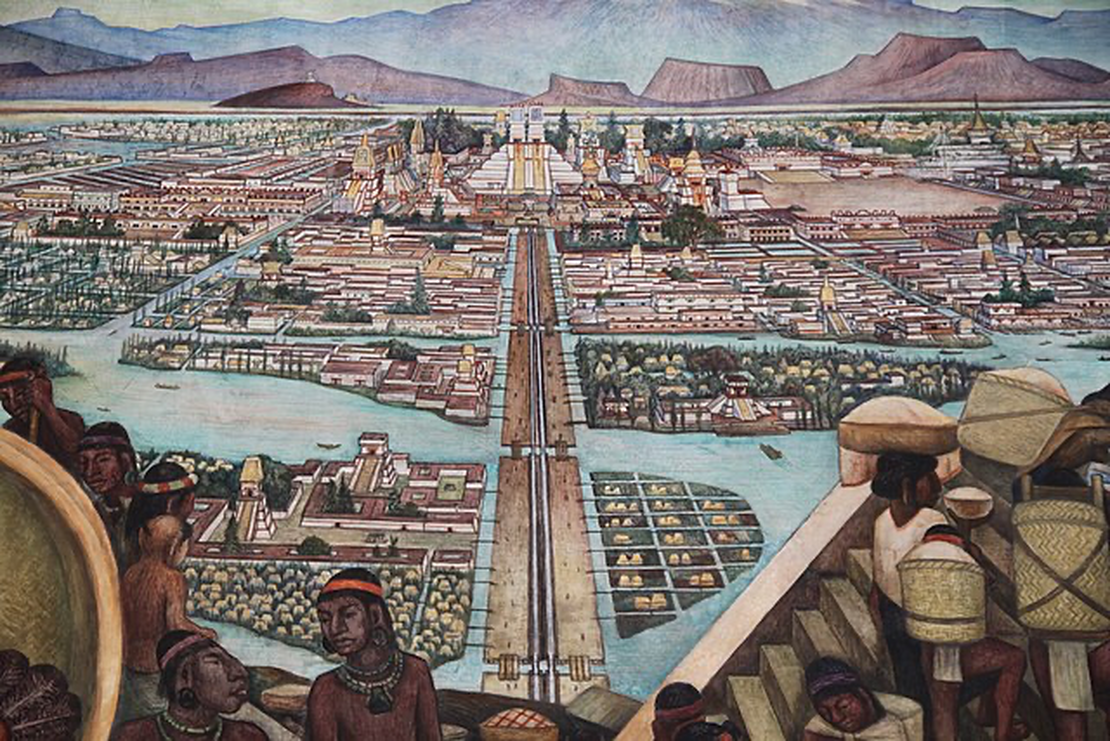

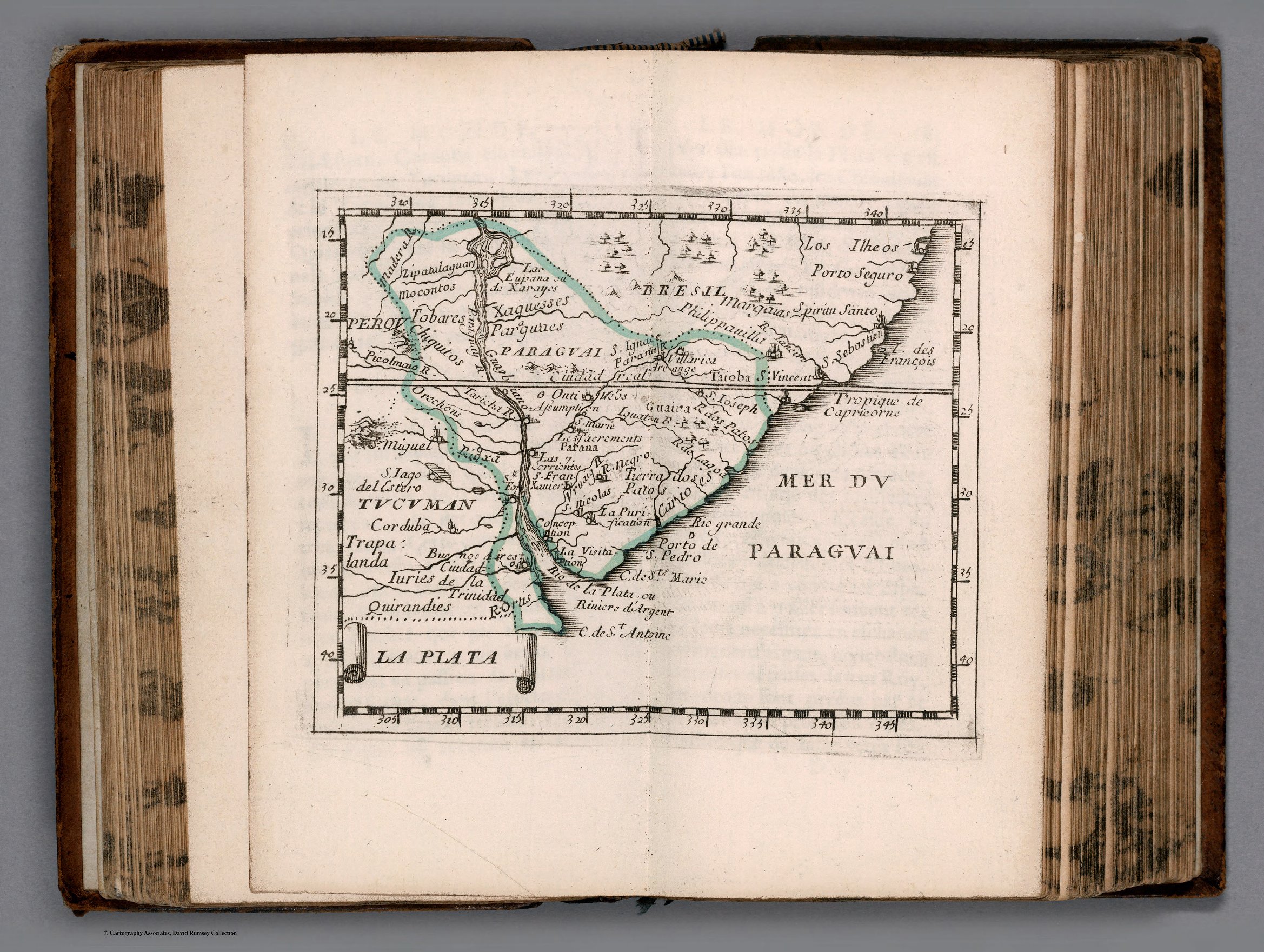

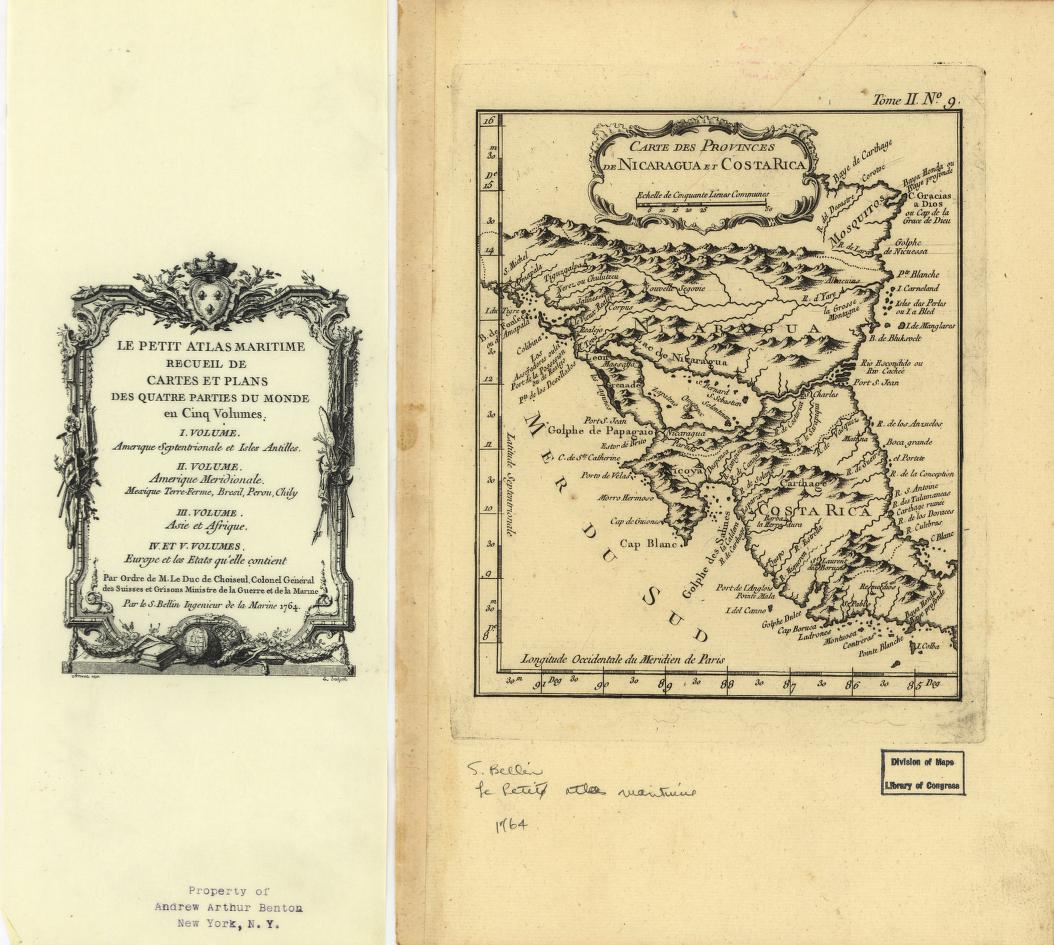

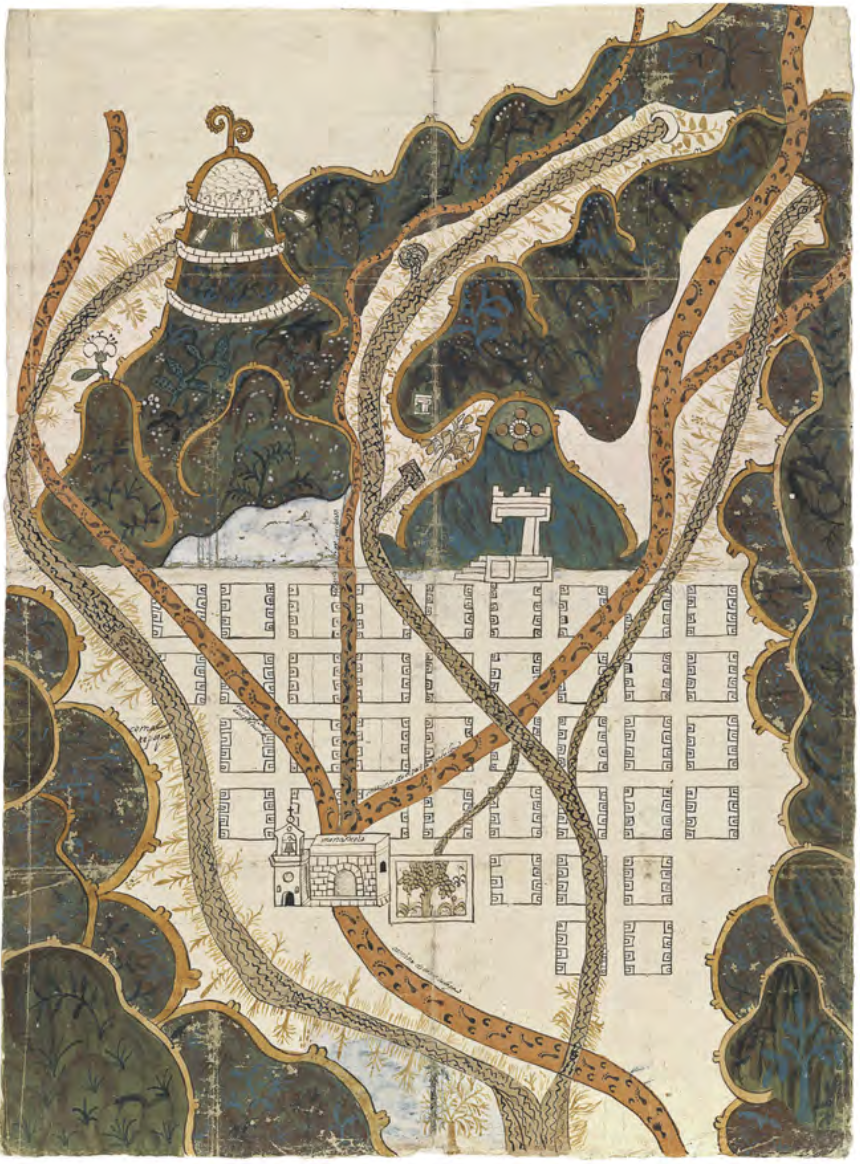

Through stitching together all of these data, there is a general consensus that the Indigenous population in the Americas was nearly 100 million people at the time of Spanish contact.10 When inhabitants of Guanahani found Columbus docked at the shore of the Island now called Haiti and the Dominican Republic, there were nearly 4 million people who lived there and engaged in a huge Caribbean economy of travel and exchange.11 In 1491, the valley of Central Mexico may have been the most densely populated place on earth, with 25.2 million people in 200,000 square miles.12 Tenochtitlán, the imperial city of the Triple Alliance13, was an architectural wonder14 constructed on an artificial lake and held a population amidst pyramids, plazas and public buildings15, a capital city supporting about three million people of the Mexica empire.16 The Amazon basin, channeled by inhabitants into a series of canals, platforms, mounds17, and villages, was an agro-forestry system18 that sustained upwards of 6 million people. 