Abstract

This essay examines the historical and contemporary relevance of quilombos in Brazil as symbols of Afro-descendant resistance and cultural identity. Originating from African diasporic traditions, quilombos have evolved into dynamic entities tied to their territories and traditions.

Despite legal progress since the 1988 Constitution recognizing Quilombola land rights, systemic barriers persist, with only a small fraction of quilombos achieving formal land titles. The 2022 Census identified over 1.3 million Quilombolas, primarily in Brazil’s Northeast, highlighting their resilience amid socio-political challenges. The essay emphasizes the need to safeguard Quilombola rights and integrate their legacy into Brazil’s broader historical and national narrative.

Fire!… They burned Palmares,

Canudos was born.Fire!… They burned Canudos,

Caldeirões was born.Fire!… They burned Caldeirões, Pau de Colher was born.

Fire!… They burned Pau de Colher…

And new communities have been born, and will be born, tiring them out if they keep on burning.Because even if they burn the written word, They will not burn the oral tradition.

Even if they burn the symbols, They will not burn the meanings. Even as they burn our people, They will not burn our ancestry.Mesmo queimando o nosso povo,

Não queimarão a ancestralidade.

Antonio Bispo dos Santos1

On December 3rd, 2023, Brazilian mainstream media outlets, Black movement activists, and even prominent political figures such as President Luis Inácio Lula da Silva mourned the passing of Quilombola philosopher, poet and political activist Antonio Bispo dos Santos, known as Nego Bispo. The author behind the conceptualization of contracolonialismo and cosmofobia,2 and one of the strongest voices in the struggle for Quilombola rights across Brazil, Bispo left a legacy that propelled the centrality of quilombos not just as fundamental to comprehend the plight of Black populations across the Americas, but also as subjects strategically positioned to inspire what Aílton Krenak would call “ideas to postpone the end of the world” (Krenak, 2019), particularly in face of the insidious impacts of climate change. Given the attention the death of Bispo received, one would expect quilombos in Brazil to be seen as the subject of fundamental human and political rights and to occupy a central place in the broader debate about the country’s historical narratives and the very construction of national identity. Yet, this supposition contrasts with a stark reality. Not only is the Quilombola identity continuously contested, but quilombos are still portrayed via monolithic images, as though stuck in the past. Such images do not fully capture the diverse social, political, economic and spiritual meaning of Quilombos in the present (Kenny, 2008; De La Torre, 2013). More importantly, the combination of both forms of erasure foregrounds the on-going forms of dispossession inflicted upon these traditional Black peoples. How could one make sense of what quilombos mean today? In what ways has the Brazilian state curbed the possibility of full citizenship to more than a 1.3 million people distributed across the country? More crucially, how have these peoples continued to resist despite the various attempts to, as Bispo would say, burn to their existence?

This short essay aims to contextualize the presence of quilombos in Brazil. I provide what I consider basic information to communicate a sense of how these populations have transformed the Brazilian political landscape, from their historical roots in Africa to present-day achievements and progress toward the recognition of their human and political rights. In the first section of what follows, I discuss what quilombos are and the historical context in which they emerged. In the second section, I consider the legal framework built over the past three decades to legally constitute Quilombola subjectivity, provide a quantitative perspective on their presence in Brazil, and discuss the challenges they face in guaranteeing their collective territorial rights. My goal is to lay the groundwork for readers to continue researching the reality of quilombos in the present.

