Abstract

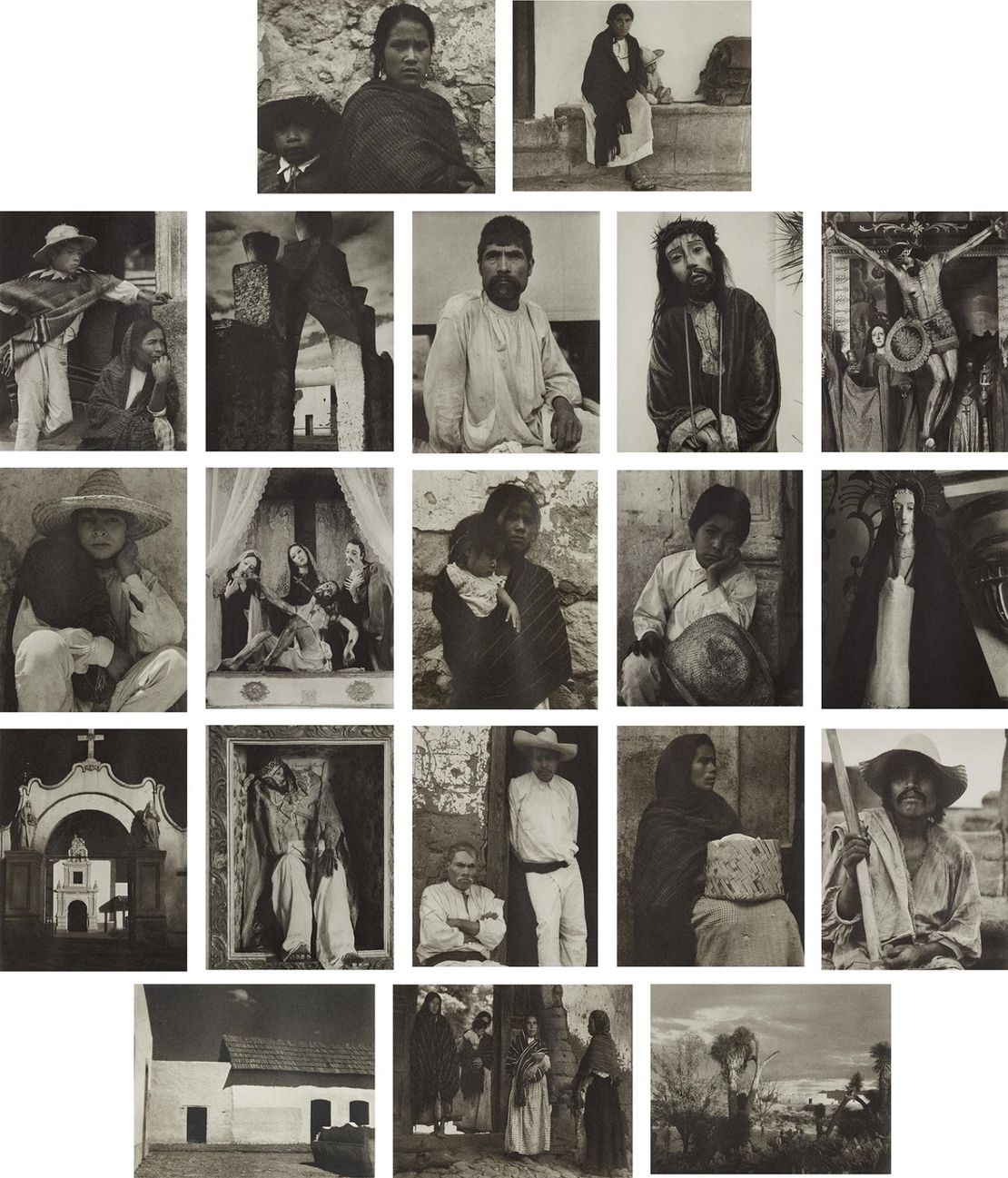

This short essay discusses Paul Strand’s reflections on folk art in Michoacán, based on a report he authored on behalf of the Mexican government in 1933. Strand, a renowned American photographer, examined the conditions of artisans in Uruapan, recognizing their aesthetic potential but also noting the oppressive colonial influences imposed by hegemonic forces. His Marxist perspective attributed the artisans’ creative limitations to their subordination to foreign aesthetic models—both national and international—that hindered their artistic autonomy. This opinion was shaped by his own experience as a member of the Photo Secession, a group that cemented photography’s status as an art form in the first decades of the 20th century by arguing that its direct connection to reality could reveal the authentic American experience, which had been obscured by Eurocentric aesthetic paradigms. Despite its insightfulness, Strand’s report fails to consider the artisans’ perspectives. His sympathy, while genuine, is tinged with paternalism. Today, Uruapan hosts the largest folk art market in the Americas, highlighting the ongoing importance of craft production for local communities. The fair attracts many of the same parties described by Strand—producers, state authorities, tourists, and collectors—representing the complex ecosystem around folk art.

