Abstract

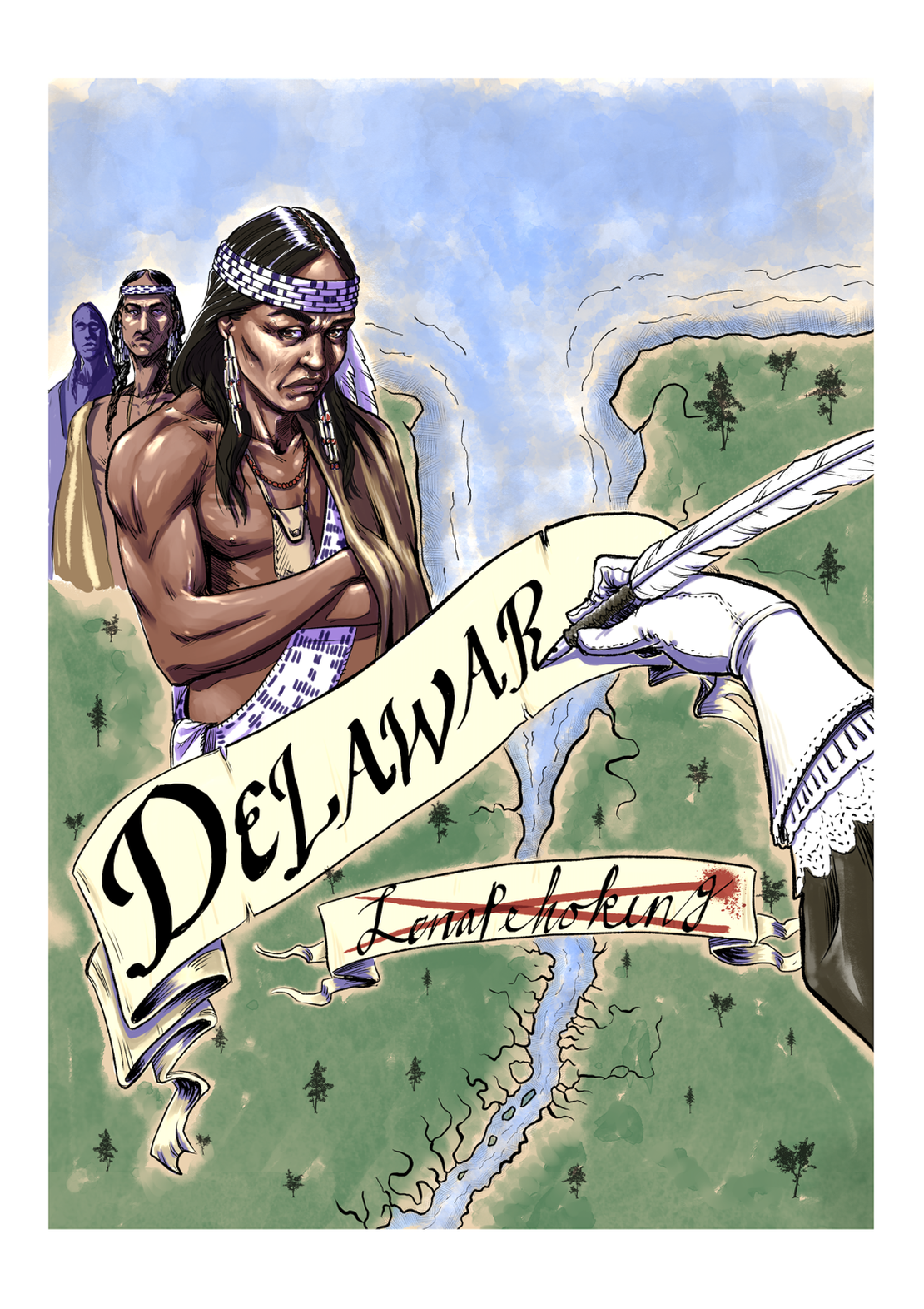

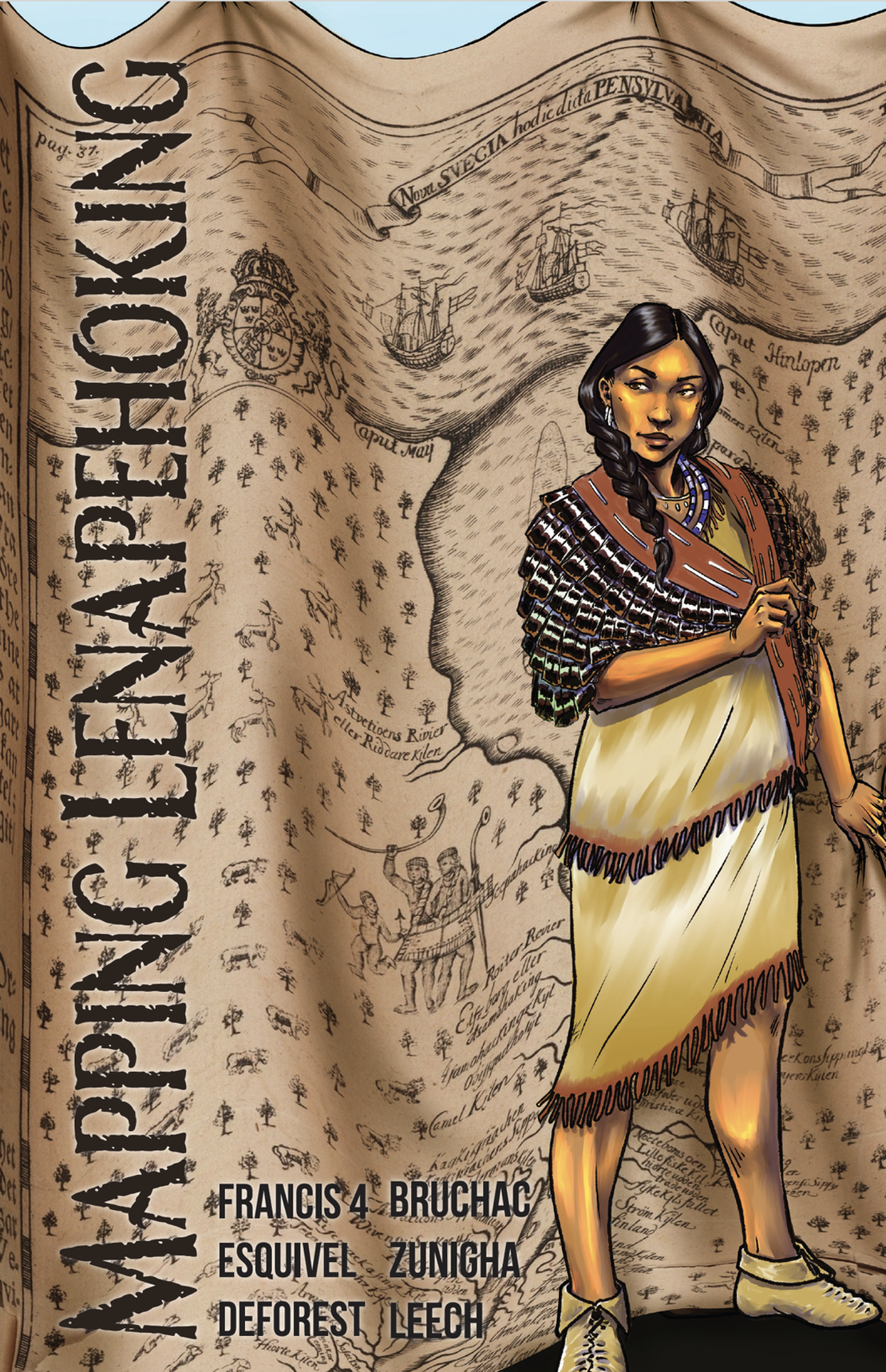

The greater Philadelphia area, which includes parts of present-day eastern Pennsylvania, southern New Jersey, and northern Delaware, has a population of more than six million people, the vast majority of whom are not Indigenous to this place. Before European colonizers arrived in the 1600s, Indigenous people were in control of this region, which they called Lenapehoking. Eventually, the Lenape came to be known as “Delaware Indians,” a name that intertwines with settler-colonial occupation of this place. Here, as elsewhere across the continent, the removal of Indigenous people from their lands, and the loss of tribal names for those places, served as forms of historical erasure, aided and abetted by the widespread use of colonizer’s words. When did this European name for the Lenape come into use? Why “Delaware”? The process of answering these questions illuminates the lingering impacts of colonial influences in naming and renaming Indigenous people. Yet, despite the use of colonial names as tools of dispossession, these names can, in some cases, become important markers of Indigenous survivance and sovereignty.

