Abstract

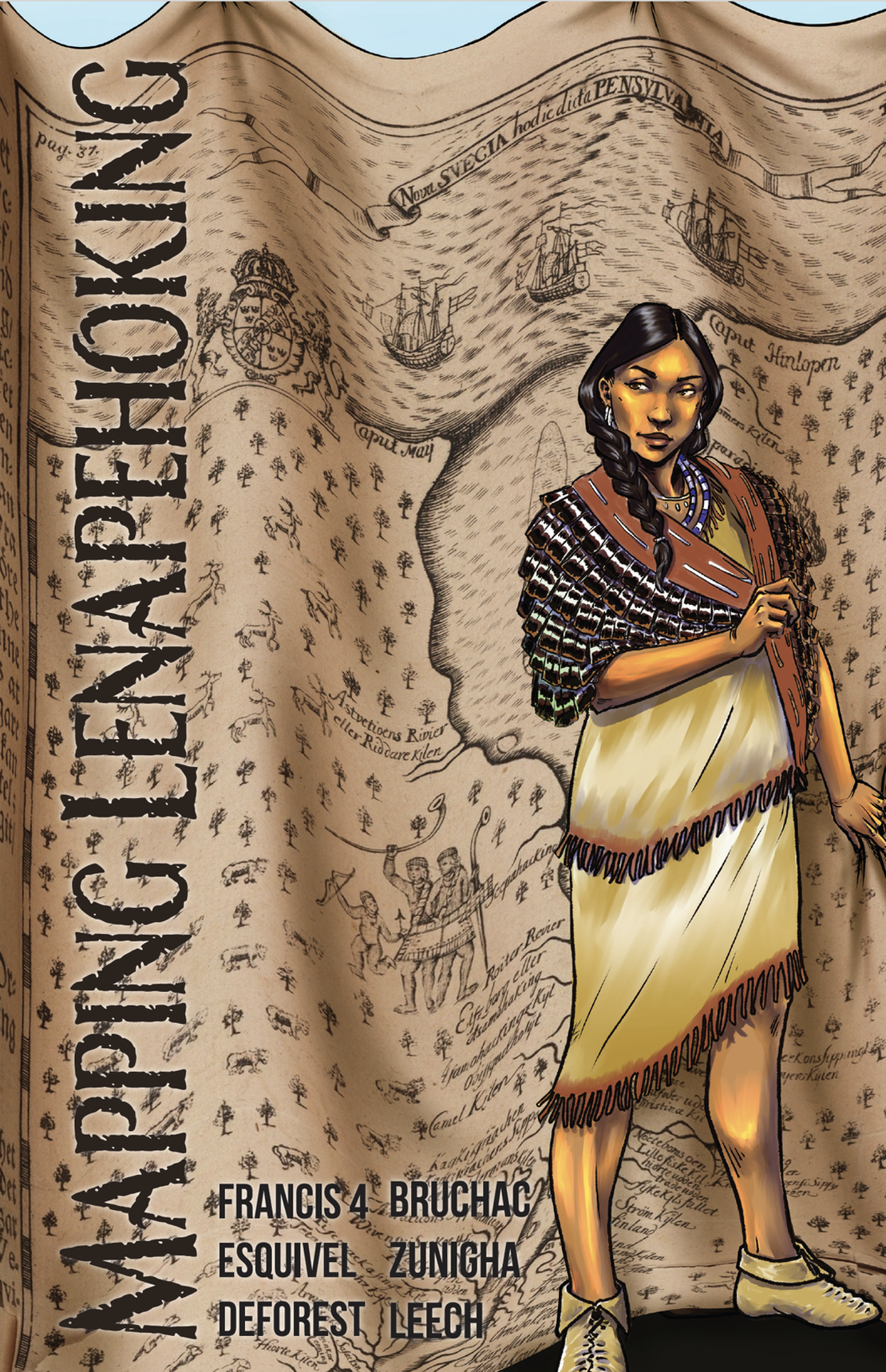

The colonial narrative of settling Lenapehoking, in the region now known as Pennsylvania, has been characterized according to a mythical ideal of a peaceful colonization without conquest, commonly attributed to the pacifist ideology of the Quakers. The remarkable lack of direct violence in the region was not, however, due to William Penn’s influence; it was a product of distinctive Lenape values that encouraged peaceful conflict resolution. The Lenape believed that different peoples were given differing lands to live on, and differing religious beliefs, to maintain proper balance and harmony. Yet, despite Lenape efforts, Penn’s settlers brought European diseases, trade goods, agricultural practices, cultural assumptions, and institutions that violently re-shaped the Lenape world. By revisiting these histories, and reconsidering the persistence of Lenape values in the social memory of the land, we can radically reimagine our past and present relationality. Lenape principles of reciprocity reflect a decolonial mode of relating that can also center Indigenous futurity in our collective political imagination.

