Abstract

This essay retraces historical Lenape place names and movements by analyzing a series of archival maps and written accounts from 1756 to 1813. It expands upon Clinton A. Weslager’s Delaware Indian Westward Migration, (1978), which charted some of the major forced movements of Lenape communities from their ancestral homelands known as Lenapehoking (encompassing parts of today’s eastern Pennsylvania, northern Delaware, New Jersey, southern New York, and a portion of western Connecticut) to places as far away as present-day Oklahoma, Kansas, and Ontario. This study explores the relationships among Lenape dispossessions, archival maps, and written colonial documents featuring Lenape voices. When read together, these sources provide insight into how Lenape people navigated and criticized colonial settler dispossessions. By re-mapping these historic relocations through the archival record, this work emphasizes the persistence of Lenape cultural histories on the landscape, both within and beyond their ancestral homeland.

In 1978, historian Clinton A. Weslager published Delaware Indian Westward Migration, a book that retraces the major paths of forced Lenape migrations across North America from the late seventeenth to early nineteenth century. The area encompassing today’s eastern Pennsylvania, northeastern Delaware, New Jersey, southern New York, and a small portion of western Connecticut is the ancestral homeland of Lenape peoples, who may also identify as Delaware or Munsee. This homeland is known as Lenapehoking, from Lënapehòkink, meaning “Land of the Lenape.”1 The historic dispossession of Lenape people was not a singular mass movement; rather, Lenape individuals and families relocated in small groups over time (sometimes moving back and forth multiple times), making population estimates difficult. Weslager’s map suggests the paths or waterways these Lenape groups followed and documents the formation of new Lenape towns in western “Indian Territory,”2 where Lenape refugees formed new communities, joined Moravian missions, or merged with other Native groups. Weslager’s archival research culminated in a new map depicting the major movements of Lenape (or Delaware) people to present-day Western Pennsylvania, Ohio, Missouri, Kansas, and Oklahoma (see fig. 1).

Figure 1. Migrations of the Delaware Indians, in C. A. Weslager, The Delaware Indian Westward Migration: With Texts of Two Manuscripts, 1821–22, Responding to General Lewis Cass’s Inquiries about Lenape Culture and Language (New Castle: Middle Atlantic Press, 1978), 231.

Despite the breadth of Weslager’s archival research, his account lacks archival maps documenting these historic relocations. While more recent scholars have updated the continental map of Lenape diasporic movements,3 further work is needed to explore the relationships among Lenape dispossessions, archival maps, and colonial documents featuring Lenape voices. This article brings together a chronological series of colonial maps and contemporaneous archival accounts, as a means to recover Lenape histories, even within documents that were themselves tools of dispossession. Toponyms (place names) from each map are listed—many of these names can be connected to Lenape history, and still appear on contemporary maps today.