Defining Quilombos

Over more than four hundred years, the word quilombo took on meanings that translate into a web of religious, linguistic, musical and bodily memories and symbols connecting different parts of the African diaspora, particularly Brazil. However, from a historical standpoint, the word kilombo, origin of the Portuguese term quilombo, has its roots in the Bantu languages of African peoples such as the Lunda, Ovimbundu, Mbundu, and Kongo, enslaved and brought to Brazil since the 16th century from regions of present-day Angola and Zaire (Munanga, 1996). That is, the conception of kilombo in Africa, which gives meaning to the phenomenon of quilombo in the diaspora, precedes the European colonial enterprise and the advent of African slavery. Though connected, the words have different meanings on both sides of the Atlantic. To Beatriz Nascimento, one of the main contributors to the conceptualization of quilombos within the Afro Diasporic thought, this fact provides for a fundamental theoretical leap, especially in a context where quilombos - or any Black experience - tends to be reduced to a dialectic opposition, to the antithesis of Europe. She argues that reclaiming the ancestral existence of quilombo prior to the Middle Passage is a necessary part of understanding this experience not as static and tied to slavery, but rather a dynamic, historical, continuous, process with a range of meanings across time and space (Nascimento, 1985). This is an important starting point. One can define quilombo as a practice of power and resistance relevant for all Black subjects in the diaspora.

To focus on what quilombos are in Brazil today, it is interesting to consider a translation that has recently been shared by the National Coordination of Articulation of Quilombola Rural Black Communities (CONAQ) at the end of the second edition of the Ato Aquilombar, held in Brasilia in May, 2024 3 . The main Quilombola movement organization in Brazil published a political letter directed at federal-level government officials, denouncing the various forms of violence faced by these peoples, from the violation of land rights, to the impacts of climate change in their communities, and obstacles in their access to public goods such as education and health. The letter began as follows:

We, Quilombolas, are the people of the land, the flowing waters, and the forests. For centuries, we have faced the harmful impacts of racism, machismo, poverty, and violations against our territories, our bodies, and our culture. Amid adversity, we are proud to say that each quilombo stands firm against so many injustices, preserving our values and traditions as the precious foundation of our struggle, which makes us who we are. (CONAQ, 2024b; pg 1) [translation is mine]

The self-definition as people “of the land, the flowing waters, and the forests” who resist by “preserving our values and traditions as the precious foundation of our struggle” adds another layer to the meaning of quilombos and connects their existence as to their territories and to their historical fight. Territory and struggle constitute inseparable and essential elements of what a quilombo is. It is a combination that characterizes Afro-descendant peoples across the Americas who recognize themselves as connected to histories of mocambos, maroons, cumbes, palenques, cimarrones, among other terms. All of these peoples will indeed share with quilombos the similar processes of formation linked to a territory and an African-rooted ancestral struggle. However, in the rest of this text I will specifically address manifestations of Afro-descendant resistance in traditional Black communities situated in rural and urban areas of Brazil.

With this understanding, it is also necessary to consider quilombos with reference to the place of Brazil within the larger context of the global African slave trade. The country was the last to abolish slavery in the Americas, in 1888. It also received 45% of the over 12 million enslaved people forcibly brought across the Atlantic as commodities between 1550 and 1850, the largest share among all the enslaved destinations in Europe and the Americas (Alencastro, 2018). Though these numbers communicate the centrality of Brazil, they might even be an underestimation, as they do not include the illegal trade, particularly after 1850. Nor do they reflect the lives that were lost in the Middle Passage for various reasons, from suicides to slaveship revolts and deaths from diseases or lack of water or proper ventilation (Mamigonia, 2017). Gomes (2019) shows that about 14 bodies were thrown in the ocean every single day for more than 350 years. So deep was the impact of the continued disposal of Black bodies onto Atlantic waters that it possibly changed the habits of various species of sharks which were able to locate the routes where they could easily find human flesh to feed (Gomes, 2019). Brazil’s comparatively central role in the history of African slave trade is thus fundamental to why quilombos emerged as a means of resistance, be it against the colonial system, as it was with Quilombo dos Palmares (Anderson, 1996), or be it against supposedly democratic structures of power, as it is with CONAQ today.