Reciprocity and Reciprocal Liberty

Reciprocity was crucial to sustaining Lenape culture, reflected in the ideal of “reciprocal liberty”—a kind of liberty that “fostered personal freedom for both one’s self and others.1 This is clear in the material record: archaeological studies of pre-colonial Lenape burial sites show little evidence of violent death, and their towns were unfortified, indicating their primarily peaceful coexistence with neighboring tribes.2 Lenape communities were typically composed of small bands; in the absence of centralized governance, independent Lenape groups formed reciprocal diplomatic and military alliances with one another and with others (including colonial settlers), as needed.3

A cornerstone of Lenape diplomacy was peace-making, turning to violence or the threat of violence only when peaceful efforts failed.4 Reciprocal liberty is also reflected in the egalitarian and democratic socio-political structure of Lenape society. Sachems made decisions informed by an elders’ council, and nothing was done impulsively without consulting both the council and community members. Sachems governed and held power through the collective will of their people. William Penn remarked: “Tis admirable to consider, how Powerful the Kings are, and yet how they move by the Breath of their People.”5 Although women did not hold or inherit leadership positions, the succession of male sachems passed to a King’s brother, or to the sons of his sister, reflecting the importance of matrilineal descent in Lenape society.6

The First Treaty Tribe

The Lenape have a reputation as the “first treaty tribe,” earned not just through their treaties with William Penn, but also through the 1778 Treaty of Fort Pitt, the first Indigenous treaty to be negotiated with the newly-established United States government.7 The Lenape are also notable for having negotiated an earlier treaty with the Haudenosaunee (then called the Five Nations Iroquois). That 1669 “Great Peace” treaty was the first in a long series of inter-Indigenous treaties mediated by the Lenape across the Eastern Woodlands.8 By accepting the protection (and the controversial socio-political status of “women”) offered by the Haudenosaunee, the Lenape joined in the “Covenant Chain” alliance with English settlers in New York colony.9 Oral and historical traditions, as recorded by both Moravian and Mohawk observers, testify that this peace was established in the aftermath of (and likely as a response to) colonial settlement.10

Lenape patterns of peaceful interaction with Dutch and Swedish “old settlers” facilitated trade while deterring conflict; the success of those early settlements laid the groundwork for the subsequent English colony. For most of the 1600s, despite the steady influx of colonial settlers, Lenape people maintained control of the Lenapewhittuck (Delaware River) valley region through “superior numbers, strategic use of violence and the threat of violence, and emphasis on peace and freedom.”11 Yet, by the mid-1600s, the introduction of diseases led to high mortality rates for the Lenape (and other Indigenous peoples) who had minimal immunities to European pathogens; these losses had profound moral and spiritual effects.12