Lenape and the First European Arrivals

Oral traditions and archaeological evidence date the occupation of Lenapehoking as far back as the last glacial period, roughly 10,000 years ago.1 Traditionally, the Indigenous people of this region called themselves Lenni Lenape (lə̀ni-ləná·p·e, roughly translating to “real person”) or simply Lenape.2 Other Northeastern Native peoples often refer to the Lenape as “ancient ones” or “grandfathers,” reflecting their role as diplomats among other Native nations, and their history as one of the first Native groups to interact with European colonists.3 Before those colonists arrived, the present-day “Delaware River” was known as Lenapewhittuck (meaning “river of the Lenape”).4

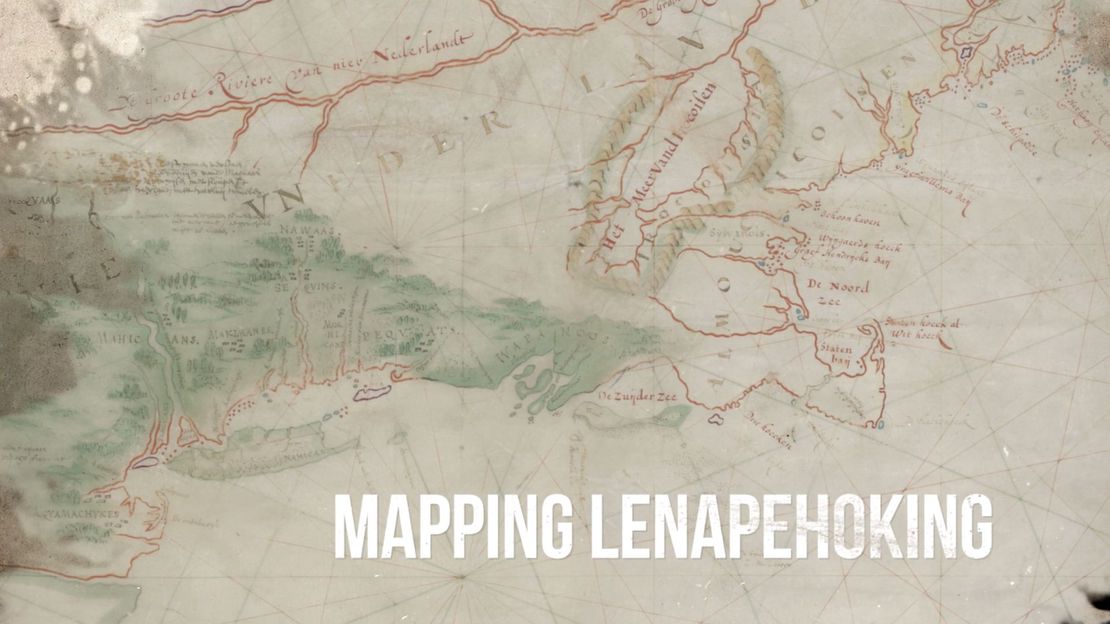

One of the earliest European explorers in the region was Henry Hudson, whose 1609 voyage into New York Bay on behalf of the Dutch East India Company gave the Dutch a rationale to attempt to claim the land.5 Early maps were highly speculative, but two Dutch mapmakers – Hensel Gerritsz and Johannes de Laet – created accurate maps of the area’s coastline, using data in Hudson’s journals.6 These and other colonial maps, however, diminished the size of Lenape territory; instead of reaching across the river and eastward to the Atlantic, it was misconstrued as being just a small area of land surrounding the river.7 The impression that the Lenape homeland was small (and that vast areas were empty) provided justification for colonists to begin to exert control over the land, beginning with new place names.8 The Dutch used several different names for the river, including: “Zuyd Rivier” (“south river,” relative to the Hudson, called “north river”), “Nassau River,” “Prince Hendrick River,” and “Charles River.” The Swedish settlers called it “New Swedeland stream.”9