On June 2nd of 1933 composer Carlos Chávez, head of the Fine Arts Department of Mexico signed an official document commissioning his friend, American photographer Paul Strand, to “carry out a special study in Michoacán and pull together the documentation needed to support a plan for the filming of educational films.” However, the report that Strand turned in after his travels to the state of Michoacán doesn’t really fit this mission. There is not a single word about plans to make films in the area. Instead, he delivered a report describing the popular art of the region and especially its conditions of production. Strand’s text denounces the conditions that oppressed the artisans of Michoacán during that period and, according to him, made the full development of their creativity impossible. Today, we would identify what Strand describes as colonialism. The photographer traced the origin of these problems to the peripheral status of the artisans (many of whom were part of indigenous populations) in cultural and economic terms; to their dependence on external entities that shaped and continue to shape aesthetic preferences, as well as the cultural goods market.

Strand wasn’t an expert on this subject, and he only wrote his report from being in the area for a few days. Nonetheless, he had significant prior experience as a photographer who transitioned into an artist. Strand belonged to a generation that cemented photography as an artform in the United States. Previously, it had been perceived as a craft: technical and creative but mechanical and utilitarian. Having experienced this transition himself allowed the photographer to approach the writing of his report with a special empathy towards the artisans’ condition. Despite not having an in-depth knowledge of the context of the artisan, he was able to grasp the structural problems that burdened them.

Before traveling to Mexico, Strand had been the poster boy for the Photo Secession, a group of photographers based in New York City which in the 1910s had pushed for the recognition of photography as an artform. Some of its most recognized members were Alfred Stiglitz, Eduard Steichen, and Alvin Langdon Coburn. They embedded their goals for photography within a broader objective for American art at the time: to gain autonomy from European aesthetics. Art in the United States didn’t have the prestige that it has today and, at the time, was considered marginal and derivative vis a vis European art. The Stiglitz group argued that due to its “directness” photography was the best medium to reveal the essence of the American experience, which they considered buried by Eurocentric paradigms in other arts. This move allowed them to become relevant as artists, and it emphasized their relationship to other important cultural actors of the era, such as Georgia O’Keeffe and Waldo Frank. The achievement of artistic autonomy for photographers during this period came hand in hand with a deep reflection on the importance of establishing regional autonomy for the American artistic space from the hegemony of European modernist art.

They cultivated a style of “straight photography,” conceiving it as a fully American art, one that faithfully expressed the reality of its environment and thus freed itself from external aesthetics. This relationship between artistic autonomy and regional autonomy is interesting in the Mexican context. A similar dynamic is visible in the quest for national identity during the same period, crystallizing in the notion of Mexicanness. This process gave rise to significant artistic movements like Mexican muralism. However, it is important to recognize that this strategy wasn’t accessible to all artistic practices. Folk-art in Michoacán, artistic objects originating from regions and identities subordinated to the hegemony of the Mexican nation, which occupied a peripheral space within a peripheral country never really had this option. This interweaving of histories and objects seems conducive to pondering how certain practices manage to establish themselves as art and what circumstances prevent this from happening in other cases.

In this era, both in Mexico and the US the notion of “modernist primitivism” was important for developing national aesthetic identities. The wake of WWI, saw the wide circulation of ideas such as those associated with Oswald Spengler, about the looming decadence of Europe. It seemed to be a moment of change in world geopolitics. In the realm of art, in part as a reaction to this, modernism recurred to what they called “primitivism”: the idea that western art needed to look receptively to primitive cultures and revitalize itself by appropriating formal qualities to restitute what had been lost through modernization and rationalism. In Europe this strategy can be seen in several of the most important artists of the era, such as Matisse, Gaugin, or Picasso. However, modernist primitivism represented something different in the Americas and as a discourse became key to the articulation of relevance in the American context. The reason for this is that it destabilized the long-lasting prejudice that had made originality and invention mostly a European privilege, with other places in the world consigned to following and imitating. Modernist primitivism, articulated by the Eurpean avant garde works almost as an inversion of this structure, and its ideas were picked up by artists across the Americans. At first glance, it might seem as though this adoption cemented the traditional flow diagram from Europe to the American periphery, but ideas of primitivism were a promethean fire.