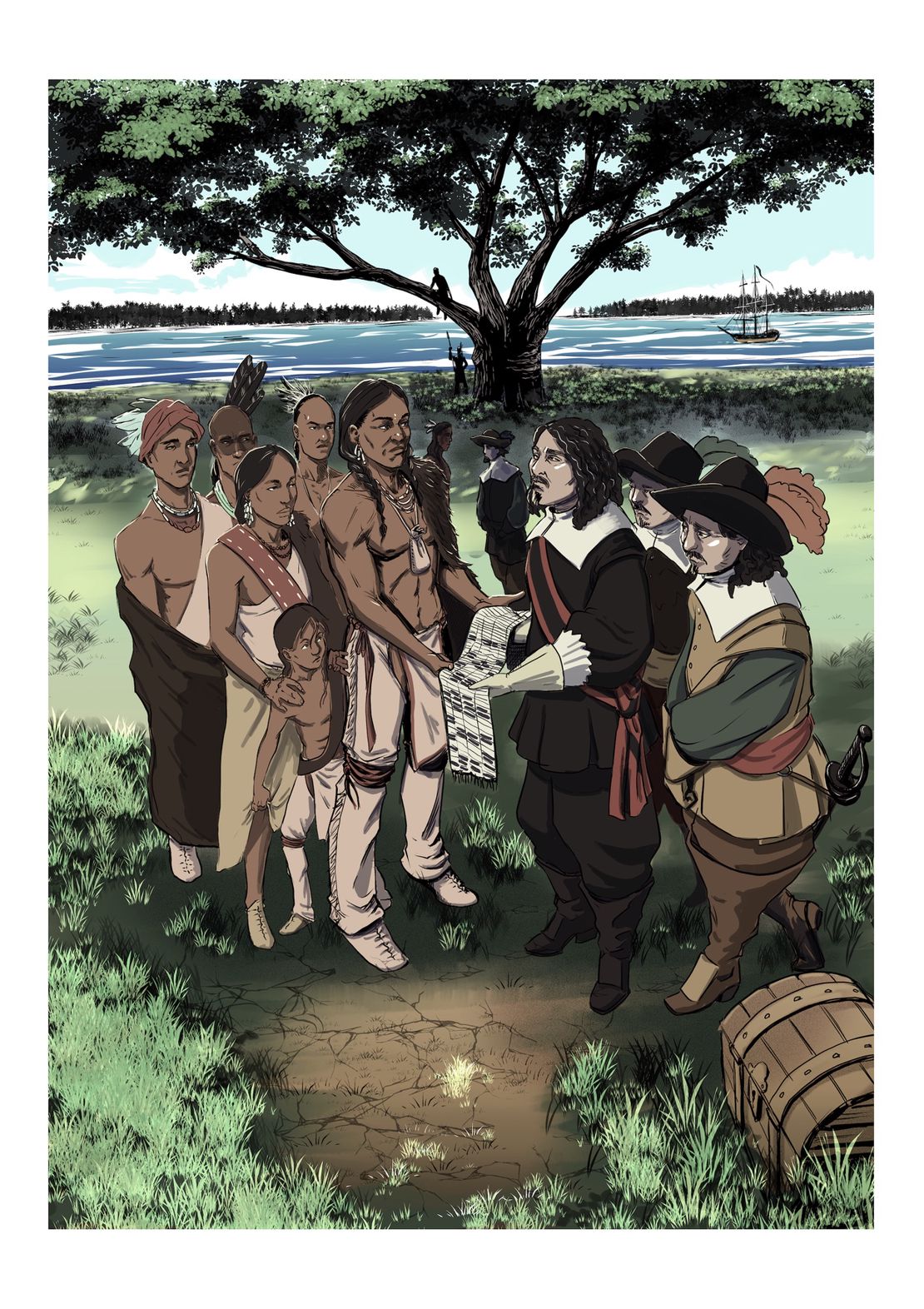

Land Transactions & Strategic Diplomacy

The principles of reciprocity that underpinned Lenape protocols of treaty-making and trade were visible in land transactions that involved both diplomatic and economic exchanges. For the Lenape, these encounters fit into a broader network of relationality; the exchange of ceremonial gifts (e.g., wampum, furs, trade goods) symbolized new reciprocal inter-cultural relations, rather than simple payments. Differing views of these transactions led to conflict, when colonial officials refused Lenape demands for “repeat payments” and “confirmatory” treaties for land that, according to European traditions, had already been “sold.”13 Lenape people also expected to retain hunting, fishing, farming, and habitation rights on lands that were collectively rather than individually held. There was no separation between the people and the land, expressed by Lenape cultural historian Curtis Zunigha as: “We do not own the land, we are of the land, we belong to it.”14

This distinction illustrates the importance of standpoint in understanding colonial history. As legal historian Steven Newcomb explains it:

“We are able to reflect upon two main perspectives: the viewpoint of our Native ancestors, standing on the shore looking at an invasive ship sailing toward them, and the viewpoint of the Christian European colonizers, standing on the deck of the ship, looking at our ancestors. This contrast enables us to consider the difference between the mental world of our ancestors, created by means of our own languages, and the mental world of the Christian Europeans created by means of their languages. From this starting point we are able to express a view-from-the-shore perspective and a view-from-the-ship perspective.”15

