Abstract

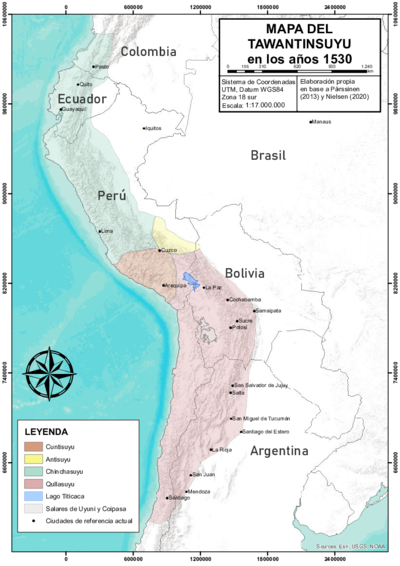

In the process of Spanish conquest and colonization of the Inca State, the indigenous tribute was the first basic tax that the inhabitants of Qullasuyu had to pay as vassals of the king of Spain. Being part of a state society, the “Indians” of the Tawantinsuyu, and particularly the Aymara lordships of the Qullasuyu, produced considerable surpluses and had their own institutions that regulated their transfer. This context was favorable for appropriating these surpluses through an indigenous tribute that, in the first decades, was introduced and presented as tax resembling the Inca tribute, consisting of payments in kind and labor services. However, as Wachtel points out, “while the Inca tribute functioned according to a balanced and circular structure, the Spanish tribute was characterized by its unbalanced and unilateral structure.”1

Since the conquest in the 16th century, the history of indigenous tribute has been long and complex, and extends beyond the colonial period, until the middle or end of the 19th century (this tribute was abolished in Peru in 1854, in Ecuador in 1857, and in Bolivia in 1874). Throughout these three centuries, several modifications were made in relation to the tax amounts, the taxation regime —in kind, in currency, in labor, or in their different combinations—, the taxpayer categories, exceptions, authorities in charge of setting the amounts and collecting the tax, etc. The amendments to the tribute can be understood as responses to the different forms of resistance put up by the Indigenous people, either to evade the tribute or to defend the resources and conditions that enabled their self-sufficiency —or at least, their subsistence.

In the first decades of the conquest and the development of a weak colonial state (1530s - 1560s), some features of the Inca tribute were maintained —out of necessity— (for example, the collective responsibility to make the payment). The amounts were negotiated with the ethnic authorities (kurakas), and the Andean relations and forms of production were respected. Two different stages stand out in the functioning and application of the Indigenous tribute throughout this period: a) a first stage of wars of conquest between 1535 and 1550, and b) a second stage in which the authority of a colonial state still weak and in formation gave its first steps on the road to institutionalization between 1550 and 1569, the year in which important reforms were drafted, which would completely modify the tax regime.2

