Abstract

The map has the capacity to define what one wants to bring into existence as a formal and political constitution. In this specific location, being on the map or disappearing from it depicts the prevailing power relations and the material and symbolic conflicts. As of our experience with Indigenous peoples and quilombola communities in Itacuruba, northeastern Brazil, we aim at highlighting how collective struggles shape the repertoire of confrontations with the State´s development policy, which in turn contrasts with the presence of social agents in their territories.

The debate on whether or not to be on the map, or even to disappear from it, has been —we dare say—, the main guiding thread of the actions and discussions held at the heart of the Projeto Nova Cartografia Social in the Pernambuco center*,* which since 2006 systematizes experiences of auto-mapping of traditional peoples and communities in northeastern Brazil.1 The map, which can take on a different nature, has the capacity to define what one wants to bring into existence as a formally and politically constituted entity or being. It is offered as an instrument to recognize the presence and existence of something or someone, in a certain physical and geographical area. Being on the map —in this location—, evinces symbolic power relations, territorial and —more specifically here as part of our interest— political confrontations.

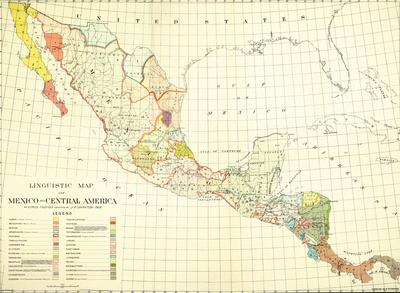

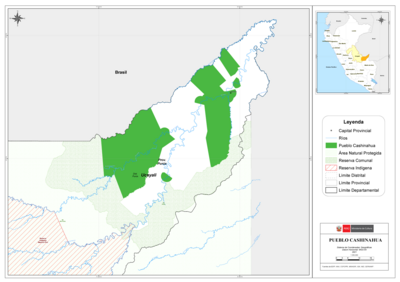

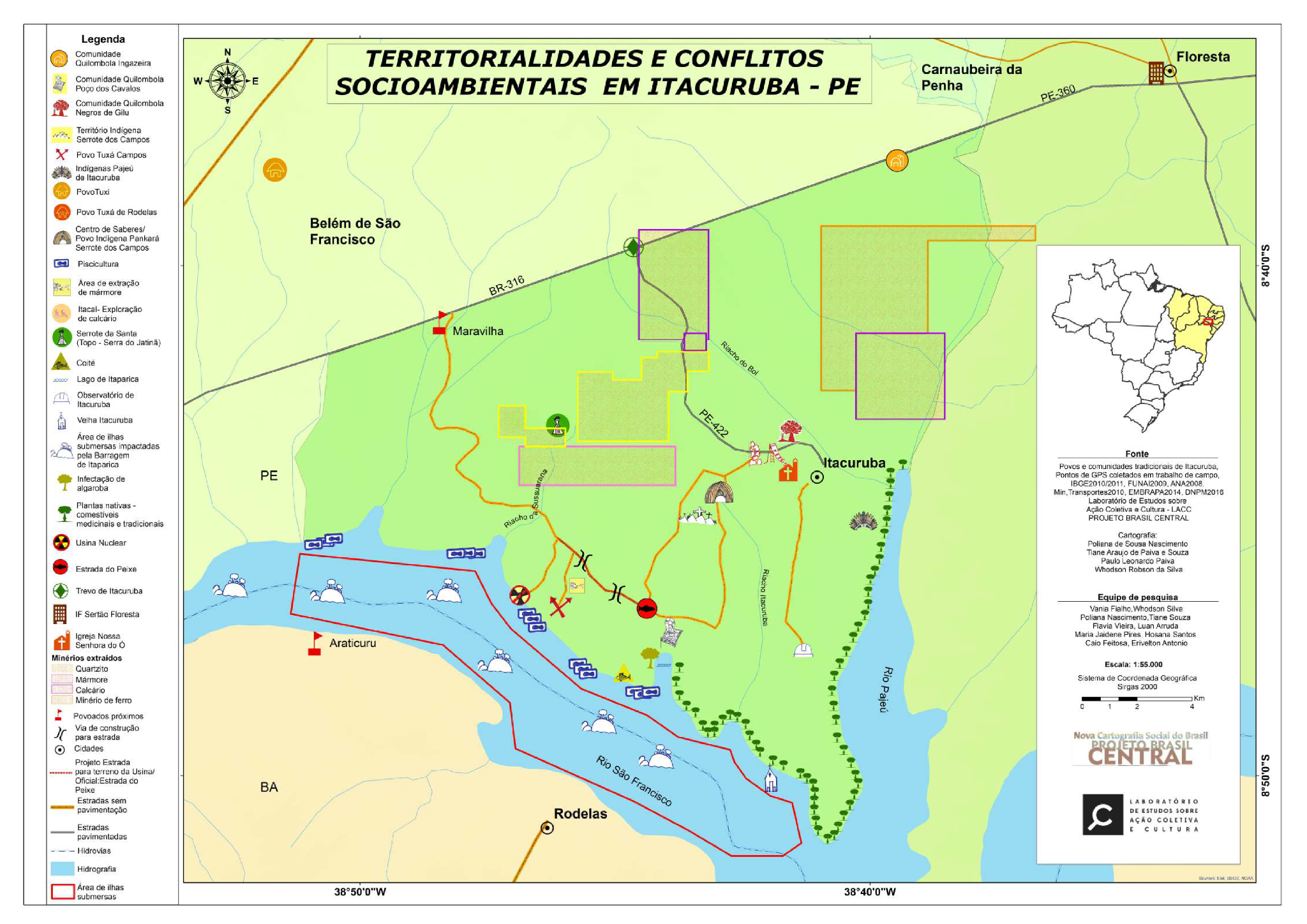

A recent experience, started in 2015, delved us into the specific features of power games and socio-spatial dynamics in the construction of cartographic representations of the municipality of Itacuruba, in the Sertão de Itaparica. Initially, at the request of the local indigenous and quilombola communities themselves, we traced the trajectories and research relationships that made the drafting of the map possible: “Territorialities and socio-environmental conflicts in Itacuruba” —published in 2019 along with the Newsletter, “We resist to exist: we say no to the nuclear power plant in São Francisco”, which is also part of it. As revealed in the map´s title, Indigenous and quilombolas sought to map and thus be able to denounce the socio-environmental conflicts in the area, conflicts anchored in historical relations of environmental expropriation and violations of collective rights by large energy and mining projects.2

Source: Projeto Nova Cartografía Social (2019)

In the “small stone,” as per its translation from Tupi, an estimated 5,000 inhabitants participate in the dynamism of the smallest municipality in the province of Pernambuco. Apparently, this is a city without motorcycles, without cars, a slow city, as they say in the newspapers and in the government blueprints that conveniently depict this for everyone to believe in the emptiness and opacity of a sertão that is crystallized in the image of a mandacaru or a dead cow. A dry and impoverished region, without any prospects of development or happiness, where the convinced and determined “planners” mobilize representations that, while justifying the so-called infrastructure works, create synoptic realities on the ecological and, therefore, also on the living spaces of traditional peoples and communities.