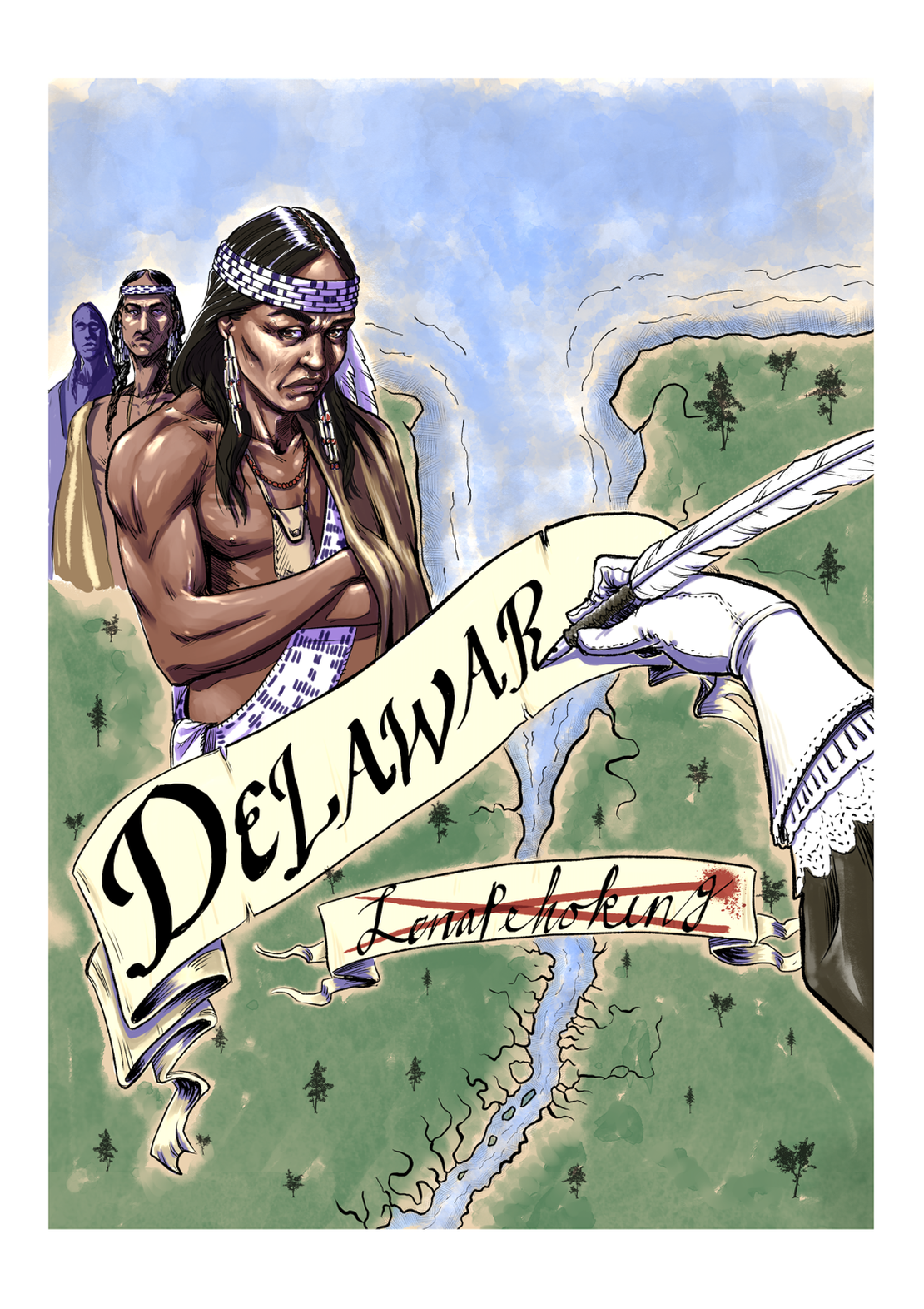

To understand the “view from the shore,” it is essential to visualize the dispossession of Lenapehoking as not just the transfer of land as property, but the transformation of land into property. Here, as elsewhere on the continent, European possession was enacted by generating “conditions that require divestment and alienation from those who appear, only retroactively, as its original owners.”16 Dispossession, in effect, re-coded the land from the framework of Lenape reciprocal relations to one of colonial commercial relations.