- Indigenous Tribute in the Process of the Conquest of Qullasuyu 1535 - 1550

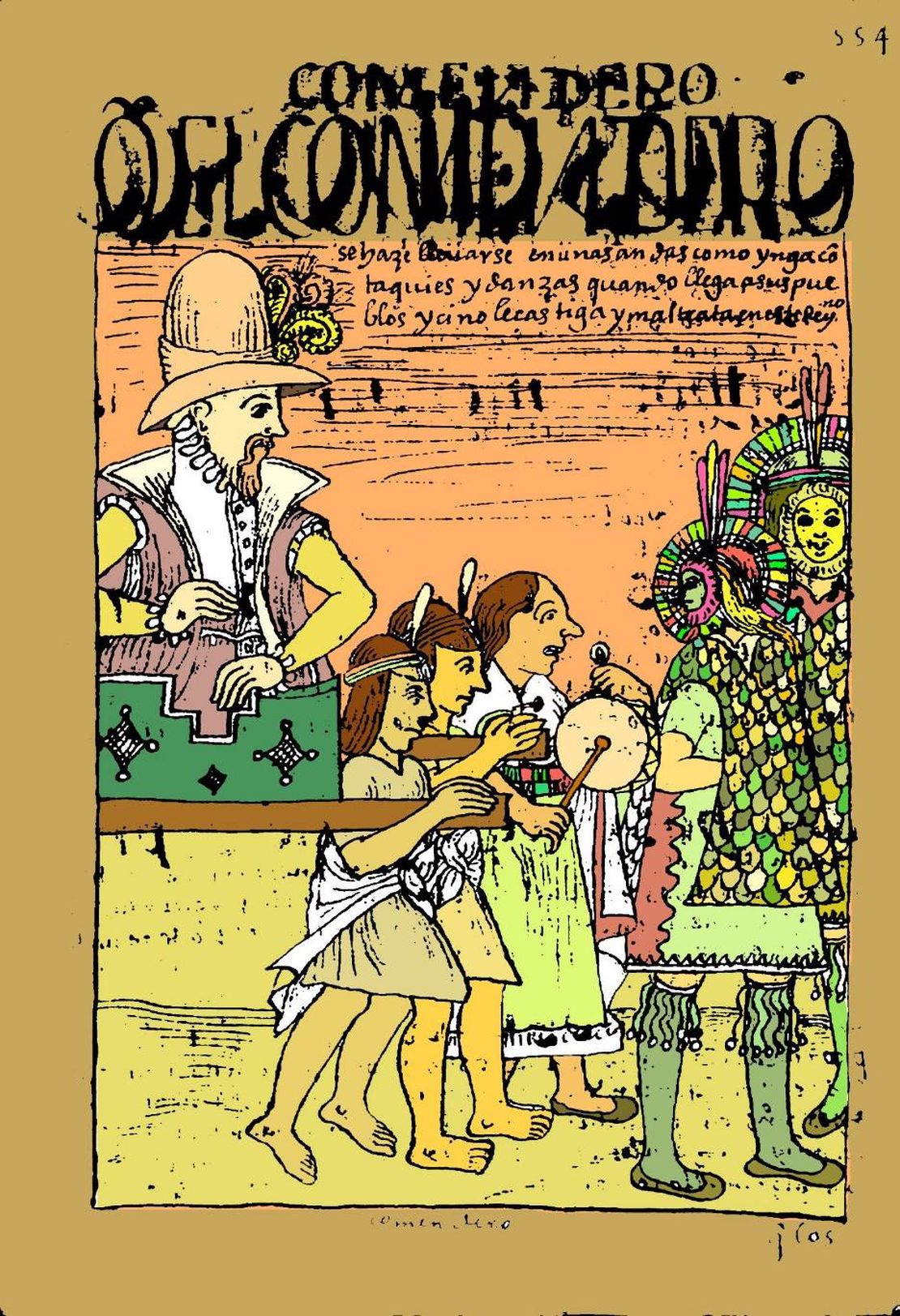

The conquest of Qullasuyu was a stage characterized by chaotic plundering in the context of several internal wars between different factions of Spanish conquistadors and shifting alliances with diverse ethnic authorities and factions of the Inca elite. During this time, the Indigenous populations of the conquered territories were distributed and organized under the rules of the encomienda institution. Although these territories formally belonged to the Spanish crown and their inhabitants had to pay tribute as vassals of the king, the crown relinquished the right to collect tribute from the Indigenous people living in a specifically outlined area to a Spanish subject as a reward for his military contribution to the conquest.