Quilombos in numbers and in the law

From a legal point of view, over the last 30 years, Quilombolas have made gains in the struggle for rights. The Brazilian state only began to employ the legal category of quilombos after the Promulgation of the Federal Constitution of 1988. With Article 68 of the Transitional Constitutional Provisions Act (ADCT), the right to land was recognized as essential for the cultural, social and economic reproduction of Quilombola communities. After that, Article 2 of Decree 4,887/2003 created the new legal category of comunidades remanescentes de quilombos (CRQ, descendants of [or, more literally, offshoots from] quilombo communities) as “ethnic-racial groups, according to criteria of self-attribution, with their own historical trajectory, endowed with specific territorial relations, with a presumption of black ancestry related to resistance to historical oppression suffered”.4

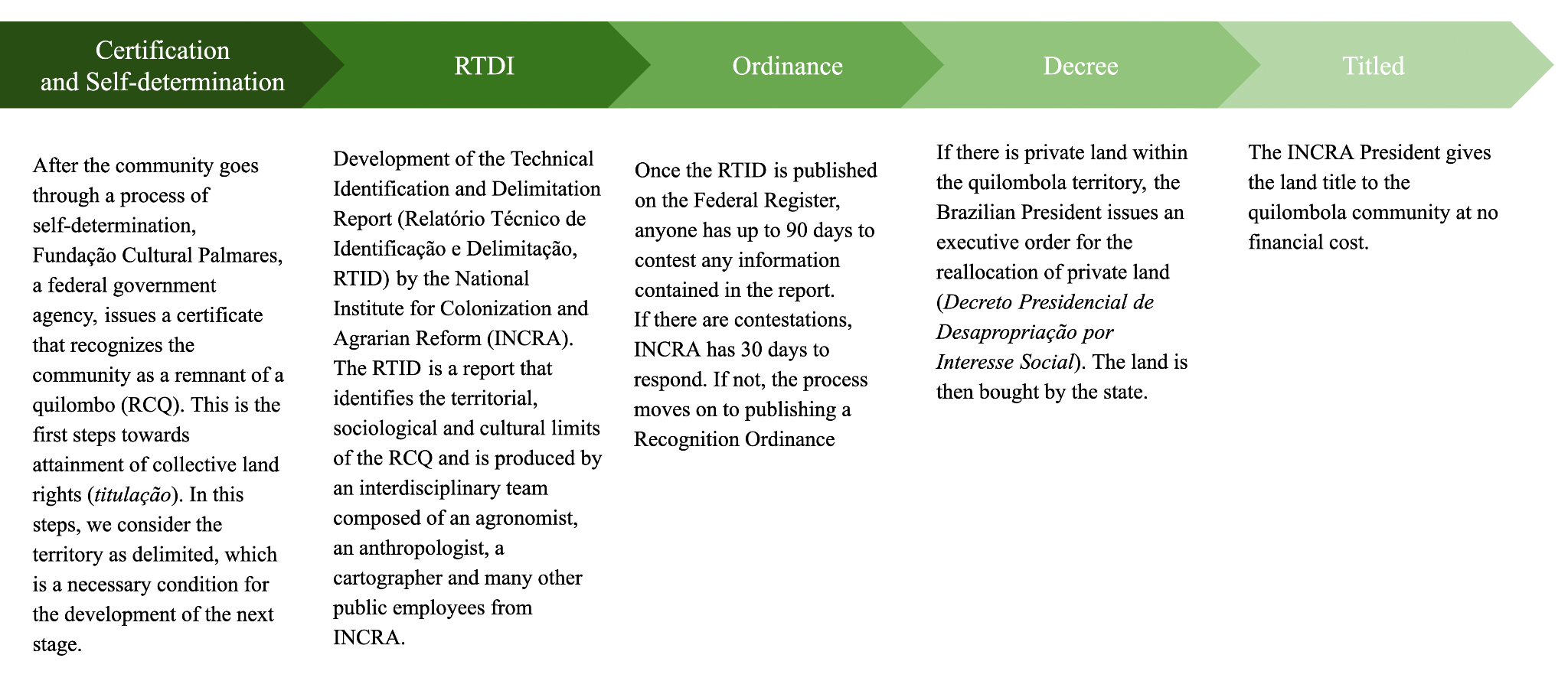

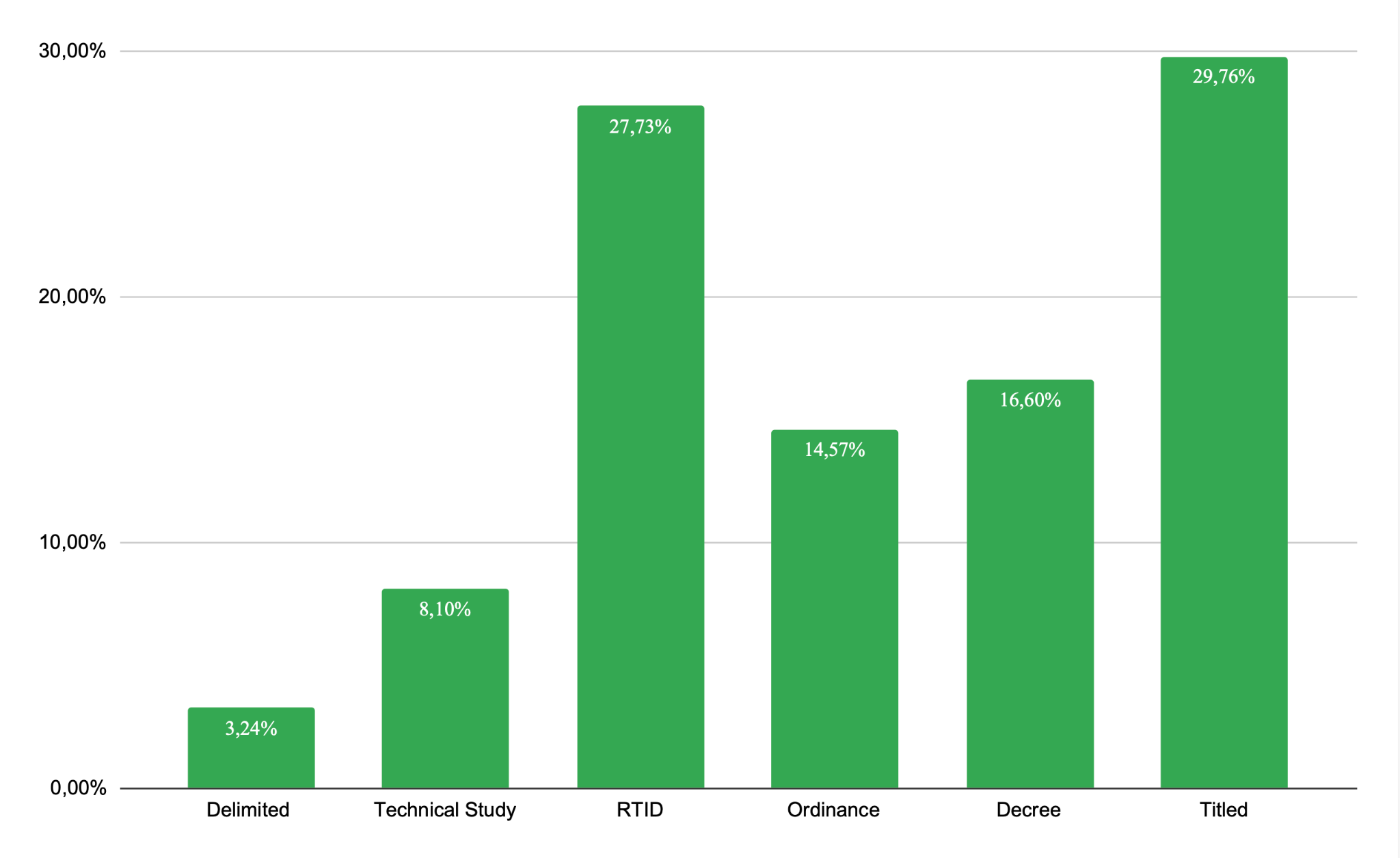

The significance of CRQ as a designation can be grasped when set alongside the principle of self-attribution, provided for in the Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization, which guarantees the need for “prior, free and informed consultation” in relation to any measure, legislative, administrative, business or from another segment that may directly affect the CRQs. Together with the Programa Brasil Quilombola, created in 2007, this legal principle regulated the process of titulação (titling) of Quilombola lands, attributing responsibility to different government agencies. This legal framework also aimed at structuring the Quilombola social agenda in terms of both access to land and the consolidation of an infrastructure to guarantee quality of life, inclusive of political rights and citizenship. In Figure 1, I explain the stages of Quilombola land titling. According to data from the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA), there are 2,849 communities certified by Fundação Cultural Palmares (FCP) - the initial stage of self-determination, - and, according to IBGE, other 3,260 communities yet not certified (officially identified as “outras comunidades)5. In addition to these, there are another 494 communities currently undergoing the land titling process (after receiving the certification by FCP), distributed across the six stages as shown in Graph 1. This distribution has not changed much in the past 15 years. At such a slow pace, a recent study has demonstrated that it would take 2,188 years for all Quilombola territories to receive legal title to their lands.6

Figure 1 - Step-by-step process of Quilombola Land Titling

Source: INCRA, 2022. Passo a passo da Titulação de Territórios Quilombolas. (Access here).

Graph 1 - Quilombola Territories by Titling Stages (MIR, 2023)

Source: INCRA, 2022.

Note: There are currently 484 Quilombola communities currently undergoing the land titling process.