A fateful example of the materialization of these disputes was the possibility of Itacuruba disappearing from the map. A proposal for change in the Federal Pact, which at the time was addressed in ongoing discussions about the map under construction, suggested that municipalities with less than 5,000 inhabitants and revenue collection amounting to less than 10% of total revenues be absorbed and incorporated by other neighboring municipalities; in the specific case of Itacuruba, by Floresta or Belém do São Francisco. The stone, considered small, would suddenly disappear from the map due to an innovative design in the distribution of resources and duties among the Union, the provinces, and the municipalities, standing as the main axis of transformation of the Brazilian economy as of 2019. In the broader process of commissioning large projects in Itacuruba, this is presented as one of the tactics to blur local realities and hinder access to the project´s decision-making spaces, as reported by indigenous people and quilombolas in the map construction workshops:

What we find most striking of all is that when we were able to open the map that those individuals had drafted [the Northeast Nuclear Power Plant project], it was possible to see how they represented our municipality. The map they had drafted had no traces of human beings —as if no one inhabited those territories, as if it were a desert— so if the power plant construction were not accepted, everything would boil down to that: a desert, filth, barren land! (Lucélia Leal, Pankará Serrote de los Campos Indigenous people).

They do not want to build [the Northeast Nuclear Power Plant] in another municipality because the investment is much higher, more people must be displaced; it is different if it is built here, as they stated: ‘Nobody will leave their place’. It is basically that concept of the 4,000 souls, as they mentioned in the newspaper and as they themselves state: ‘Itacuruba is the best area because it is an empty region, we are little over 4 thousand souls here, few to displace, and, if by any chance they all die, they will need fewer coffins.’ [Emphasis added]. (Valdeci Ana, quilombola Poço dos Cavalos community*)*

As a response to the intentional production of empty territories, the map drafted by Indigenous and quilombolas of Itacuruba traces and evinces the active network of relationships that shape the socio-cultural dynamics and historical continuities in this region. In addition to pointing out the vast field of the symbolic, it also reveals the dimension of an increasingly globalized policy that involves entities guided by national and international projects, institutions and capitals, given the marking on the map of the site where a nuclear power plant is to be built, or even of the spaces irreversibly affected by the construction of the Itaparica hydroelectric power plant.3

The absence or presence of any element on the map is not a simple and technical option, but rather a complex operation: whatever is on the map may even refer to something that is actually no longer there to the eyes of an outsider —such as the islands of the São Francisco River now submerged under the Itaparica Hydroelectric Plant—, but is still made present in the dimension of a territory of lives whose physical, environmental and symbolic conditions are referenced, all intertwined in the worldview of these peoples. Creating a map between absences and existences is a powerful political act in the dispute for the inscription of reality.