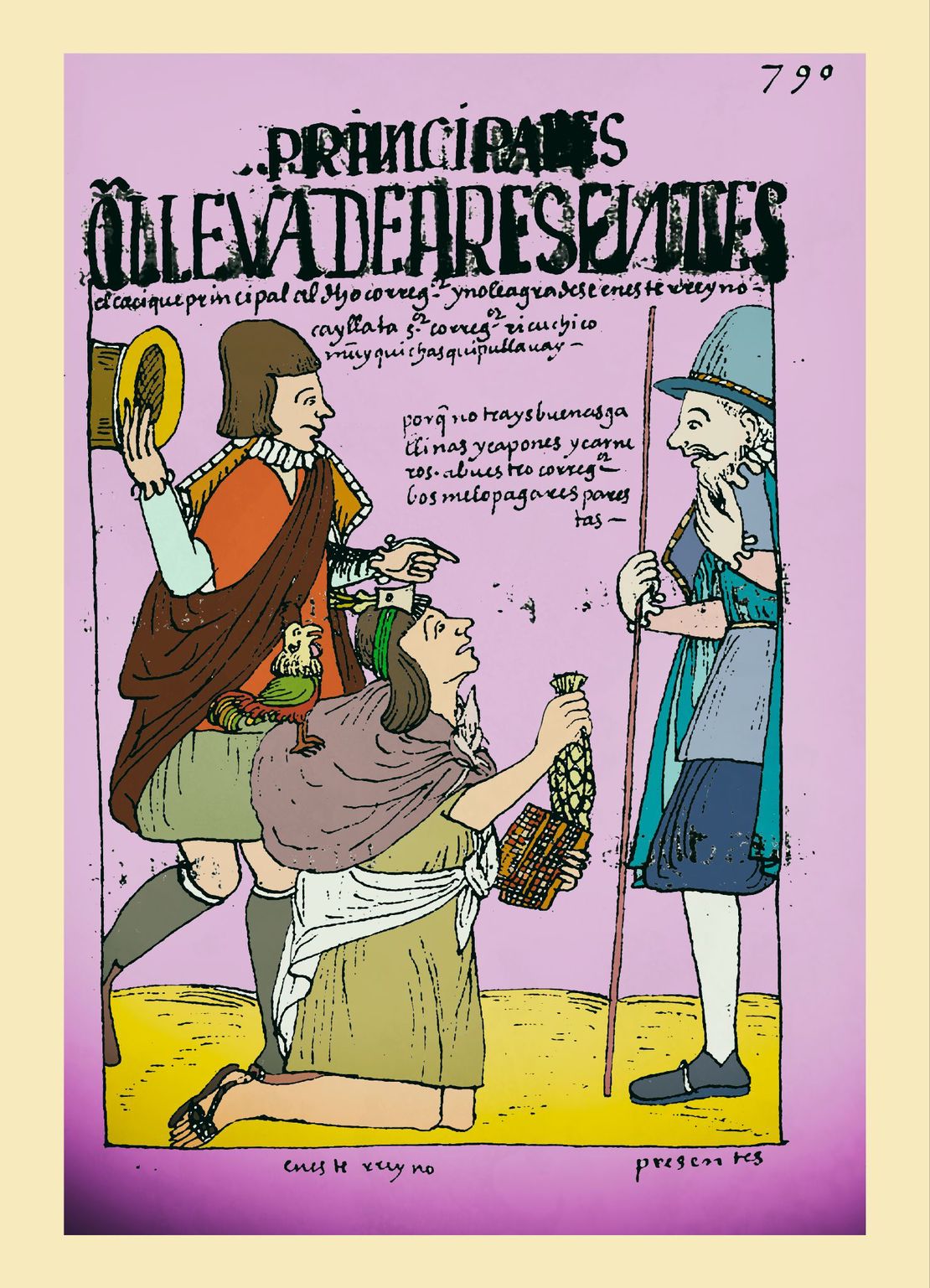

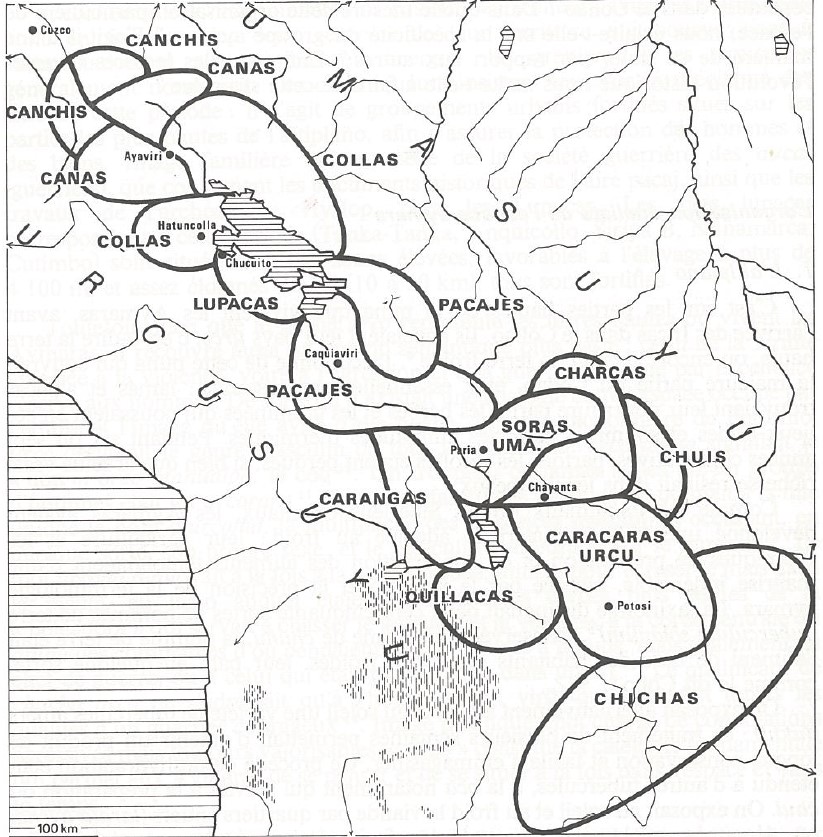

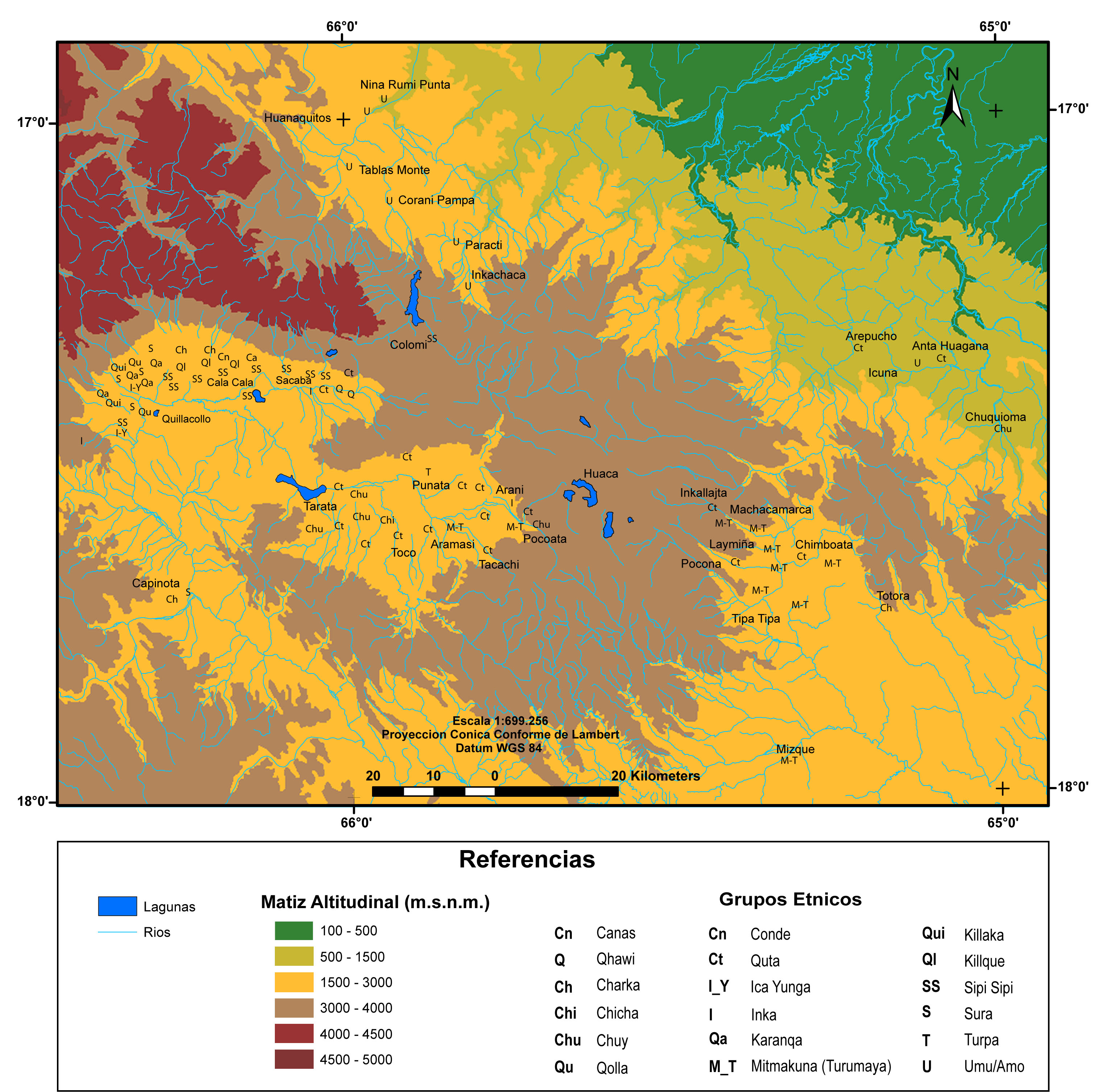

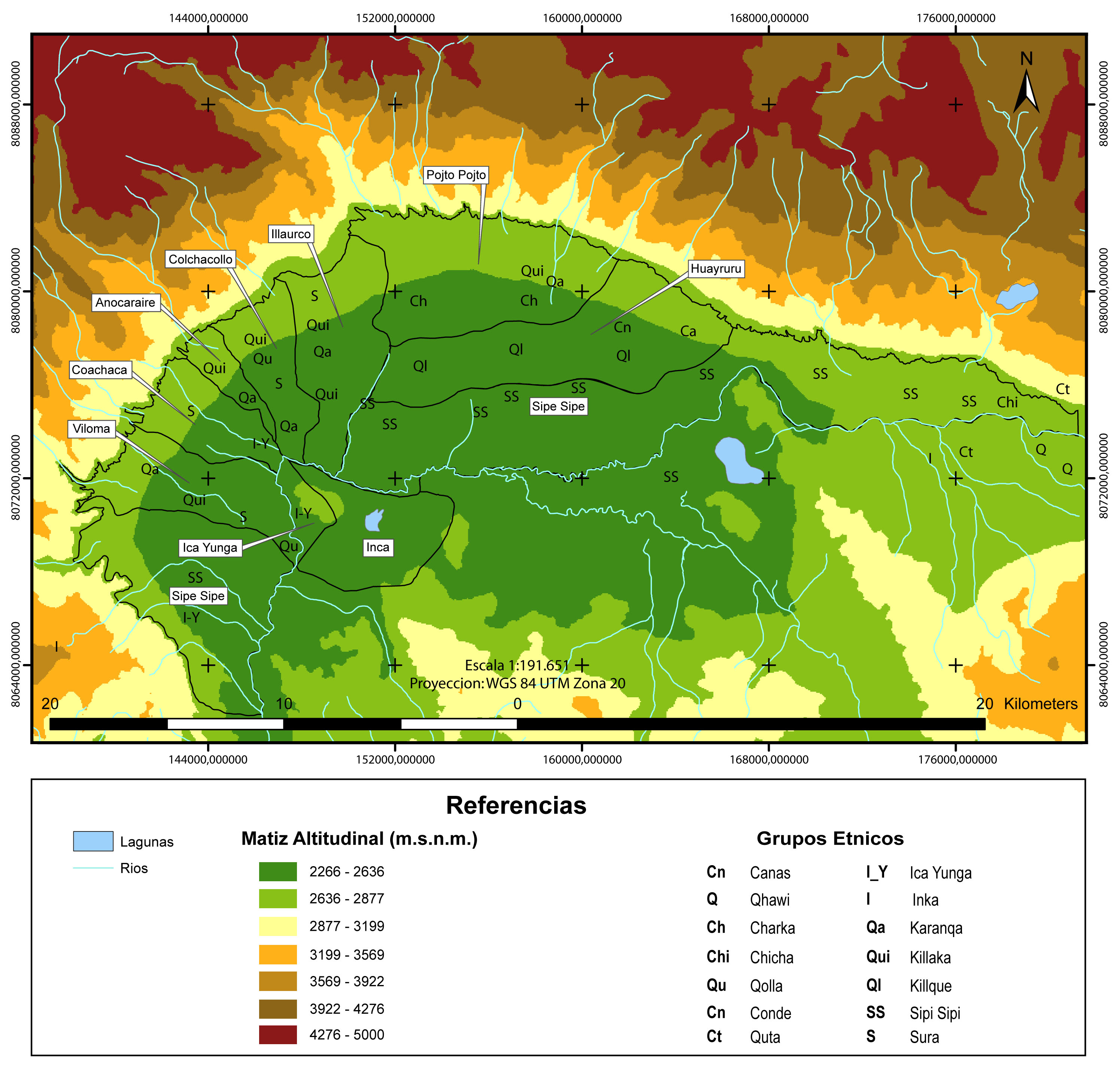

At that time, tribute was paid in kind and labor, and the amounts were negotiated with the ethnic authorities (kurakas or mallkus, called caciques in colonial documents). Situations varied from region to region. In the altiplano, where the main centers (cabeceras) of the Aymara lordships were located and where the Inca state had exercised indirect rule, the conquistadors —now turned into