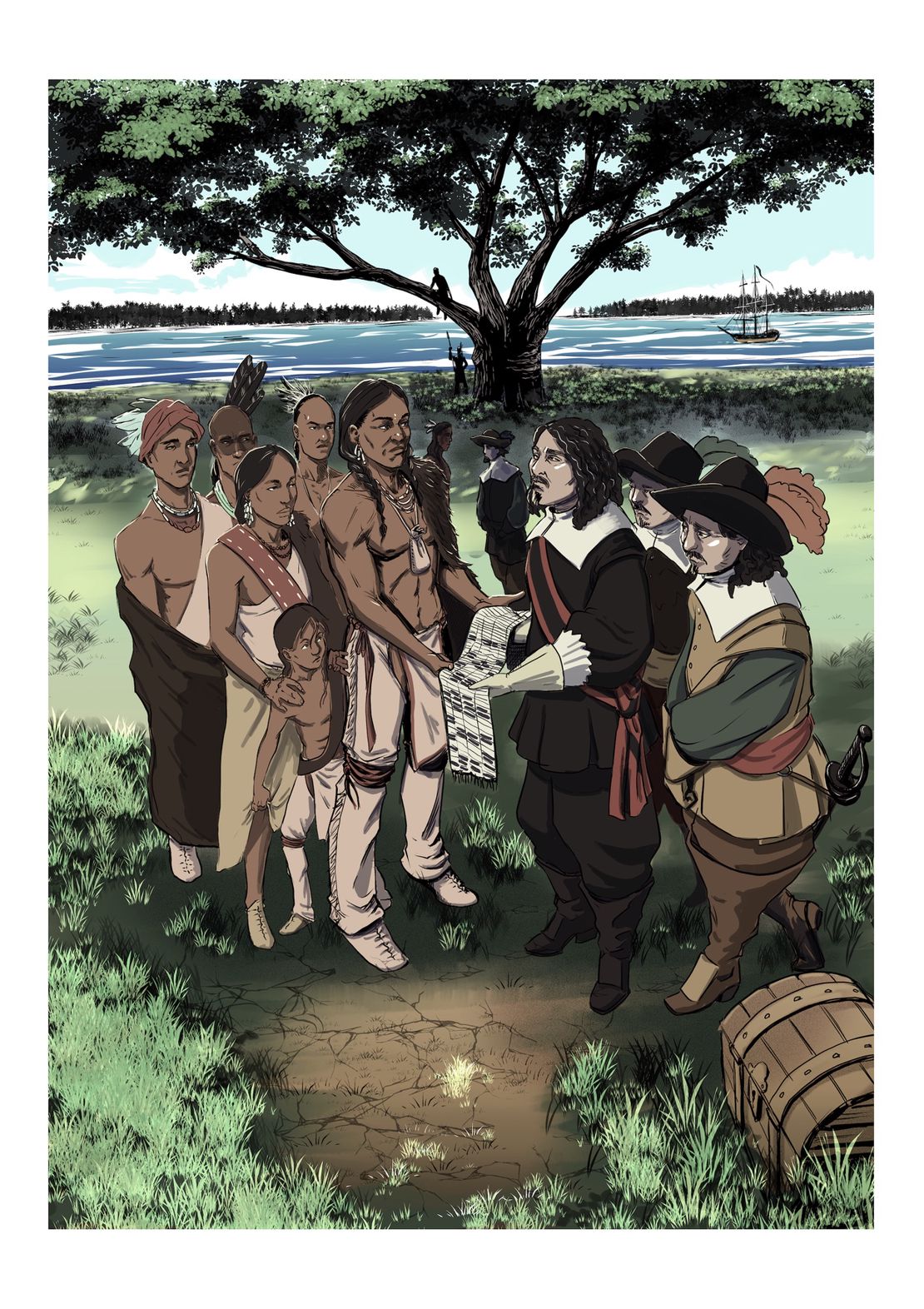

During the 1620s-1630s, small colonies of Dutch, Swedish, and Finnish settlers initiated trade with the Lenape, while settling “New Netherlands” and “New Sweden.”10 Initially, the Lenape remained in control of the territory, setting terms and conditions for European trade and settlement.11 But during the 1670s, as colonists increased in number, and introduced disease and alcohol, Lenape populations began to decrease.12 In 1682, a colony of English religious separatists – members of the Society of Friends (Quakers) – settled the region, led by William Penn, the namesake for the colony and state of Pennsylvania.13 These colonists routinely referred to the Lenape as “Delaware.” But where did this new name come from? To answer that question, we need to look back at the history of the Virginia Colony, several decades earlier.