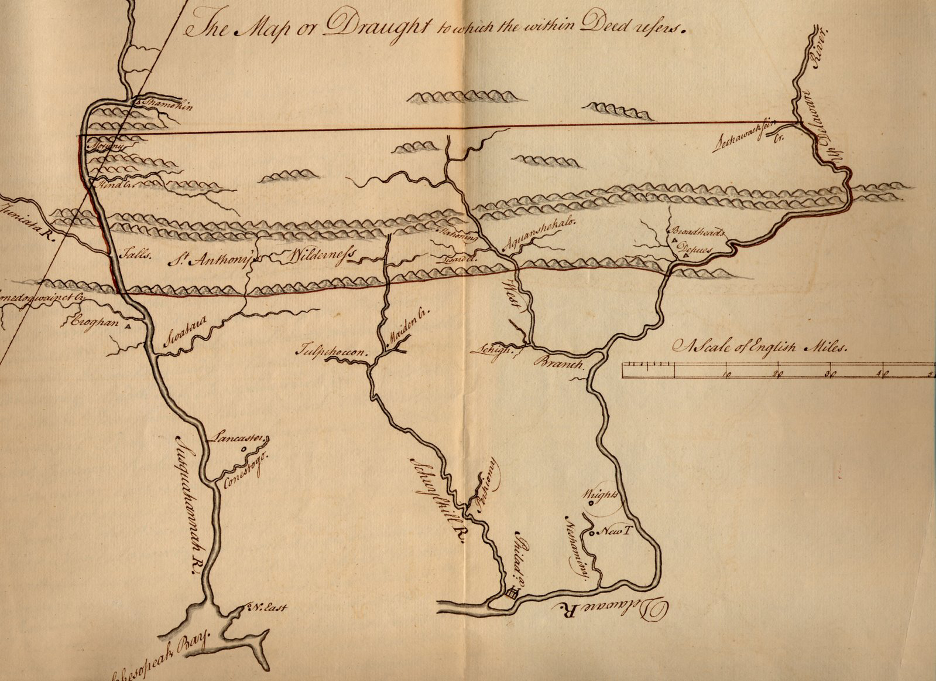

Figure 2. Map made after the Treaty at Easton, 1756, in Chew Family Papers, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

By the early 1800s, a century of settler invasions by Dutch, Swedish, and English colonists had already forced Lenape people to relocate to the forks of the Delaware River and the Lehigh River, among other locations, displaced by colonial violence. Following the fraudulent Walking Purchase of 1737, Lenape people were dispossessed of much of their ancestral homeland in eastern Pennsylvania and across New Jersey. During the negotiations that followed the Treaty of Easton in 1756 (see fig. 2), for example, the 3,044-acre Brotherton Reservation was created in Burlington County, New Jersey.4

The Lenape leader Teedyuscung (1700–1763) played a prominent role in negotiations with the Pennsylvania colonial government. Teedyuscung began the Condolence Ceremony at the Treaty of Easton on November 13, 1756, in a traditional manner, by “metaphorically wip[ing] tears from Pennsylvanians’ eyes and blood from their bodies and from the ground…[before] he then proceeded to talk about the origins of the war.”5 Teedyuscung recalled positive relations with William Penn but decried the recent deceit of the colonial government. Addressing Governor William Denny, he declared, pounding his foot: “this very ground that is under me was my land and inheritance, and it is taken from me by fraud.” Teedyuscung then detailed the lands that had been improperly seized by the perpetrators of the Walking Purchase: “When I say this ground, I mean all the land between Tohiccon Creek and Wyoming on the Susquehanna.” 6 According to historian James H. Merrell, Teedyuscung, who had several years of experience dealing “with clerks and copies, with translators and transcripts… blamed the conflicts between natives and newcomers on scribes.” 7 When Teedyuscung revisited Easton shortly before his death, he remarked: “‘Somebody must have wrote wrong… and that makes the Land all bloody.’”8

Teedyuscung’s criticisms of the Walking Purchase are among the most well-known, but many other Lenape people contested settler encroachment during this period. Records of many Lenape place names (toponyms) from this region first appear in writing in the form of legal challenges made by Lenape individuals against Pennsylvania’s colonial government. For example, Mahoning in today’s Carbon County, Pennsylvania (from mahóni, “a deer lick,” and mahonink, “at the lick,” depicted in figure 2) first appears in a November 12, 1740, letter expressing the Lenape’s belief that they were being wrongfully removed from lands that did not fall “within the limits of the Walking Purchase.” 9

Toponyms: Perkiomy (elsewhere Perkioming, from pakihm-omeak, “the cranberry place” or pakiomink, “the place where the cranberries grow” now known as the Perkiomen River; Tulpehoccon (from tûlpewihacki, “the land abounding with turtles, turtle country” or tulpehaking, “turtle land”); Neshaminy (from neshâmhanne, “two streams making one”); Lehigh (from lěcháwâk, “fork,” as in a parting of roads or streams); Mahoning (from mahóni, “a deer lick,” and mahonink, “at the lick”); Aquanshekalo (elsewhere Aquashicola, from achquonschícola, “the brush net fishing creek, the creek where we catch fish by means of a net made with brush”); Lechawacksein Cr. (elsewhere Lackawaxan, from lechauweksink, “the forks of the road, or the part of the road” or eenda lxawahkwsiing, “where there is a forked tree… where there are forked trees”); Shamokin (from shahamóki, shahamókink, and schacheméki, “the place of eels”).10