But if disappearing from the map means becoming absent through invisibility, omission, and silence, to be on the map is to project subversions of symbolic and territorial power, to make collective existence and local potential visible. Social cartography expresses, therefore, an epistemological struggle in which Indigenous communities and quilombolas of Itacuruba dispute their own ways of conceiving, representing, and classifying spaces, owning geomatic techniques that are arbitrarily used to eliminate them. Being on the map means establishing a political confrontation; it is equivalent to saying that we live here and that we must be considered:

We the inhabitants of the Tuxá de Itacuruba village are neighbors of the probable nuclear power plant area, we are right next to where it is going to be built (Evani Campos, Tuxá Campos Indigenous people).

That is what we must show the people, to show society as a whole […], people are amused when I say: Nothing for us, communities, be it Indigenous, be it quilombola, be it gypsy… nothing for us, without us! That is why it is particularly good that we participate in the mapping work. It is a work done by us (Valdeci Ana, quilombola community Poço dos Cavalos).

We are interested in cartography so that this can be announced and disseminated in the news —or anywhere for that matter—, to state that there are Indigenous peoples, quilombolas, riverside dwellers, fishermen, an entire population next to where they want to build the nuclear power plant. (Jorge França, Pankará Serrote dos Campos Indigenous peoples).

The map drafted by the Indigenous communities and quilombolas of Itacuruba shows, unlike the institutional cartographic records, key aspects for understanding the socio-environmental conflicts involving traditional peoples and communities in this region of the sertão. The first aspect points to the effects of State action, through development policies, which have been affecting the social groups living in the “environments” expropriated by large projects.4 Mining Exploration; power plants; diversions in the natural watercourse of the São Francisco River and changes in its water level; private facilities for large-scale fishing and aquaculture are among the many ventures affecting the region since 1970. We are looking at a large cluster signaling traces of environmental damage and forms of violence set forth by a guideline defined by capital and led in consortia by the State.

As a second aspect, it is worth mentioning the diversification of mobilization strategies that begin to operate in a void of government action and to confront the consortia and corporations that expand into regions historically left behind and known for their backwardness. In this regard, being on the map is the very process that induces political actions that vindicate forms of resistance and political solidarity among traditional peoples and communities in this region. The map is thus a sketch of collective struggles that shape the repertoire of confrontations with the State’s development policy, which, in turn, contrasts with the presence of Indigenous groups and quilombolas in their territories.

Analyzing the map from the point of view of political dispute leads us to identify the dynamics related to the control over life (or death) and the right (or not) to exist regarding specific social groups. We must, therefore, understand the multilayered and blurred nature of these relationships and seek to recognize the pillars that support the power games that take form, adopt a name, and position themselves spatially.

The activities carried out in the heart of Pernambuco regarding Projeto Nova Cartografia Social derived in three fascicles: 1. Comunidade quilombola de Conceiçao das Crioulas, Salgueiro – PE (2006); 2. Pueblo indígena Xukuru doororubá, Pesqueira – PE (2012) y 3. Associaçoes e equipes de futebol do bairro de Santo Amaro, Recife – PE (2014). Regarding the activities conducted in Itacuruba, as highlighted here, a Newsletter was published along with a local map of the municipality and a synthesis map of collective actions and socio-environmental conflicts in the Sertão de Itaparica region. All the materials produced are available on the Projeto Nova Cartografia Social (PNCS) website. ↩︎

In Itacuruba there are three indigenous peoples (Pankará Serrote dos Campos, Tuxá Campos and Tuxá Pajeú), in addition to three quilombola communities (Ingazeira, Negros de Gilu and Poço dos Cavalos), that is, six different socio-political organizations that embody ethnic factors, ecological and gender criteria in self-definitions and territorialization processes of their own. Thus, we distinguish “Indigenous peoples” and “quilombola communities,” in view of the self-denominations existing at the local level. ↩︎

The “nova” Itacuruba, as its inhabitants say, is the city designed and built by Chesf to house, as of 1988, part of the population forcibly resettled from the “old” Itacuruba, whose municipality and farmlands were flooded by the Itaparica Dam. The Northeast Nuclear Power Plant, in turn, is a project of Electronuclear/Brazil’s Ministry of Mines and Energy to build a plant with six nuclear reactors and a total capacity of 6,600 megawatts on the banks of the São Francisco River, at a site located in the “new” Itacuruba. ↩︎

Environments understood as ecological spaces —inherent to life itself— and therefore, inevitably socio-political. ↩︎