Lenape leaders refused to sell large parcels of land, but they were willing to permit small settlements, while anticipating the option to renegotiate agreements for any unsettled lands. In the 1680s, in the spirit of establishing peaceful relations (as they had with the Dutch and Swedish), the Lenape offered Penn’s English colonists free passage through Lenape lands; they also agreed to warn their new neighbors about threats from other Natives.17 A 1682 treaty, negotiated by William Markham with sixteen Lenape Sachems, also established judicial equity, stipulating: “that if English or Indian should at any time abuse one another, complaint might be made to their respective government, and that satisfaction may be made according to the offence.”18 By enforcing equal treatment and encouraging peace, the Lenape tutored European settlers about the terms under which they would be allowed to remain in Lenapehoking.19

Reciprocity in Freedom and in Violence

William Penn recognized Lenape proficiency in strategic diplomacy, noting that they could not be outwitted in any treaty. He was particularly impressed by Lenape generosity, observing the free circulation of wealth and resources. At festivals and common meals, just as in treaty-making, Sachems were charged with the distribution of gifts and food, serving themselves last. Intra-tribal conflicts were rare, and easily forgiven. In cases of serious wrongdoing, Lenape justice demanded that the guilty party atone through “Feasts and Presents of their Wampum, which is proportioned to the quality of the Offence or Person injured.”20

Lenape principles of reciprocity extended even to situations of cross-cultural conflict, as exemplified in the story of Frances Slocum, a Quaker girl captured in 1778 and raised by the Lenape.21 From the Lenape standpoint, the Slocums (typically portrayed as kindly pacifists) were not innocents; they were “part of the massive influx of settlers” invested in violently reshaping the territory. Frances’ brother, Giles, had participated in a previous colonial raid that destroyed a Lenape village, burning homes with families inside them.22 The Lenape response was targeted and proportional, grounded in the desire to partially restore balance to the village that was burned. The captured girl, Frances Slocum, was renamed Weletawash and adopted by a family that had lost their daughter. This practice, similar to that of Haudenosaunee “mourning wars,” had the goal of restoring reciprocal relations, even in the midst of violence.23

Lenape beliefs in personal freedom sometimes influenced European values. For example, although Quaker settlers professed respect for individual and religious freedom, they nonetheless embraced the importation of enslaved people from Africa, the West Indies, and Southeastern tribal nations. Lenape people, who were firmly opposed to this practice, offered refuge to escaped Africans, and demanded an end to all slave trading. In response, several attempts were made by colonial leaders to end the practice, including prohibitive duties on imports of enslaved people. The Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of Friends finally weighed in, deciding in 1719 “that Friends do not buy or sell Indian slaves.”24

Even so, peaceful relations faded. For seven decades living alongside English colonists, from the 1680s into the 1750s, Lenape leaders had continually advocated for reciprocal liberty for the benefit of all. But the duplicity of Penn’s settlers – most evident in the infamous 1737 “Walking Purchase” that alienated 1200 square miles of land – made it clear that the Pennsylvania colonists could not be trusted.25 This breakdown in relations led to decades of violence and forced relocations.

The Spiritual Basis for Reciprocity

For generations, Lenape people had practiced the Gamwing (Big House Rite), an annual ritual that reinforced community identity, harmony, and gender relations. Celebrated after the fall harvest, the ceremony evoked responsibility (embodied by a river, clan, town, and chief) and revelation (embodied by a person, spirit, place, and access to power), by recreating the universe according to the Lenape origin story.26 For twelve days, during each ceremony, people gathered in a building that reflected Lenape concepts through “the oval outline as the turtle’s back on the floor and the center post as the world tree. . .anchored by Creator, cosmos, and creations.”27 Within the bounds of the Big House, Lenape practitioners ritually reinforced and conceptually rebuilt balance among kin and community.

By the late 1700s, as it became increasingly difficult for Lenape people to live in Lenapehoking, families began relocating westward. Although Pennsylvania was situated in Lenape homelands, the region was considered dangerous according to the concept of kwulakan, the idea “that an area in which harmony had broken down could not be entered into without invoking the wrath of the deities.”28 And so, up into the 1860s, in a series of relocations from Pennsylvania, to Ohio, to Oklahoma, and other locales, Lenape families carried their kin and culture westward, for the sake of survivance. As they did so, they continually rebuilt the Lenape universe through long-standing reciprocal practices and rituals, including new Big Houses and new Gamwings, in each of their new home places.29

References Cited:

Bryce, Douglas W., ed. 1973. “A Glimpse of Iroquois Culture through the Eyes of Joseph Brant and John Norton.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 117 (4) (August 1973): 286-294.