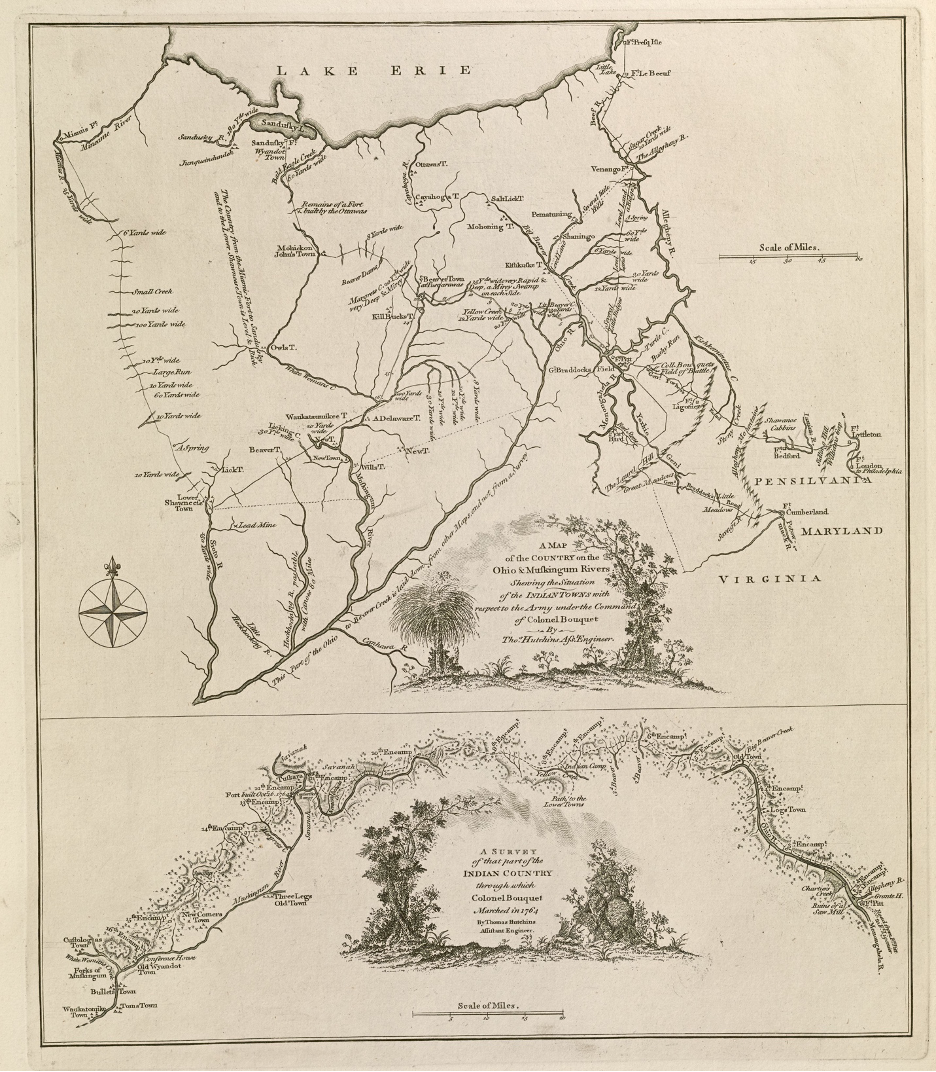

Figure 3. A map of the country on the Ohio and Muskingum Rivers: Shewing the situation of the Indian towns with respect to the army under the command of Colonel Bouquet, by Thomas Hutchins (1730–1789) London: Printed for Robert Sayer and Thomas Jefferys, 1764. Map reproduction courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library.