Artists all over the Americas saw this strategy as more natural for their contexts than for those of European artists. Borrowing Hal Foster’s terms from “The Artist as Ethnographer”, European modernist primitivism seemed to “other” the self more than it ‘selved’ the other”1 because alterity was artificially imported from outside. In comparison, peripheric modernisms had local access to what was identified as “primitive”. This meant that modernist primitivism in these contexts was a discourse held not only by artists but also by the political class. It could be used as a tool by non-European societies to achieve a more autonomous position.

A version of modernist primitivism became key in Mexico and the US, among other countries, to argue for growing as nations, for becoming important as artistic cultures and as political and economic arenas. The vitality of the primitive essence of the Americas, if guided through modern models, would warrant bright futures. In Mexico the use of this kind of primitivism can be found in the glorification of local pre-Hispanic empires like the Mexica and Mayan; in the valorization of contemporary rural indigenous character; and, of course, in the ideology of mestizaje, which came to be the embodiment of this amalgamation of new and old. In the US, modernist primitivism strategies can be traced to the value assigned by the New Deal to the strength and dignity of the working class through corporations such as the Farm Security Administration. This is easier to identify in its portrayals of rural poverty, but there were features of it in the representation of the urban proletariat as well. It can also be appreciated in the turn toward preservation of anything that could be perceived as national heritage: natural landscapes became national parks and Native American cultures2 became an important part of the foundation that upheld American culture, there was also an anthropological interest in jazz, migration, and popular culture in general3.

These were some of the most socially progressive years in Mexico and the US. In Mexico the state agenda at this time was still fueled by the political energy of the popular revolution that ended in 1917. In the US, the New Deal constituted itself as a response to the great depression, looking to alleviate the struggles of the dispossessed masses. The strategy of modernist primitivism was perceived as inclusive and democratic. It made traditionally marginalized entities visible in the social and offered them a sense of citizenship. However, it also implied their subservience to the logic of nationalism, the cooptation of their identities, and the negation of autonomy. This is something Strand observed in his report. He identified many of the problems he saw in artisans’ practice as related to their subordination to the Mexican system and its desires.

In his report Strand recognizes that there is a “rather remarkable craftmanship” devoted to the production of Uruapan’s lacquers. However, in a rather controversial way he describes the resulting works as “mechanical and unaesthetic”4. Strand relates this apparent paradox to a disconnection between the art and the reality of the craftsmen: “Although these people live among fruits and flowers and birds and all the richness of a semi-tropical land, the floral designs upon their bateas are stylized in a dead and insensitive pattern”. He also described the style of the lacquers as foreign, insofar as it was plagued with what Strand called “pseudo-greek and pseudo-aztec” motifs. This is a crucial characteristic for him because he blamed this oppressive influence of external and antiquated aesthetic models for impeding the artisans from using their own imagination freely and therefore achieving the status of artists. It’s particularly interesting that the European Greek influence was placed on the same plane as the “Aztec” aesthetics. A different observer, especially one who conceptualized folk art from the region as fully within Mexican art, might have seen more of an organic relationship between the indigenous Purépecha artisans and the Aztec Empire. For him, however, pernicious European influences, as well as local primitivist cliches, made it difficult for the artisans to be active, contemporary agents. Heavily influenced by Marxism at this time, Strand saw them as an alienated labor force condemned to the mechanical production and reproduction of objects to be sold elsewhere.

Strand focused on the city of Uruapan, Michoacán. It’s where he spent most of his time in the state. Folk art is still very important in the city. For two weeks every year, Uruapan hosts the largest folk-art market on the continent. The event, which begins each year on Palm Sunday, completely overtakes the central square of the city. It brings together around 1,500 artisans from 50 communities all over the state and even from other places in the country where folk art is an important economic activity, such as Guerrero and Oaxaca. Additionally, it hosts a competition that rewards pieces of outstanding technical and creative quality. The sales of the works presented in this competition alone amounted to over a quarter of a million dollars in 2023. The total economic impact of this event was 5.5 million that year. These figures highlight the contemporary importance that folk art production continues to have in the region, especially for producing communities. It’s important to note that craft production is the primary source of income for most of the families who come to the square to sell their products.