19 Southward, the Inka empire, or Tawantinsuyu, was a four-state system spanning from the North of Argentina to the Southern section of Colombia. It was united by one of the oldest, and the longest road systems in the world, called the Qhapac Ñan.20 The road united a series of capital cities, and a carved landscape of aqueducts, drainage systems, and terraces yielded robust agricultural systems that fed nearly 11,000,000 people.21

Capturing the statistics of populations in this particular time in human history is complex. One fact, however, is certain. These were never empty lands. Rather, emperors, civilians, scientists, and philosophers enfolded Columbus into their own complex histories and infrastructures. The hemispheric part of the world in 1491 was a swarming, interconnected series of empires, states, cities, and settlements with unique histories and names that most likely outnumbered populations in Europe.22 Throughout the next century these places, people, and stories would become enfolded by the European imagination into what came to be called The Americas.

Bibliography

Beltraõ M. C. de M. C. “Datacres arqueológicas mais antigas do Brasil.” Annais de Academia Brasileira de Ciencias 46, no.2: (1974): 212-251.

Cook, Sherburne Friend, and Lesley Byrd Simpson. The population of Central Mexico in the sixteenth century. Vol. 31. Berkeley, U. of Calif. P, 1948.

Covey, R. Alan, Geoff Childs, and Rebecca Kippen. “Dynamics of Indigenous Demographic Fluctuations: Lessons from Sixteenth-Century Cusco, Peru.” Current Anthropology 52, no. 3 (2011): 335–60. https://doi.org/10.1086/660010.

Denevan, William M. “The Pristine Myth: The Landscape of the Americas in 1492.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 82, no. 3 (1992): 369–85. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2563351.

______________ Estimating the Native Population of the Americas in 1492. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. 1992.

Dillehay, Tom D., Gerardo Ardila Calderón, Gustavo Politis, and Maria da Conceicao de Moraes Coutinho Beltrão. “Earliest hunters and gatherers of South America." Journal of World Prehistory 6 (1992): 145-204.

Dobyns, Henry F. “An Appraisal of Techniques with a New Hemispheric Estimate.” Current Anthropology 7, no. 4 (1966): 395–416. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2740306.

Englert, Sai. “Accumulate, Accumulate!” In Settler Colonialism: An Introduction, 26–78. Pluto Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2x6f052.6.

Erickson, Clark L. “8. The Domesticated Landscapes of the Bolivian Amazon.” In Time and complexity in historical ecology, pp. 235-278. Columbia University Press, 2006.

Guidon, N., and Delibrias, G. “Carbon-14 dates point to man in the Americas 32,000 years ago” Nature 321 (1986): 769-771.

Howey, Meghan CL. ““The question which has puzzled, and still puzzles”: How American Indian Authors Challenged Dominant Discourse about Native American Origins in the Nineteenth Century.” American Indian Quarterly 34, no. 4 (2010): 435-474.

Kimmerer, Robin. Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge, and the teachings of plants. Milkweed editions, 2013.

Koch, Alexander, Chris Brierley, Mark M. Maslin, Simon L. Lewis, “Earth system impacts of the European arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492”, Quaternary Science Reviews, Volume 207, (2019):13-36.