During the Seven Years’ War (also known as the French and Indian War, 1754–63), many Lenape people relocated from Western Pennsylvania to Tuscarawas country in today’s Ohio. The largest Delaware community here, home to about 600–700 people, was Gekelmukpechunk (“The water that is always still”), founded by the Delaware leader Netawatwees (1686–1776). As the above map shows (see fig. 3), Gekelmukpechunk was also called “Newcomerstown,” in reference to Netawatwees’s nickname, “Newcomer.” This name persists to the present in Tuscarawas County.11

In 1764, surveyor and military engineer Thomas Hutchins (1730–1789) charted Newcomerstown on his map of the region spanning Lake Erie and the Ohio River. Colonel Bouquet (whose army is referenced on the map) led a party of troops into Ohio Country with the goal of stopping the pan-Indian uprisings later known as Pontiac’s Rebellion. Pontiac, an Ottawa leader in the Great Lakes region, was likely inspired by the Delaware prophet Neolin (“the enlightened one”). In 1760, a French colonist recorded Neolin’s speech, which reads, in part:

Whence comes it that ye permit the Whites upon your lands? Can ye not live without them?…Ye could live as ye did live before knowing them—before those whom ye call your brothers had come upon your lands… But when I saw that ye were given up to evil, I led the wild animals to the depths of the forest so that ye had to depend upon your brothers to feed and shelter you. Ye have only to become good again and do what I wish, and I will send back the animals for your Food… But as to those who come to trouble your lands—drive them out, make war upon them. I do not love them at all; they know me not, and are my enemies, and the enemies of your brothers. Send them back to the lands which I have created for them and let them stay there.12

These remarks show the importance of Indigenous self-determination after nearly two centuries of alienation and forced removals from their homelands. In 1774, Lenape people left Gekelmukpechunk and established a new community they called Coshocton on the site of a former Wyandot village by the Forks of the Muskingum River. This remained a key settlement for Ohio Delawares until April 19, 1781, when Colonel Daniel Brodhead and his troops set fire to the town and murdered several captive prisoners. Despite this devastating loss, the Delaware—along with other Indigenous allies—continued to resist American encroachment, successfully defending their lands in battles against American troops in 1789 and 1791. However, their efforts culminated in a hard-fought defeat at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794, where Delaware fighters, led by Miami leader Little Turtle and Shawnee leader Blue Jacket, were ultimately overcome. They, along with many other Native Nations, signed the 1795 Treaty of Greenville, which forced the Delaware to give up the majority of their land in present-day Ohio.13 In 1802, colonial settlers established “Tuscarawastown” at the former site of Coshocton; the Lenape name was restored in 1811, when the town became the county seat of the newly established Coshocton County.14

Toponyms: Waukatatumikee (Waukatomike) Town; Custologas Town (the name of a Delaware leader); Old Wyandot Town; New T., NewTown, NewComers Town; Three Legs Old Town; Mahoning (from mahoni, salt lick); Beaver T.; “A Delaware Town;” Muskingum River; Lower Shawneetown; Hockhocking River (“place of bottle gourds”); Little Hockhocking River; Nemenshehela Creek (elsewhere Nimishellin); Indian Camp; Yellow Creek; Old Town; Longs Town; Monongahela River; Kishkustke T., Cayahoga T.; Mohickon John’s Town (inhabited from 1760–1778 by refugee Mohican, Delaware and Stockbridge peoples).15

![Figure 4. A map of the province of Upper Canada, describing all the new settlements, townships, &c.: with the countries adjacent, from Quebec to Lake Huron (original and cropped detail), by David William Smyth (1764–1837), London: William Faden (1749–1836), 2nd ed. 1813 [orig. pub. 12 April 1800], McMaster University: Hodsoll Collection Digital Archive.](/images/content/LeechM001/image6.jpeg)