The Uruapan craft fair exerts a strong gravitational pull that summons the multiple entities involved: producers, state and federal authorities interested in promoting these cultural products, resellers, domestic and foreign tourists, collectors, and representatives of private funds with programs dedicated to fostering folk art. In this sense, it presents a unique opportunity to examine the different layers that comprise this phenomenon in the region today. Despite his acumen Paul Strand’s report did not evade the biases of the time. His reflection on the folk art of the state of Michoacán is unilateral and excludes the voices of the subjects he writes about, thus tending to perceive artisans as passive entities, exclusively victims in the grand scheme of things. This interpretation is blind to the historical process that allowed artists from the Americas to take part in the artworld despite the initial hegemony of Europe in economic and aesthetic terms.5

Bibliography

Antliff, Mark, and Patricia Dee Leighten. “Primitive.” In Critical Terms for Art History, edited by Robert S. Nelson and Richard Shiff. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Berger, John. About Looking. 1st Vintage International ed. New York: Vintage International, 1980.

Bourdieu, Pierre. The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1996.

Frank, Waldo David. Our America. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1919.

Gabara, Esther. Errant Modernism: The Ethos of Photography in Mexico and Brazil. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008.

García Canclini, Néstor. Culturas Híbridas: Estrategias Para Entrar y Salir de la Modernidad. Mexico City: Grijalbo, 1990.

Goldstone, Andrew. Fictions of Autonomy: Modernism from Wilde to de Man. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Haran, Barnaby. “Documenting an ‘Age-Long Struggle’: Paul Strand’s Time in the American Southwest.” Art History 43, no. 1 (February 2020): 120–53.

Hegeman, Susan. Patterns for America: Modernism and the Concept of Culture. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001.

Krippner, James, and Fundación Televisa. Paul Strand in Mexico. 1st English-language ed. New York: Aperture, 2010.

Krippner, James. “Traces, Images and Fictions: Paul Strand in Mexico, 1932–34.” The Americas 63, no. 3 (2007): 359–83.

León, Francisco de, and Gabriel Fernández Ledesma. Los Esmaltes de Uruapán. Mexico City: D.A.P.P., 1939.

Parezo, Nancy J., and Lisa Munro. “Bridging the Gulf: Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina on Display at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition.” Studies in Latin American Popular Culture 28 (2010): 25–47.

Penhos, Marta. Ver, Conocer, Dominar: Imágenes de Sudamérica a Fines del Siglo XVIII. Buenos Aires: Siglo Veintiuno Editores Argentina, 2005.

Roberts, Jodi. “Ethnography.” In The Matter of Photography in the Americas. Stanford, CA: Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University and Stanford University Press, 2018.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. 1st Picador USA ed. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977.

Stallings, Stephanie N. “The Pan/American Modernisms of Carlos Chávez and Henry Cowell.” In Carlos Chávez and His World, edited by Leonora Saavedra, 28–45. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Strand, Paul. “Photography.” Camera Works 3 (1917): 3–4.

Strand, Paul. “Report of Paul Strand on Trip to Michoacán.” Center for Creative Photography Archives, Ag 17, box 31, folder 2.

Strand, Paul. Paul Strand, Southwest. 1st ed. New York: Aperture, 2004.

Susman, Warren. Culture as History: The Transformation of American Society in the Twentieth Century. New York: Pantheon Books, 1984.

Yates, Steve. Transition Years: Paul Strand in New Mexico. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico, 1989.

Foster, Hal. “10. The Artist as Ethnographer?” In Traffic in Culture: Refiguring Art and Anthropology edited by George E. Marcus and Fred R. Myers, 302-309. Berkeley: University of California ↩︎

Particularly interesting in this regard is W. Jackson Rushing, Native American Art and the New York Avant-Garde: A History of Cultural Primitivism (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1999). ↩︎

Two very good sources to understand the role of primitivism in New Deal culture are Hegeman, Susan. Patterns for America: Modernism and the Concept of Culture, Princeton University Press, 1999, and Warren I. Susman, “The Culture of the Thirties, ” chap. in Culture as History: The Transformation of American Society in the Twentieth Century (New York: Pantheon Books, 1984), 182 ↩︎

All of the quotes from his report are from Strand, Paul. “Report of Paul Strand on Trip to Michoacán.” Center for Creative Photography, Ag 17, box 31, folder 2. ↩︎

In recent years decolonial struggles for indigenous autonomy in the region have catapulted collectives and individuals into the artworld. ↩︎