Examining the myth about the enslaved Agustina: Tadó-Chocó 1795

María Fernanda Parra Ramírez

Abstract

Two historical references stand out in the quest of the inhabitants of Tadó —currently the department of Chocó (Colombia)— to reaffirm their cultural identity. In the first place, King Barúle, who led an uprising of enslaved people between 1727 and 1729, seeking their freedom. Second, the life of Agustina, a Black enslaved woman, who took her master Don Joaquín de la Flor to court at the end of the 18th century. Agustina’s narrative is based on orality and the works of Yessica Spicker, in which she suggests and portraits a perspective of Black women. The documentation provides evidence of exploitation and punishment, including rape and forced abortions, endured by enslaved women during the colonial period. At that time, Tadó was a Spanish mining territory (or real de minas) that constituted the second town in the province of Nóvita. In this essay, I propose that the lack of criticism, substantiation, or validation of oral sources against documentary sources has made the narratives about the enslaved Agustina de Tadó contribute to perpetuate stereotypes that do not correspond to empirical evidence. Agustina, a Black woman silenced like many others by history, deserves to be vindicated, redefined, and repositioned in national history to never again be stripped of her humanity.

Violence remains deeply rooted in today´s society. Its continuity prompts and inspires us to fight for the equality and dignity of all human beings, starting with gender issues. There are still remnants of patriarchal, macho, and androcentric mindsets, through which women are placed in a subordinate, oppressed, subjugated condition, and considered less capable than men. This thinking transcends the spaces of academic, social, political, economic, cultural representation and is deeply rooted in the family.

2014 was a crucial year for me. In that year I began to come out of my bubble, out of my shell and my unconscious hiding place of denial as a Black woman, in which I did not understand my true value and much less my place in society. I faced all kinds of racist and sexist violence, but I maintained a complacent silence out of ignorance of my own strength. I discovered that this strength comes, not in spite of, but precisely from my own origin as a descendant of Africans who have overcome the transatlantic journey and reinvented themselves in the “New World.” This strength also came from the stories of my ancestors, but above all from the greatness of every contribution we have made to humanity. Starting to discover all of this as an adult woman was like breaking the chains that had tied me to stereotypes of oppression, which had forced me to endure derision, racism, machismo, patriarchy, sexism, the imposition of a religion, but above all, androcentrism.

This new awareness led me to examine, discover and rethink myself as a person and as a Black woman. In this search, I decided to take specific actions to vindicate the value, role, and contributions of Black women in all areas. I chose to revalue the great legacy of resistance that we inherited from numerous women of the past, which we must advance with responsibility in order to pass it forward to present and future generations. Seeing in these historical women new references will help us rediscover ourselves, inspire us and understand the power that lies within each one of us. Black women claim and demand a change of representation in all narratives. Our condition as human beings, which we have been building, just like men, in a society that has marginalized us, must take precedence. For this reason, a different reading of the past becomes necessary and urgent, because the one that has been conducted to-date continues harming us as Black women, as we carry in our being the traces of dehumanization, objectification and sexualization processes.

We must not continue to naturalize or perpetuate the current power and gender relations. They have been socially constructed and are called to disappear to give way to other forms and ways of agency. I am sharing the resignification that author Dora Barrancos makes of the term “agency” in her book “Historia mínima de los feminismos en América Latina” (2020) to make known the feminine collectives committed to transforming the conditions of existence, to modify the lack of recognition and social subordination.

With this preamble, let us move on to our analysis. Our story takes place in Tadó, a Spanish mining area (or real de minas) that constituted the second town of the province of Nóvita, during the Viceroyalty of the Nuevo Reino de Granada —including the territories of Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Venezuela— today known as the department of Chocó. During colonial times, this region was characterized by its high volume of gold production through slave labor. Today, the inhabitants highlight two of their best-known historical references. The first one is King Barúle, who created a libertarian movement between 1727-1729 along with enslaved Mateo Mina and Antonio Mina, and encouraged an uprising against their masters, using as a slogan, “killing whites is good, only then will Chocó end”. The second historical reference lies in the life of Agustina —Black and enslaved woman—, based on oral tradition, and on a work written by Jessica Spicker in 1996 entitled “Mujer esclava. demografía y familia en la Nueva Granada 1750-1810.” What is significant is that Agustina —as a Black woman in a colony, and in the context of enslavement— marked a historical milestone for having taken her master Don Joaquín de la Flor before a judge and reported his continuous rapes, mistreatment, and punishments, plus the fact that he caused her an abortion.