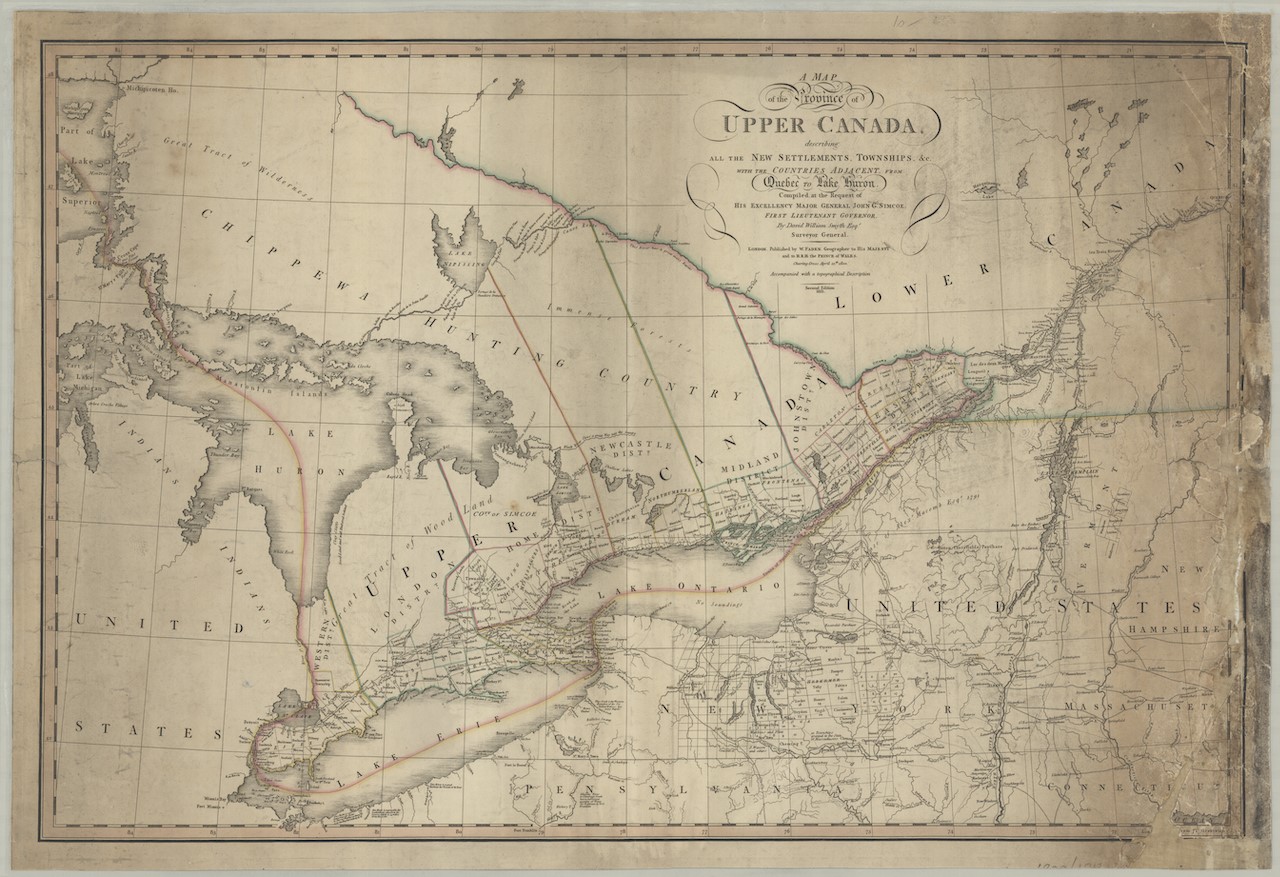

Figure 4. A map of the province of Upper Canada, describing all the new settlements, townships, &c.: with the countries adjacent, from Quebec to Lake Huron (original and cropped detail), by David William Smyth (1764–1837), London: William Faden (1749–1836), 2nd ed. 1813 [orig. pub. 12 April 1800], McMaster University: Hodsoll Collection Digital Archive.