Lee, Jongsoo. “The Aztec Triple Alliance: A Colonial Transformation of the Prehispanic Political and Tributary System.” In Texcoco: Prehispanic and Colonial Perspectives, edited by Jongsoo Lee and Galen Brokaw, 63–92. University Press of Colorado, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wrrdm.8.

Liebmann, Matthew J., Joshua Farella, Christopher I. Roos, Adam Stack, Sarah Martini, and Thomas W. Swetnam. “Native American Depopulation, Reforestation, and Fire Regimes in the Southwest United States, 1492–1900 CE.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, no. 6 (2016): E696–704. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26467696.

Livi Bacci, Massimo Conquest: the Destruction of the American Indios. Translated from italian by Carl Ipsen. Cambridge, UK and Maiden, MA: Polity 2008.

Mann, Charles C. 1491 New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus New York: Alfred A Knoph, 2005.

Montenegro,V. A. Mostajo de Muente, P. Mostajo de Muente

La Situacion Poblacional Peruana: Balance Y Perspectivas. Technical Report Instituto Andino de Estudios en Población y Desarrollo, Lima (1990).

Mundy, Barbara E. “Mapping the Aztec Capital: The 1524 Nuremberg Map of Tenochtitlan, Its Sources and Meanings.” Imago Mundi 50 (1998): 11–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1151388.

Quilter, Jeffrey. The ancient central Andes. Taylor & Francis, 2022.

Reher, David S. “Reflections on the Fate of the Indigenous Populations of America.” Population and Development Review 37, no. 1 (2011): 172–77. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23043267.

Truer, David. “ David Truer on the Myth of an Edenic Pre-Columbian “New World”: Indigenous American Civilizations are far Older and More Complex than history suggests.” Literary Hub 2019.

Some archaeologists believe that giving the timing of how sites were populated that the estimate should be upwards of 40,000 years ago. Tom Dillehay et al, “Earliest hunters and gatherers of South America,” Journal of World Prehistory no 6. 1992:150. See Also Beltraõ 1974, Guidon and Delibrias 1985. ↩︎

Dillehay et al “Earliest hunters and gatherers of South America.”; David Truer “ David Truer on the Myth of an Edenic Pre-Columbian “New World”: Indigenous American Civilizations are far Older and More Complex than history suggests.” Literary Hub 2019. ↩︎

Many scholars, including those since the 1850s, have shown that a European obsession with understanding native origins had the motive to dispossess people of their lands, by arguing that everyone in the Americans came from elsewhere. As Meghan C. L Howey writes, three Anishinaabeg writers, Kahkewaquonaby, Kahgegagahbowh, and William Whipple Warren fought dispossession logics and argued that they were a “spontaneous people” meaning that they emerged with the land and could not be seen as separate from it. See Mechan Howey “The question which has puzzled, and still puzzles,” How American Indian Authors Challenged Dominant Discourse about Native Origins in the 19th Century.” American Indian Quarterly, Vol 34. No. 4 (Fall 2010) pp. 435-474. University of Nebraska Press. ↩︎

Howey “The Question that Still Puzzles”; Robin Kimmerer Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teaching of Plants(Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions 2013). ↩︎

There are plenty of relationships archaeologically that show vast trade networks- as early as 1000 A.D, North America had been traversed along the North and South; as Charles C Mann explains, “mother of pearl from the Gulf of Mexico has been found in Manitoba, and Lake Superior copper in Louisiana.” Charles C Mann, 1491 New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus (New York: Alfred A Knoph, 2005): 25 ↩︎

The term “accidental arrival” is used to combat the long-held narrative of Columbus as an actor of scientific creed; Columbus believed the island of Guanahani (which he named Hispaniola) to be and island to the east of India. See Sai Englert’s Chapter “Accumulate, Accumulate” in Settler Colonialism: an Introduction (Pluto Press, 2022): 32. ↩︎

Census documents are informative but, especially in colonial moments, can also be misleading as Europeans also had biases to report back or exaggerate claims to the crown the number of people they had conquered. Bartolomé de Las Casas, for instance, reported that in 1496 that the area of Hispaniola had about 1,000,000 Indigenous inhabitants. Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo estimated that people living in the Castillo del Oro, or what is now Panama, reached nearly 2,000,000. Information from William Denevan, the Native Population of the Americas in 1492. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. 1992:14. For more on comparisons of colonial census data, see Alan Covey et al, “Dynamics of Indigenous Demographic Fluctuations: Lessons from Sixteenth-Century Cusco, Peru.” Current Anthropology 52, no. 3 (2011): 335–60; Liebmann, Matthew J. et al. “Native American Depopulation, Reforestation, and Fire Regimes in the Southwest United States, 1492–1900 CE.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, no. 6 (2016): E696–704. ↩︎