encomenderos— faced powerful kurakas who, in many cases, managed to impose respect for the complex internal organization of their socio-political units and even for the harmony of their territories (including many of their “islands” in the valleys). Conversely, in the Cochabamba valleys, where the multiethnic territories MULTI-ETHNIC TERRITORY under INCA DIRECT RULE: THE LOWER VALLEY OF COCHABAMBA in the 1530s had been organized and governed directly (direct rule) by the Inca state, the encomenderos had greater power since the Kurakas —upon the fall of the Inca state— depended on them to exercise their authority over the Indigenous taxpayers.

- Indigenous Tribute: First Attempts at Regularization, 1550 - 1570

Although the Viceroyalty of Peru was created in 1542 —its jurisdiction included the Tawantinsuyu territory and, therefore, the Qullasuyu—, it was not until the end of the internal wars that the colonial state could make its early attempts at order and institutionalization. Thus, in 1550, the first Indigenous tribute tax was levied. Colonial authorities conducted a tax census that allowed them to estimate the productive potential of each zone, defining the amounts of tribute per animal, agricultural, and manufactured products. In an effort to control the power of the encomenderos —and thus avoid the consolidation of local powers that would threaten the crown´s authority—, there was an attempt to suspend the personal service of the Indians and limit the duration of encomiendas, but —in practice— the progress was minimal. It was possible though to undermine the power that some kurakas had exerted until then to negotiate the tribute amounts.