Baron De La Warr and the Re-naming of Lenapewhittuck

In 1606, Thomas West (1576-1618), the twelfth Baron De La Warr from Hampshire, England, was appointed by King James I to the council overseeing the Virginia Company of London. He served as the first English Governor of the Colony of Virginia, and was noted for establishing a “strict, military-like regime” and a “brutal campaign against the Indians.”14 Ironically, even though several counties, a state, a bay, and a river are named after him, De La Warr (pronounded de-lah-ware) never laid eyes on most of this territory. He left in 1611 and never returned, but his impact persists in the names left on the landscape.15

Over the next few decades, De La Warr’s name, in the English form of “Delaware,” started to appear on maps of Lenape territory, replacing Dutch names.16 In Gerritsz and de Laet’s 1630 Dutch map, the river is labeled as “Zuyd Rivier” (“south river”).17 A map created by David Pietersz DeVries in the same year identifies the river’s outlet as “Zuid-Baai” (“south bay”).18 Most maps from this era show the persistence of Dutch names in examples like “R. de Sud” (“south river” in French).19 But a 1631 map by French cartographer Jean Guerard (the earliest instance of any variation of “Delaware” on a map) identifies the bay as “Dellowar Bay.”20 Two decades later, in 1651, a map by Virginia Company’s John Farrer identifies the river as “Delawar’s River.21 After 1660, the bay was consistently labeled Delaware, indicating that the river was likely called Delaware as well. For example, an English map of New Jersey, published by John Thornton in 1706, includes the designation “Dellewar Bay.”22

How, then, did the name “Delaware” come to be given to not just the river and bay, but the Lenape people as well? It has largely to do with the concept of exonyms, defined as names “used by outsiders to refer to an ethnic, racial, or social group or its language that the group itself does not use.”23 Essentially, exonyms rename people and places in foreign languages; this phenomenon, seen around the world, is especially pronounced in North America. When the name “Delaware River” caught on during the mid-1600s, Lenape bands living near the Lenapewhittuck began to be referred to as “Indians from the Delaware Valley.” Soon, “Delaware” became an adjective: “Delaware Indians,” applied to virtually all Lenape peoples.24 Lenape people also began to use this name for themselves, reflecting a pattern among other East Coast Indigenous communities, who would introduce themselves by identifying the “place to which they belonged,” even when this was not their tribal name.25

The Legacies of Naming and Renaming

By the mid-1700s, as Lenape people began shifting westward to escape the pressures of colonial settlement, the name Delaware was more frequently used, as both a descriptor of their origins the mid-Atlantic region, and a blanket term to lump multiple bands of Native people together.26 Although, traditionally, Indigenous people would not have contained themselves within the categories put upon them by Europeans, they claim their present-day tribal names as evidence of their survivance and sovereignty. In essence, the adoption of new names was out of necessity, more than choice, as a means to survive in the face of settler-colonial pressures. And so, Lenape people today have embraced the name Delaware.

By adapting to the constraints forced upon them by colonial governments, the Lenape continued to survive, even after being displaced over 1,400 miles from their homelands.27 The name Delaware, which was densely recorded in state and federal records, documented the depth of their history, and informed their petitions for federal recognition, confirming the existence “natiof on-to-nation relationships” within the bounds of the United States.28 Today, Lenape people are known by the federal governments of the United States and Canada under new names: “Delaware Nation” (Anadarko, OK), “Delaware Tribe of Indians” (Bartlesville, OK), and “Delaware of Six Nations” (Brantford, ON). Two bands have retained their Munsee name: “Stockbridge-Munsee Community” (Bowler, WI), and “Munsee-Delaware Nation” (St. Thomas, ON). One band still bears the name of the missionary group that converted them: “Moravian of the Thames First Nation” (Chatham-Kent, ON).29

Despite centuries of dispossession and removal, Lenape people continue to survive, having carried their kin and culture with them into new homelands. Yet, they still hold deep emotional connections to their home territory of Lenapehoking. As Lenape knowledge-keeper Curtis Zunigha explains: “Land was the first and foremost means of dispossession. We are not people who merely live on the land; we are of the land. . .By removing the people from the land, you lose the source of who we are.”30

Sources Cited:

Barber, Edwin A. 1884. “Notes on the Lenni Lenápe, or Delaware Indians, of Pennsylvania,” The American Antiquarian and Oriental Journal 6 (6) (1884): 385-389.