Massimo Livi Bacci, Conquest: the Destruction of the American Indios. Translated from Italian by Carl Ipsen. Cambridge, UK and Maiden, MA: Polity 2008. ↩︎

Alexander Koch, et al “Earth system impacts of the European arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492”, Quaternary Science Reviews, Volume 207, (2019):13-36. ↩︎

Englert “Accumulate, Accumulate”; See also David Reher “Reflections on the Fate of Indigenous Populations of America” Population and Development Review 37 no. 1 (2011): 172-77. ↩︎

William Denevan “The Pristine Myth”. ↩︎

Mann 1491: pp 129; See also Cook, S.F. and L. B Simpson. 1948. The Population of Central Mexico in the Sixteenth century. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ↩︎

The Triple Alliance refers to a political system whereby the city states of Tenochtitlán, Texcoco, and Tlacopan united to create a system of land distribution and tribute payment. See Jongsoo Lee’s Chapter, “The Aztec Triple Alliance: a colonial transformation of the Prehispanic Political and Tributary System.” Texcoco: Prehispanic and Colonial Perspectives. University Press of Colorado (2014): 63. ↩︎

When Spanish conquistadors encountered the city, many had never seen anything like it. Tenochtitlán was much larger than Paris, at the time Europe’s largest city. They encountered botanical gardens, aqueducts that brought lake water into the city, and hugely ornate temples and streets that were described as immaculate. Mann 1491: 126 ↩︎

For context, the population of England in the 1490s was nearly 1/10 of the size. Mann 1491: 120 ↩︎

See Barbara Mundy “Mapping the Aztec Capital: the 1594 Nuremburg Map of Tenochtitlan, Its Sources and Meanings” Imago Mundi vol 50. (1998):11-33. ↩︎

See Clark Erickson, “The Domesticated Landscapes of the Bolivian Amazon,” in Balée and Erickson eds. 2005. ↩︎

This kind of agro-forestry or “farming with trees” was not easily perceptible to Europeans who had never seen systems like it- many Europeans who encountered people in the Amazon incorrectly stated that they had no agriculture, whereas in reality they had come across a kind of agriculture unlike anything in Europe, Africa, or Asia. Charles C. Mann. 1491:pp 26. ↩︎

Denevan “The Pristine Myth” ↩︎

The interconnectedness of roads such as the Qhapac Nan, or Inka Road, is precisely what created different timelines of colonization’s effects. it is estimated that Inka citizens, for instance, felt the effects of Small pox long before the arrival of Spanish individuals; in a case in which disease can travel faster than people, it is likely that their trading partners to the North had passed it through a series of encounters within a well-defined infrastructure of trade routes. See Jeff Quilter, The Ancient Central Andes [2014] Taylor and Francis 2022. ↩︎

Montenegro et al, “La Situacion Poblacional Peruana: Balance Y Perspectivas” Technical Report Instituto Andino de Estudios en Poblacion y Desarrollo, Lima (1990). ↩︎

Based on the estimations by Henry Dobyns done in 1966, in 1491, the Indigenous population may have reached nearly 112.000.000 people, which at this time would have substantially outnumbered Europe’s population. See Mann. 1491: 94. See also Henry Dobyns “An Appraisal of Techniques with a New Hemispheric Estimate” Current Anthropology. 7 no 4: 1966. ↩︎

![Carta ó Mapa Geográfico de una gran parte del Reino de N. E. [Nueva España], comprendido entre los 19 y 42 grados de latitud Septentrional y entre 249 y 289 grados de longitud del Meridiano de Tenerife, formado de orden del Exc[elentísi]mo S[eño]r B[eilí]o Fr[ey] D[o]n Ant[oni]o Maria Bucarely y Vrsúa p[ar]a indicar la division del Virreinato de México y de las Provincias internas erigidas en Comandancia General en virtud de Reales Órdenes el año 1770](https://dnet8ble6lm7w.cloudfront.net/maps_sm/MEX/MEX0190.png)