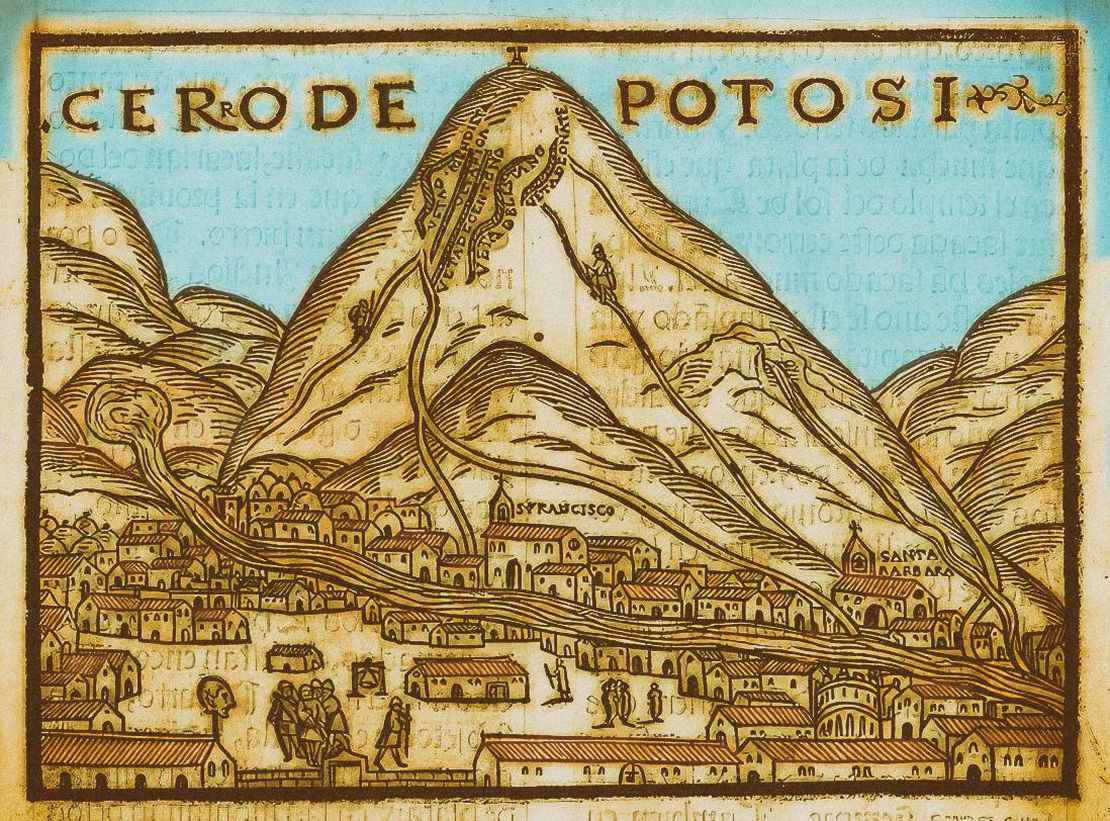

These features of Indigenous tribute during the first three decades of Spanish conquest and colonization were radically modified in the framework of the major reforms implemented by Viceroy Toledo starting in the 1570s. Tribute was then defined as an individual tax to be paid in currency, and labor services were regulated in a system managed by the colonial state. This system, known as the mita, consisted of the mandatory recruitment of Indigenous labor force mainly for the mines of Potosí. From then on, the increasing monetization of Indigenous tribute contributed to the progressive integration of the Indigenous people into the market, the fragmentation of the Aymara lordships, and the erosion of their material conditions for reproduction.

Bibliography

Larson, Brooke. Colonialism and Agrarian Transformation in Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990. La Paz: Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2017.

López-Beltran, Clara. Economic Structure of a Colonial Society. Charcas en el Siglo XVII. La Paz: Centro de Estudios de la Realidad Económica y Social, 1988.

Platt, Tristan. “On the Pre-Toledan Tax System in Upper Peru.” Advances 1, (1978): 33-46.

Sánchez Albornoz, Nicolás. Indians and Tributes in Upper Peru. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1978.

Spalding, Karen. Huarochirí. An Andean Society Under Inca and Spanish Rule. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1984.

Wachtel, Nathan. Sociedad e Ideología. Ensayos de Historia y Antropología Andinas. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1973.

Estudios Peruanos, 1973), 124.

](/images/content/TL002Tributo/image1_huf5e31d019bde78eaa0ee0b927ac55add_478105_1110x0_resize_q80_lanczos.jpg)