Dunn, Mary Maples and Richard S. Dunn et al., eds. 1981-1987. The Papers of William Penn. Five volumes. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Fischer, David Hackett. 1989. Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fur, Gunlög. 2011. A Nation of Women: Gender and Colonial Encounters Among the Delaware Indians. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Glassburn, Ashley. 2019. “Settler Standpoints.” The William and Mary Quarterly 76: 3: 399-406.

Haefeli, Evan. 2023. “The Great Haudenosaunee-Lenape Peace of 1669: Oral Traditions, Colonial Records, and the Origin of the Delaware’s Status as ‘Women.’” New York History 104 (1): 79-95.

Hale, Duane Kendall Hale. 1984. Turtle Tales: Oral Traditions of the Delaware Tribe of Western Oklahoma. Anadarko, OK: Delaware Tribe of Western Oklahoma Press.

Heckewelder, John. 1821. “Answers to Queries respecting Indian Tribes,” in “Communications made to the Historical and Literary Committee & to Members of the American Philosophical Society, on the Subject of the History, Manners & Languages of the American Indians.” Mss.970.1H35c. American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, PA.

Jennings, Francis. 1974. “The Delaware Indians in the Covenant Chain.” In A Delaware Indian Symposium. Anthropological Series No. 4, edited by Herbert C. Kraft, 89-101. Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. https://archive.org/details/delawareindiansy00unse/page/n9/mode/2up?q=prehistory

Kraft, Herbert C. 1974. “Indian Prehistory of New Jersey.” In A Delaware Indian Symposium. Anthropological Series No. 4, edited by Herbert C. Kraft, 1-56. Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. https://archive.org/details/delawareindiansy00unse/page/n9/mode/2up?q=prehistory

Meginness, John F. 1891. Biography of Frances Slocum, the Lost Sister of Wyoming. A Complete Narrative of Her Captivity and Wanderings Among the Indians. Williamsport, PA: Heller Bros.’ Printing House.

Miller, Jay. 1997. “Old Religion Among the Delawares: The Gamwing (Big House Rite).” Ethnohistory 44 (1): 113:-134.

Miller, Jay. 1975. “Kwulakan: The Delaware Side of their Movement West.” Pennsylvania Archaeologist 45 (4): 45-46.

Myers, Albert Cook, ed. 1937. William Penn’s Own Account of the Lenni Lenape or Delaware Indians. Moylan, PA: Albert Cook Meyers. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32435011069713&seq=11

Nichols, Robert. 2018. “Theft Is Property! The Recursive Logic of Dispossession.” Political Theory 46 (1) (February 2018): 3-28

Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission. no date. “The Walking Purchase – August 25, 1737.” Original document and transcript published in the Pennsylvania Archives, First Series Vol. 1: 541-543. http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/portal/communities/documents/1681-1776/walking-purchase.html

Richter, Daniel K. 1983. “War and Culture: The Iroquois Experience.” William and Mary Quarterly 40 (1983): 528-559.

Soderlund, Jean R. 2019. “The Lenape Origins of Delaware Valley Peace and Freedom.” In Quakers and Native Americans, edited by Ignacio Gallup-Diaz and Geoffrey Plank, 15-29. Leiden, Boston: Brill.

Soderlund, Jean R. 2015. Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society Before William Penn. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Soderlund, Jean R. 1985. Quakers and Slavery: A Divided Spirit. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sugrue, Thomas J. 1992. “The Peopling and Depeopling of Early Pennsylvania: Indians and Colonists, 1680-1720.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 116 (1): 3-31.

Jean R. Soderlund, “The Lenape Origins of Delaware Valley Peace and Freedom,” in Quakers and Native Americans, edited by Ignacio Gallup-Diaz and Geoffrey Plank (Leiden, Boston: Brill 2019): 16. On “reciprocal liberty,” see David Hackett Fischer, Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 595. ↩︎

Herbert C. Kraft, “Indian Prehistory of New Jersey,” in Herbert C. Kraft, ed., A Delaware Indian Symposium, Anthropological Series No. 4 (Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission 1974), 38. ↩︎

Soderlund, “The Lenape Origins of Delaware Valley Peace and Freedom,” 18. Also see Gunlög Fur, A Nation of Women: Gender and Colonial Encounters Among the Delaware Indians (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011). ↩︎

Soderlund, “The Lenape Origins of Delaware Valley Peace and Freedom,” 19. ↩︎

Albert Cook Myers, ed., William Penn’s Own Account of the Lenni Lenape or Delaware Indians (Moylan, PA: Albert Cook Meyers 1937), 40-41. ↩︎