Agustina´s story gained momentum with the work among the community members, which inspired many cultural experts, men, and women leaders to write about her on their websites, blogs, social media, articles and even books. This was the case of the writer Fabio Teolindo Perea Hinestroza, who wrote “Hechos relevantes de la etnohistoria del Chocó siglo XVII- XVIII,” to which we will refer later.

Before analyzing the myth, it is necessary to contextualize the historical circumstances around Agustina´s life. Agustina had been bought by don Joaquín de la Flor for the services and care of the house. This situation exposed her to vulnerable conditions in a reduced space where her master could have physical and sexual access to her. Indeed, in the past —still with very distressing present effects—, those who held power created legal, economic, political and social conditions to dominate and control other people. Marginalization went to the extreme of dehumanizing, objectifying and brutalizing others to perpetuate their conditions of privilege. This can be seen in the case of enslaver Joaquín de la Flor and enslaved Agustina. Agustina´s case was not unusual, but rather the norm for 1,000 and perhaps 1,000,000 women who for over 400 years lived in America in conditions of slavery. Don Joaquin de la Flor represents hundreds of masters who had control of the slave society and who —even in in today’s society— still have the control and power to inflict all kinds of punishment against the dominated and/or subordinates.

In the General Archive of the Nation of Colombia, Bogota, we can find the “Juicio Contra Don Joaquín de la Flor” (or “Trial against Don Joaquin de la Flor”).1 This document allowed me to learn that a trial was held against the slave owner for mistreatment and rape of his enslaved woman, in 1795 in Tadó. The colonial domination structure physically and legally re-victimized the enslaved Black woman in the defense of the white man, who feared losing his “good name and honor.” As I read the case, I also noticed the impossibility of interethnic love relationships due to social and religious barriers. I could clearly observe the difference between rectification and punishment, the latter applied with careful planning, severity, and cruelty. Consequently, the abortion of the baby Agustina was carrying in her womb had taken place. The complicity of the ecclesiastical authorities can also be traced, since priest José Ignacio Varela kept silent about the affair and did not protect Agustina, who had requested his help on two occasions. Rather, priest Varela decided to remain silent. Only after much insistence from Agustina begging for help, did the priest inform in writing to corregidor Manuel Sanclemente and governor José Michaely, who in turn appointed don José Álvarez del Pino as commissioned judge to initiate the trial in 1795. The file reveals the expert´s inhuman behavior to hide the stain implied in having children with enslaved women and the cruelty he would be capable of in order not to be subjected to public scorn. The impunity shared among those who wielded power to benefit men who perpetrated these violations in the bodies of Black women and the constant coercion through the exemplary consequences that those who dared to report the crimes would suffer. In Agustina’s case, in addition to losing the judicial proceedings, don Joaquín de la Flor decided to sell her to a slave master named Maria Manuela Murillo, who used her services to take care of her house and raise her children.

Agustina never becomes a maroon in the flesh, that is, she does not flee from her master’s yoke to live a life as a free woman, alone or with other enslaved women and men. Her behaviors reflect some submission. This is quite distinct as she has always sought justice by resorting to the protection of those who had power and who kept enslaved people in their charge. She did not encourage, nor did she start a revolt, and her behavior was never rebellious. We do not know what happened to her afterwards, since we do not know the facts of her death and we do not know how, when or where it took place.