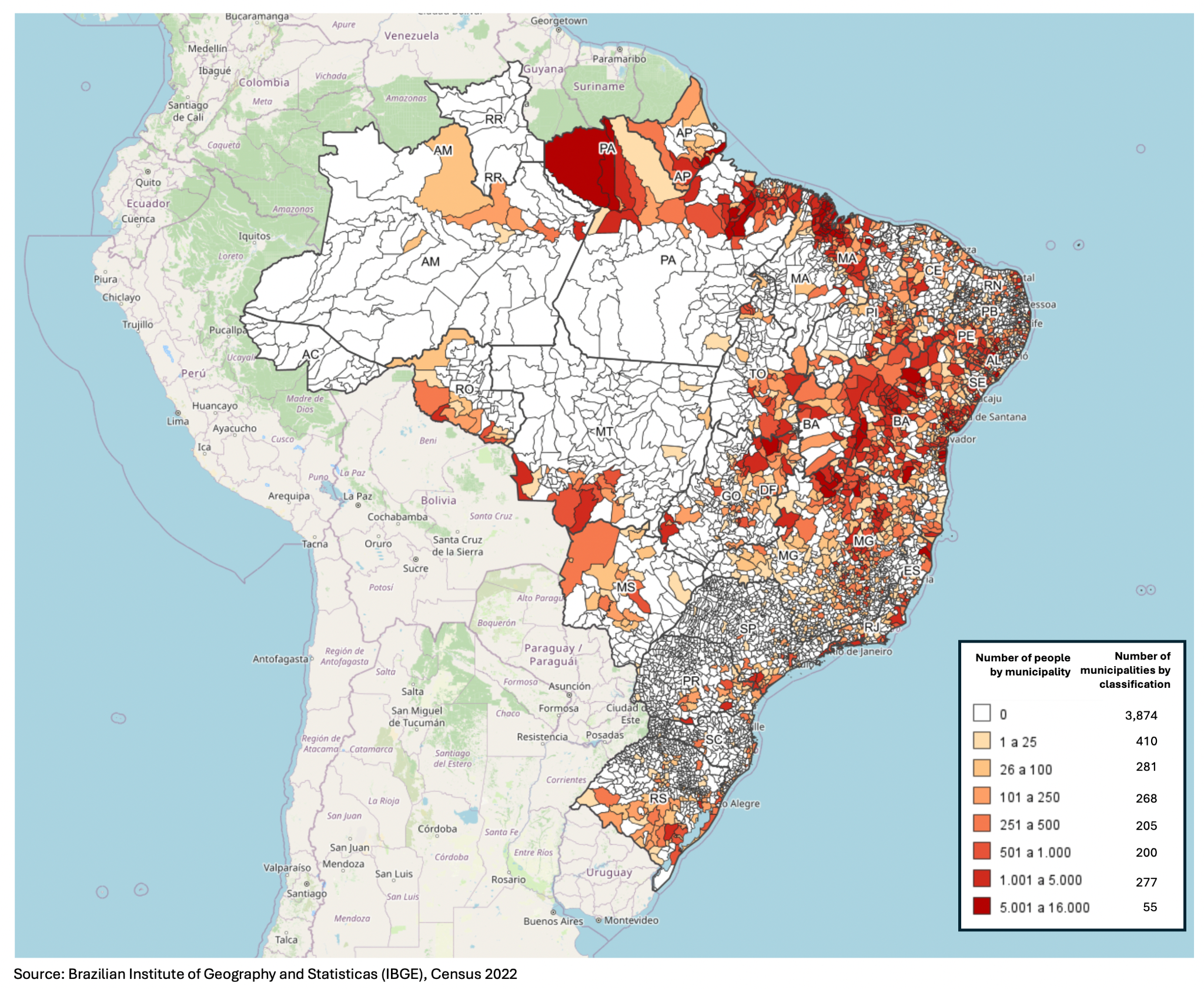

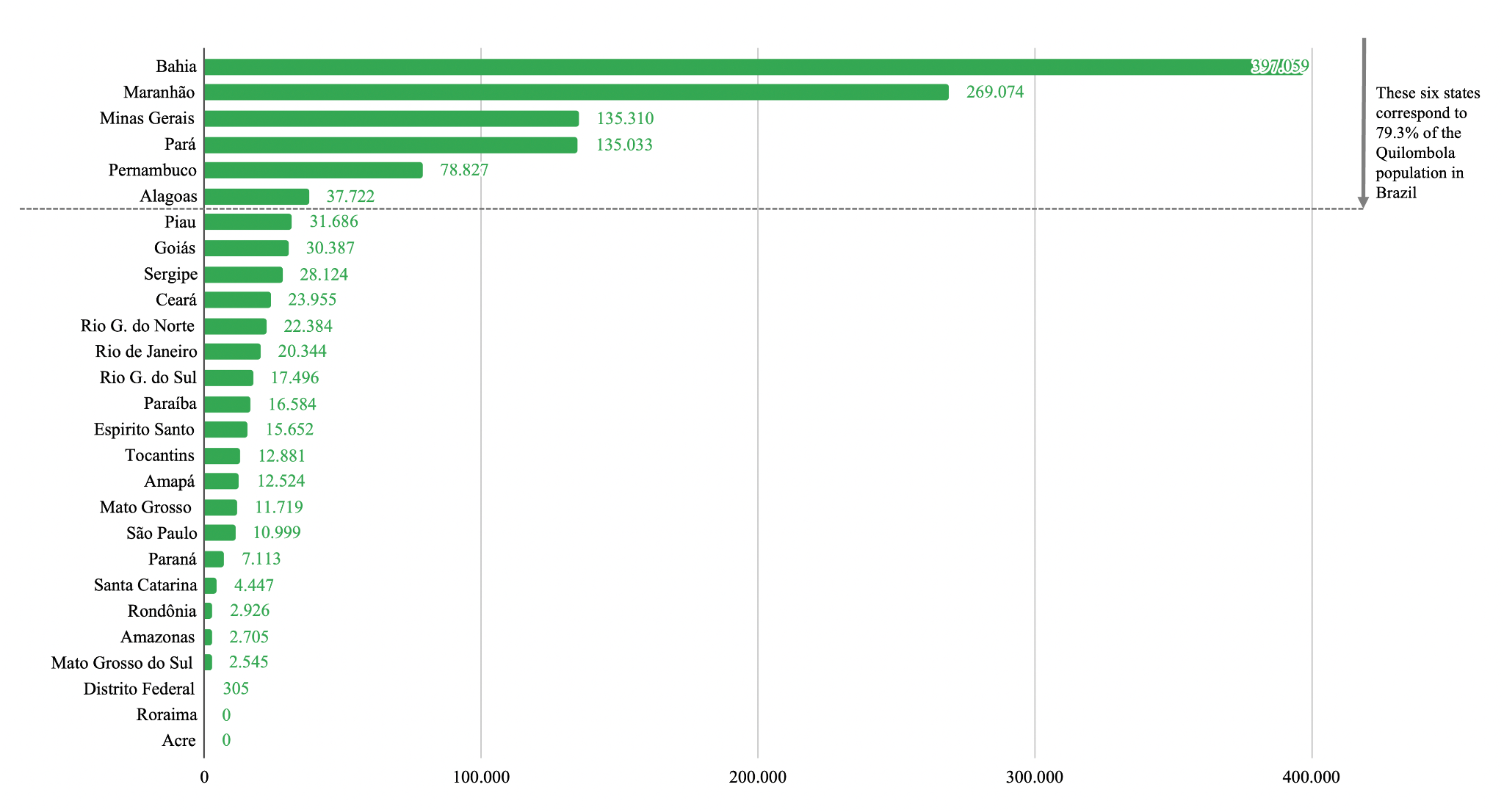

Lastly, it is necessary to put the Quilombola population in a larger demographic context. Investigating the numerical presence of quilombos in Brazil has only recently been made possible. The Brazilian Census of 2022 was the first to single out the presence of Quilombola populations. Over 1.3 million people self-identified as quilombolas7 (0.65% of Brazil’s population), distributed across 1,696 municipalities8, 24 states and the federal district (IBGE, 2023). Figure 2 below shows the geographic distribution of this population. The majority of the Quilombola population is located in the Northeast region of Brazil (68.9%) (IBGE, 2023). As seen in Graph 2, they are concentrated in six