Myers, ed., William Penn’s Own Account of the Lenni Lenape,” 39. ↩︎

Evan Haefeli, “The Great Haudenosaunee-Lenape Peace of 1669: Oral Traditions, Colonial Records, and the Origin of the Delaware’s Status as ‘Women’,” New York History 104 (1) (2023): 79-95. For the reference to Lenape as the “first treaty tribe,” see Duane Kendall Hale, Turtle Tales: Oral Traditions of the Delaware Tribe of Western Oklahoma (Anadarko, OK: Delaware Tribe of Western Oklahoma Press 1984), 3, 45. ↩︎

Haefeli, “The Great Haudenosaunee-Lenape Peace of 1669,” 82. ↩︎

Francis Jennings, “The Delaware Indians in the Covenant Chain,” in A Delaware Indian Symposium, Herbert Kraft, ed. (Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission 1974): 89-101. ↩︎

Haefeli, “The Great Haudenosaunee-Lenape Peace of 1669,” 85-86. Moravian sources include John Heckewelder, “Answers to Queries respecting Indian Tribes,” in “Communications made to the Historical and Literary Committee & to Members of the American Philosophical Society, on the Subject of the History, Manners & Languages of the American Indians” (1821), Mss.970.1H35c, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, PA. For Mohawk sources, see Douglas W. Bryce, ed., “A Glimpse of Iroquois Culture through the Eyes of Joseph Brant and John Norton,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 117 (4) (August 1973): 286-294. ↩︎

Soderlund, “The Lenape Origins of Delaware Valley Peace and Freedom,” 15. ↩︎

Thomas Sugrue, “The Peopling and Depeopling of Early Pennsylvania: Indians and Colonists, 1680-1720,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 116 (1) (1992), 11. ↩︎

Sugrue, “The Peopling and Depeopling of Early Pennsylvania,” 22. ↩︎

Curtis Zunigha, interview by Safaya Smallwood, November 12, 2023. ↩︎

Steven Newcomb, “Johnson v. M’Intosh and the Missing Cover of the Jigsaw Puzzle,” Canopy Forum: On the Interactions of Law & Religion, April 13, 2023. ↩︎

Robert Nichols, “Theft Is Property! The Recursive Logic of Dispossession,” Political Theory 46 (1) (February 2018), 3. ↩︎

Soderlund, “The Lenape Origins of Delaware Valley Peace and Freedom,” 17. ↩︎

Markham, William Penn’s cousin, was governor of the Pennsylvania Colony when he transacted this treaty in the summer of 1682, several months before Penn’s fall 1682 treaty at Shackamaxon. Mary Maples Dunn and Richard S. Dunn et al., eds. The Papers of William Penn (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press 1981-1987), 2: 261-269. ↩︎

Soderlund, “The Lenape Origins of Delaware Valley Peace and Freedom,” 28. ↩︎

Myers, ed., William Penn’s Own Account of the Lenni Lenape,” 33, 43. ↩︎

John F. Meginness, Biography of Frances Slocum, the Lost Sister of Wyoming. A Complete Narrative of Her Captivity and Wanderings Among the Indians (Williamsport, PA: Heller Bros.’ Printing House 1891). ↩︎

Ashley Glassburn, “Settler Standpoints,” The William and Mary Quarterly 76: 3 (2019), 402. ↩︎

Glassburn, “Settler Standpoints,” 403. For fuller discussion of the Haudenosaunee practice of “mourning wars,” see Daniel K. Richter, “War and Culture: The Iroquois Experience,” William and Mary Quarterly 3rd series 40 (1983): 528. ↩︎

Jean R. Soderlund, Quakers and Slavery: A Divided Spirit (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press 1985), 21, 42, 166. ↩︎

“The Walking Purchase – August 25, 1737,” Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission, original document and transcript published in the Pennsylvania Archives, First Series Vol. 1: 541-543. ↩︎

Jay Miller, “Old Religion among the Delawares: The Gamwing (Big House Rite),” Ethnohistory 44 (1) (Winter 1997): 113-134. ↩︎

Miller, “Old Religion Among the Delawares,” 127. ↩︎

Jay Miller, “Kwulakan: The Delaware Side of their Movement West,” Pennsylvania Archaeologist 45 (4) (1975): 45-46. ↩︎

Miller, “Old Religion Among the Delawares,” 114. ↩︎