Bridenbaugh, Carl. 1976. “The Old and New Societies of the Delaware Valley in the Seventeenth Century.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 100 (2) (April 1976): 143-172.

Brooks, Lisa. 2018. Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

De Vries, David Pietersz. 1630. De Zuid-Baai in Nieuw Nederland. Reprinted in Korte historiael, ende journaels aenteyckeninge, van verscheyden voyagiens in de vier deelen des wereldts-ronde, als Europa, Africa, Asia, ende Amerika gedaen. Brekegeest, Netherlands: Symon Cornelisz 1655. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100240404

Delaware Tribe of Indians. “About the Delaware Tribe of Indians,” Delaware Tribe of Indians. Accessed November 12, 2023 on-line at: https://delawaretribe.org/home-page/about-the-tribe/#:~:text=The%20name%20%20DELAWARE%20was%20%20given,to%20almost%20all%20%20Lenape%20%20people.&as_qdr=y15

Donehoo, George P. 1928. A History of the Indian Villages and Place Names in Pennsylvania. Harrisburg, PA: The Telegraph Press. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/007043706

Dunlap, Arthur Ray. 1945. “A Checklist of Seventeenth-Century Maps Relating to Delaware.” Delaware Notes. 18th Series. Newark, NJ: University of Delaware 1945: 63-76. https://udspace.udel.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/3e8c3b6c-a2dd-4450-9fda-12b60ed80b56/content

Dunlap, Arthur Ray and Carl A. Weslager. 1967. “Two Delaware Valley Indian Place Names.” Names: A Journal of Onomastics 15 (3) (1967): 197-202.

Dunn, Richard S. “William Penn and the Selling of Pennsylvania, 1681-1685.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 127 (5) (October 1983): 322-329.

Duval, Pierre. 1653. Le Canada faict par le Sr. de Champlain, ou, sont, La Nouvelle France, la Nouvelle Angleterre, la Nouvelle Holande, la Nouvelle Svede, la Virginie &c. avec les nations voisines et autres terres nouvellement decouvertes suivant les memoires de P. du Val, géographe du Roy. “Gallica.” Bibliothèque nationale de France. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8493428x

Farrer, John. 1651. A mapp of Virginia discovered to ye hills, and in it’s latt. from 35 deg. & 1/2 neer Florida to 41 deg. bounds of New England. Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3880.ct000903/

Fur, Gunlög. 2011. A Nation of Women: Gender and Colonial Encounters Among the Delaware Indians. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Futhey, John Smith and Gilbert Cope. 1881. History of Chester County, Pennsylvania, with Genealogical and Biographical Sketches. Philadelphia, PA: L. H. Everts. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/012288592

Gerritsz, Hessel and Johannes de Laet. 1630. Nova Anglia, Novvm Belgivm et Virginia. In “Charting New Netherland, 1597-1682.” New Netherland Institute. https://www.newnetherlandinstitute.org/history-and-heritage/digital-exhibitions/charting-new-netherland-1600/the-maps/nova-anglia-novum-belgium-et-virginia-1630

Guerard, Jean. 1631. Carte [de l’Océan Atlantique]. “Gallica.” Bibliothèque nationale de France. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b55007067q

Heckewelder, John and Peter S. Du Ponceau. 1834. “Names Which the Lenni Lenape or Delaware Indians, Who Once Inhabited This Country, Had Given to Rivers, Streams, Places.” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society Vol. 4 (1834): 351-396.

Herrman, Augustine, 1670. Virginia and Maryland as it is planted and inhabited this present year 1670. Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3880.ct000766/?r=-0.38,-0.187,1.852,1.125,0

Kraft, Herbert. 1987. The Lenape: Archaeology, History, and Ethnography. Newark, NJ: New Jersey Historical Society.