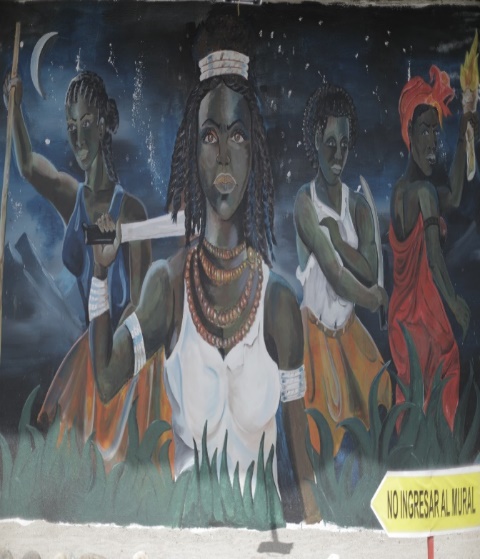

Sculpture crafted in 2009, Municipality of Tadó, Central Park. Photograph Maria Fernanda Parra Ramírez

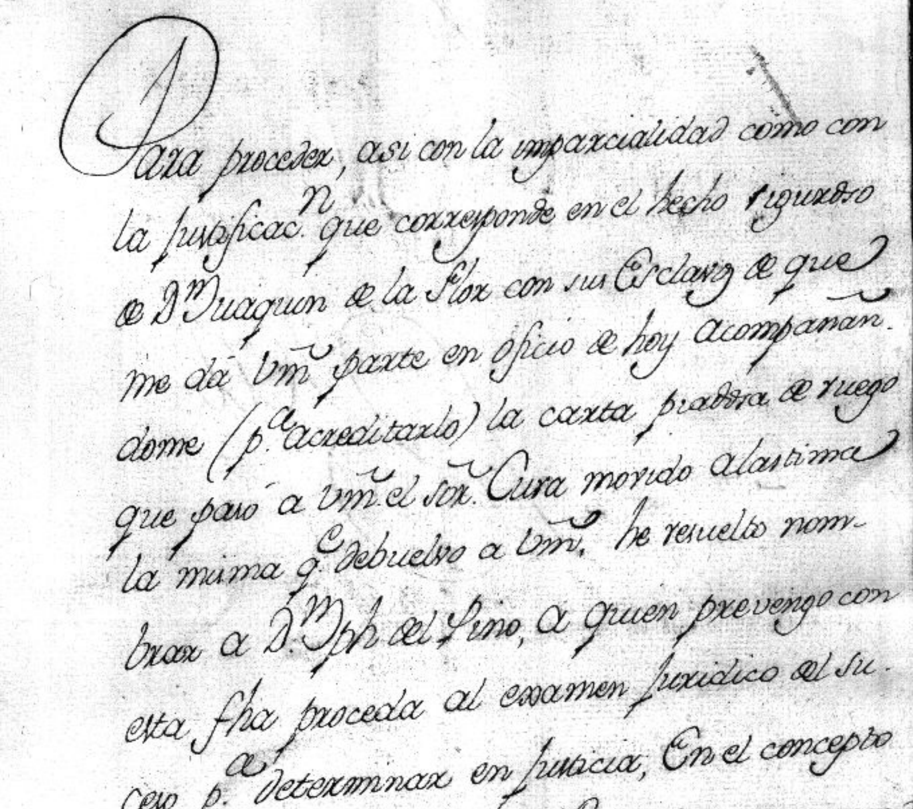

Representation of Agustina as a maroon. Source: Fabio Teolindo Perea Hinestroza, “Hechos relevantes de la etnohistoria del Chocó siglo XVII- XVIII,” 98. Photo by María Fernanda Parra Ramírez.

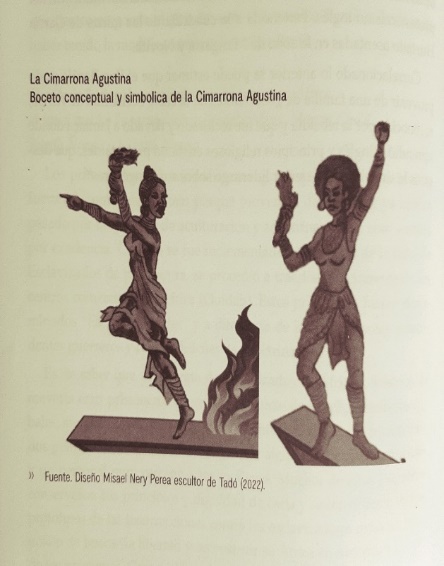

Mural. Municipality of Tadó, Chocó. Photo by María Fernanda Parra Ramírez

According to the archive information, the lack of criticism, substantiation, or validation of oral sources against documentary sources has made literary and artistic narratives about the enslaved Agustina de Tadó contribute to perpetuate stereotypes that do not correspond to her history.