Brazilian states: Bahia (29.9%), Maranhão (20.3%), Minas Gerais (10.2%), Pará (10.2%), Pernambuco (5.9%), and Alagoas (2.8%). Together, these states correspond to nearly 80% of the Quilombola population (see Graph 1).

Figure 2 - Map of Brazil with the distribution of Quilombola population by Municipalities (IBGE, 2023)

Graph 2 - Quilombola population by Brazilian States (IBGE, 2023)

References

Anderson, R. N. 1996. The Quilombo of Palmares: A New Overview of a Maroon State in Seventeenth-century Brazil. Journal of Latin American Studies, 28 (3), 545-566.

CONAQ. 2024. II Aquilombar reúne milhares de quilombolas de todo o Brasil para reivindicar direitos. CONAQ Website. https://conaq.org.br/noticias/ii-aquilombar-reune-milhares-de-quilombolas-de-todo-o-brasil-para-reivindicar-direitos/ (accessed on June 13th, 2024).

________, 2024. Carta Política do II Ato Público realizado pela CONAQ “Aquilombar: ancestralizando o futuro”. CONAQ website. http://conaq.org.br/wp-content/uploads/CARTA-POLITICA-AQUILOMBAR-2024.pdf (accessed on June 28th, 2024).

de Alencastro, L. F. 2018. África, números do tráfico atlântico. Lilia Moritz. Schwarcz e Flávio dos Santos Gomes (orgs.), Dicionário da Escravidão e Liberdade (São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2018), 61.

De La Torre, O. 2013. Are they really Quilombos? Black peasants, politics, and the meaning of Quilombo in present-day Brazil. OFO: Journal of Transatlantic Studies, (1/2), 97-118.

Dos Santos, A. B. and Pereira, S. 2023. A terra dá, a terra quer. Ubu Editora.