Norwood, John R. 2007. We Are Still Here! The Tribal Saga of New Jersey’s Nanticoke and Lenape Indians. Moorestown, NJ: Native New Jersey Publications. https://nanticoke-lenape.info/images/We_Are_Still_Here_Nanticoke_and_Lenape_History_Booklet_pre-release_v2.pdf

Obermeyer, Brice. 2009. Delaware Tribe in a Cherokee Nation. Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press.

Rose, E. M. 2020. “Lord Delaware, First Governor of Virginia, ‘the Poorest Baron of this Kingdom.’” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 128 (3) (2020): 226-258.

Scharf, John T. 1888. History of Delaware: 1609-1888. Philadelphia, PA: L. J. Richards.

Soderlund, Jean R. 2015. Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society Before William Penn. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Thornton, John. 1706. A new mapp of East and West New Jarsey: being an exact survey. Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3810.ct000064/?r=0.067,0.124,0.372,0.226,0

Virginia Humanities Council. no date. “Thomas West twelfth baron De La Warr (1576–1618),” Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/west-thomas-twelfth-baron-de-la-warr-1576-1618/

Wermuth, Thomas, et al. no date. “The Twin Mysteries of Henry Hudson—His 1609 Voyage,” Hudson River Valley Institute. Accessed November 27, 2023 on-line at: https://www.hudsonrivervalley.org/the-twin-mysteries

Weslager, Carl A. 1949. “The Indians of Lewes, Delaware, and an unpublished Indian deed dated June 7, 1659.” Bulletin Archaeological Society of Delaware 4 (5) (January 1949): 6-14.

Zeisberger, David. 1827. Grammar of the language of the Lenni Lenape or Delaware Indians. Translated by Peter Stephen Du Ponceau. Philadelphia, PA: J. Kay. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100769161

Zunigha, Curtis. 2023. “Forced Removals of Lenape: The Original People.” In A Lenapehoking Anthology, edited by Hadrien Coumans, Joe Baker, and Joel Whitney, pp. 41-59. New York, NY: The Lenape Center and Brooklyn Public Library.

Curtis Zunigha, “Forced Removals of Lenape: The Original People,” in A Lenapehoking Anthology, edited by Hadrien Coumans, Joe Baker, and Joel Whitney (New York, NY: The Lenape Center and Brooklyn Public Library 2023), 41. Also see Richard Veit, “Setting the Stage: Archaeology and the Delaware Indians, a 12,000-Year Odyssey,” in New Jersey: A History of the Garden State, edited by Maxine N. Lurie and Richard Veit (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2012), 11. ↩︎

The Lenape Talking Dictionary, accessed November 30, 2023. Also see David Zeisberger, Grammar of the language of the Lenni Lenape or Delaware Indians, translated by Peter Stephen Du Ponceau (Philadelphia, PA: J. Kay 1827). There are two distinct dialects of the language: Unami for the southern parts of Lenape territory, and Munsee for the north; see Herbert Kraft, The Lenape: Archaeology, History, and Ethnography (Newark, NJ: New Jersey Historical Society 1986). ↩︎

John R. Norwood, We Are Still Here! The Tribal Saga of New Jersey’s Nanticoke and Lenape Indians, (Moorestown, NJ: Native New Jersey Publications 2007), 10. Also see Gunlög Fur, A Nation of Women: Gender and Colonial Encounters Among the Delaware Indians (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011). ↩︎

On the name of the river, see John Heckewelder and Peter S. Du Ponceau, “Names Which the Lenni Lenape or Delaware Indians, Who Once Inhabited This Country, Had Given to Rivers, Streams, Places,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society Vol. 4 (1834), 355. ↩︎

Thomas Wermuth et al, “The Twin Mysteries of Henry Hudson—His 1609 Voyage,” Hudson River Valley Institute. ↩︎

Hessel Gerritsz and Johannes de Laet, Nova Anglia, Novvm Belgivm et Virginia (1630), “Charting New Netherland, 1597-1682,” New Netherland Institute. ↩︎

Fur, A Nation of Women, Chapter 4. Also see “Lenapehoking (Lenni-Lenape),” Native Land Digital. ↩︎