| THE MYTH | THE ARCHIVE |

|---|---|

Maroon - Seductive, seduced. Orality about the sexualization of her body. | Enslaved and coerced, raped and abused. Her body´s sexuality was abused and violated. |

Direct and personal actions through which she caused damage to her master: _Dishonor by bringing him before a judge _Fleeing and arson - loss of her master's property. | Judicial channels, action, or appeal before the courts for the recognition of a right: Ecclesiastical power— Resorts to Father Ignacio Varela for his protection and for him to help her get rid of her master's cruelty. |

Image number 1 corresponds to a sculpture made in 2009. The project was part of the people of Tadó´s initiative to build two monuments, one in the name of Barúle and the other in the name of Agustina, both as symbols of the liberation struggles that took place in Tadó. These monuments, which are still located in Tadó´s central park, are a must for visitors coming to the municipality. With this monument, oral history has gained strength and has reasserted much of the rebellious behavior of its population that, despite not preserving palenque traditions and customs, still seeks to reaffirm its identity as a land of Maroons.

Image number 2 corresponds to a sketch to build a bronze sculpture for 2022 (still not carried out). As part of a project to uphold the identity of Tadó´s municipality, writer Fabio Teolindo Perea Hinestroza, depicts on page 98 of his book entitled “*Hechos relevantes de la etnohistoria del Chocó siglo XVII- XVIII” (*or Relevant facts of the 17th-18th century ethnohistory of Chocó). In his attempt to contribute to these collective imagery, Perea Hinestroza creates a post-modernist sculptural project in which Agustina´s image appears in the style of a Greek nymph in movement, with her right hand wielding the terrifying fire that reminds the white people of the destruction it can cause and that, according to the myth, she used to set fire to some houses in the municipality. In addition, her left-hand points to the future of freedom, towards which Black women and all enslaved people, but above all the Tadó society, should advance.

Image number 3 corresponds to a mural intended to validate that Tadó was and is a land of maroons. In addition, its women are rebels because of the influences left by enslaved Agustina. The mural is part of a project with which leaders of Tadó seek to convey this message to locals and strangers who visit the municipality. However, the legacy of colonialism is evident in every stroke along this mural. Agustina is seen as a hyper-sexualized, maroon, libertarian, and warrior female. This projected image reaffirms the intention that other Black women recognize her as a reference of struggle and resistance.

The study of this case is important insofar as it allows us to unveil the other side of the story, and helps us decolonize human beings and knowledge. In this way, we seek to give Agustina her rightful place in history. We make it clear that Agustina was not a maroon who physically escaped from the place where she was enslaved, that is, she did not commit any marronage, nor did she rise up against her master in a direct way. Agustina did seek help repeatedly, with no response, despite the evidence of multiple abuses, mistreatments, oppressions, and violations to which she was subject in her condition of dehumanized, objectified, object, or worthless body. But Agustina, this Black woman, and many others silenced by history, deserve to be vindicated, redefined, and repositioned in history so that they will never again be stripped of their humanity.

That is why we proclaim Agustina, the enslaved woman from Tadó-Chocó, as a symbol of No to Violence against Black women in Colombia!

Bibliography:

Barrancos, Dora. Historia mínima de los feminismos en América Latina. El Colegio de México, 2020.

Perea Hinestroza, Fabio Teolindo. Hechos relevantes de la etnohistoria del Chocó siglo XVII- XVIII. Design, layout and printing: Taller Artes y Letras SAS, 2022.

Spicker, Jessica, “Mujer esclava: Demografía y familia criolla en la Nueva Granada, 1750-1810.” Tesis de grado. Universidad de los Andes, 1996.

AGN, Fondo Negros y Esclavos, Cauca series, volume I, ff 671- 678. ↩︎