Gomes, L. 2019. Escravidão–Vol. 1: Do primeiro leilão de cativos em Portugal até a morte de Zumbi dos Palmares (Vol. 1). Globo Livros.

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. 2023. Censo Demográfico 2022 Quilombolas: Primeiros resultados do universo. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE).

Kenny, M. 2008. Deeply Rooted in the Present: Making Heritage in Brazilian Quilombos. In Intangible Heritage, edited by L. Smith and N. Akagawa, pp. 165-182. Routledge.

Krenak, A. 2019. Ideias para adiar o fim do mundo (Nova edição). Editora Companhia das Letras.

Mamigonian, B. 2017. Africanos livres: a abolição do tráfico de escravos no Brasil. Editora Companhia das Letras.

Ministério da Igualdade Racial. 2023. Informe MIR - Monitoramento e Avaliação. Número 1 - Edição Censo Quilombola 2022 (accessed on June 28th, 2024).

Munanga, K. 1996. Origem e histórico do quilombo na África. Revista USP, (28), 56-63.

Nascimento, B. 1985. O conceito de quilombo e a resistência cultural negra. Revista Afrodiáspora, 3(6-7), 41-49.

Ribeiro, M. 2019. Políticas de promoção da igualdade racial no Brasil (1986-2010). Garamond.

Theodoro, M. 2014. Relações raciais, racismo e políticas públicas no Brasil contemporâneo. Revista de Estudos e Pesquisas sobre as Américas, v. 8, n. 1, p. 205-219.

Poem published by the National Coordination of Articulation of Quilombolas Rural Black Communities (CONAQ) in 2023. ↩︎

The concepts refer to Nego Bispo’s first book Colonização, Quilombos, Modos e Significados, published in 2015 by the Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia de Inclusão no Ensino Superior e na Pesquisa - (INCTI) at the University of Brasília (UnB). The publication is open access and can be found here. ↩︎

Ato Aquilombar is considered the largest event organized by quilombola movements in Brazil. Led by the National Coordination of Articulation of Quilombolas Rural Black Communities (CONAQ), this major political meeting gathers representatives from rural Black peoples from across Brazil and is considered a pivotal space for them to exchange lived experiences and traditional knowledge (saberes tradicionais) and debate the challenges faced by these peoples in different parts of the country. Both editions of Ato Aquilombar were held in Brasilia, capital of Brazil. This strategic location allowed for the event to both contribute to the preservation and strengthening of Afro-Brazilian cultural heritage, and to present a political agenda that centers policies designed to guarantee the legal rights of Quilombola peoples, such as access to land, health, and education (CONAQ, 2024). ↩︎

“Grupos étnico-raciais, segundo critérios de auto-atribuição, com trajetória histórica própria, dotados de relações territoriais específicas, com presunção de ancestralidade negra relacionada com a resistência à opressão histórica sofrida”. (Decree 4887/2003). ↩︎

IBGE, 2019. Base de Informações sobre Povos Indígenas e Quilombolas. ↩︎

Terra de Direitos, 2023. “No atual ritmo, Brasil levará 2.188 anos para titular todos os territórios quilombolas com processos no INCRA.” Access here. ↩︎

Following the international normatives as established by the Convention 169 of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and its ratification by Brazil in 2022, self-determination is the fundamental criterion to determine one’s ethnic belonging to a quilombo. As such, the identification of quilombolas occurred through self-declaration in the 2022 Census where people were asked to respond to the following open-ended question: “você se considera quilombola?” (do you consider yourself a quilombola?). In the case of a positive response, people were asked another open-ended question: qual o nome da sua comunidade? (what is the name of your community?). Quilombola specialists and social movement activists were part of the construction of this methodology, and belonging to specific Quilombola territories was, as I will discuss in more depth in this text, determined by whether people belonged to officially delimited territories, Quilombola groupings (agrupamentos) or other census areas associated with sparsely occupied Quilombola locations (IBGE, 2023). ↩︎

This corresponds to 30.47% of all 5,565 municipalities in Brazil. ↩︎