Richard S Dunn, “William Penn and the Selling of Pennsylvania, 1681-1685,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 127 (5) (October 1983): 322-329. ↩︎

Edwin A Barber, “Notes on the Lenni Lenápe, or Delaware Indians, of Pennsylvania,” The American Antiquarian and Oriental Journal 6 (6) (1884), 385. Also see John Smith Futhey and Gilbert Cope, History of Chester County, Pennsylvania, with Genealogical and Biographical Sketches (Philadelphia, PA: L. H. Everts 1881), 9. ↩︎

Carl Bridenbaugh, “The Old and New Societies of the Delaware Valley in the Seventeenth Century,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 100 (2) (April 1976): 143-172. ↩︎

Jean R. Soderlund, Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society Before William Penn (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press 2015), Chapter 4. ↩︎

Bridenbaugh, “The Old and New Societies,” 160. ↩︎

Soderlund, Lenape Country, Chapter 4. ↩︎

Virginia Humanities Council, “Thomas West twelfth baron De La Warr (1576–1618),” Encyclopedia Virginia. ↩︎

E. M. Rose, “Lord Delaware, First Governor of Virginia, ‘the Poorest Baron of this Kingdom’,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 128, no. 3 (2020), 228, 236. ↩︎

For a list of early maps, see Arthur Ray Dunlap, “A Checklist of Seventeenth-Century Maps Relating to Delaware,” Delaware Notes 18th Series (Newark, NJ: University of Delaware 1945): 63-76. ↩︎

Hessel Gerritsz and Johannes de Laet, Nova Anglia, Novvm Belgivm et Virginia (1630), “Charting New Netherland, 1597-1682,” New Netherland Institute. ↩︎

David Pietersz De Vries, De Zuid-Baai in Nieuw Nederland (1630), reprinted in Korte historiael, ende journaels aenteyckeninge, van verscheyden voyagiens in de vier deelen des wereldts-ronde, als Europa, Africa, Asia, ende Amerika gedaen (Brekegeest, Netherlands: Symon Cornelisz 1655). For discussion of De Vries and the Lewes Colony, see Carl A. Weslager, “The Indians of Lewes, Delaware, and an unpublished Indian deed dated June 7, 1659,” Bulletin Archaeological Society of Delaware 4 (5) (January 1949): 6-14. ↩︎

Pierre Duval, Le Canada faict par le Sr. de Champlain, ou, sont, La Nouvelle France, la Nouvelle Angleterre, la Nouvelle Holande, la Nouvelle Svede, la Virginie &c. avec les nations voisines et autres terres nouvellement decouvertes suivant les memoires de P. du Val, géographe du Roy (1653), “Gallica,” Bibliothèque nationale de France. ↩︎

Jean Guerard, Carte [de l’Océan Atlantique] (1631), “Gallica,” Bibliothèque nationale de France. ↩︎

John Farrer, A mapp of Virginia discovered to ye hills, and in it’s latt. from 35 deg. & 1/2 neer Florida to 41 deg. bounds of New England (1651), Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress. ↩︎

John Thornton, A new mapp of East and West New Jarsey: being an exact survey (1706), Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress. ↩︎

“Exonym,” Dictionary.com. ↩︎

“About the Delaware Tribe of Indians,” Delaware Tribe of Indians. Also see John T. Scharf, History of Delaware: 1609-1888 (Philadelphia, PA: L. J. Richards, 1888), 10-13. ↩︎

Lisa Brooks, Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018), 9. ↩︎

Brice Obermeyer, “Removal and the Cherokee-Delaware Agreement,” in Delaware Tribe in a Cherokee Nation (Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press 2009), 37-48, 52-58. Excerpted as “Removal History of the Delaware Tribe,” Delaware Tribe of Indians. ↩︎

Curtis Zunigha, “Forced Removals of Lenape: The Original People.” ↩︎

U.S. Department of the Interior, Federal Tribal Recognition, July 12, 2012. ↩︎

“Tribal Directory,” National Congress of American Indians, accessed November 30, 2023 on-line at: https://www.ncai.org/tribal-directory?letter=D ↩︎

Curtis Zunigha, personal communication in an interview, November 29, 2023. ↩︎