Another major diasporic movement during the late eighteenth century was the path of Christianized Moravian Lenape people. Pressed by colonial and inter-tribal violence from warring factions across Ohio, a sizeable number of Lenape people chose to join Moravian Missions from 1740 to 1815, including Schoenbrunn, Gnaddenhutten, and Lichtenau. In 1792, 150 Delaware Indians, alongside the Moravian missionary David Zeisberger (1721–1808), left Ohio and resettled along what is now called the Thames River in today’s southwestern Ontario, where they established a town called “Schonfeld” (Fairfield). The Moravian Lenape community petitioned for this land based on a 1790 treaty also signed by leaders of the Chippewas, Ottawas, Potawatomies, and Hurons.16

An 1813 map (see fig. 4) includes the toponyms “Delewars” and “Chippewa” in a cluster below the town of London, Ontario, not far from Lake Erie. During the War of 1812, a combined force of Indigenous First Nation and British allied forces led by Chief Tecumseh held off American troops at the Battle of the Thames (October 5, 1813), despite being greatly outnumbered.17 Tecumseh was mortally wounded in this battle, and the American troops destroyed Fairfield. After the Peace of 1814, the Moravian Indian community reestablished their settlement as “New Fairfield” on the opposite side of the Thames River. Today, the area that once encompassed New Fairfield is known as Moraviantown, and a small portion of this land is home to the Lenape (Lunaapeew) People of the Delaware Nation at Moraviantown; their nineteenth-century mission house and church are still standing.18

Although his words are filtered through a settler perspective, Zeisberger’s journal records how some Delaware people reflected upon the hardships they endured when defending their lands from the United States government:

Wednesday, 15 [October] 1794

Chippewa and Delaware Indians arrived [at Fairfield on the Thames] from the Miami. There are general disturbances among the Indians and want of unity. The Delaware fully intend to leave this part of America, and to flee to the south and New Spain, but are not all agreed about this, but some go away secretly and come here. They have spoken the truth straight out to their fathers, namely: “Thou hast always hitherto urged us to go to war against the States. We have followed thee to our great loss. Look at the graves on the Miami, look farther on, where the bones of the young folk lie, you whom the beasts have fed. Thou art the cause of their death. Thou hast always preached to us and said: ‘Behold, the States are taking away your land. Be brave, act like men. Let not your land be taken from you. Fight for your land.’ But now we have got at the truth. The States have struck thee to the ground and overcome thee. Therefore hast thou given them our land in order to have peace from them, but thou tellest us to fight for it, so that we may all be blotted out… Thou mayest carry on war alone. We will no longer be deceived by thee.”19

Toponyms: Shawanese Township; Moravian Village; Delaware; “Delewars,”; Chippewas.

Conclusion

These cartographic traces and archival fragments offer glimpses into Lenape experiences, but they by no means tell a complete story. Colonial documents are, by their very nature biased, partial, and problematic records; Native place names are often approximations inscribed on maps and deeds by colonists who sought to appropriate Indigenous lands. Military officers and government officials mapped the locations of newly formed Lenape towns, like “Newcomerstown,” as conflicts between settler and Native communities worsened. Stitched together, these episodic accounts show how Lenape people responded to dispossession. Importantly, Lenape voices, experiences, and histories of place over nearly two centuries of forced relocations are not lost; they resonate in social memory, in the colonial archive, and on the landscape itself, within and beyond their ancestral homeland.

Although settler perspectives are amplified within dominant historical narratives, they are deeply intertwined with the Native histories resonate throughout the colonial archive. Native leaders like Teedyuscung openly accused English settlers of defrauding Lenape people after the deceitful Walking Purchase of 1737. The Delaware prophet Neolin shaped a major pan-tribal movement that advocated for Indigenous self-determination and decried the violence of settler dispossessions. As Lenape people were pushed further from their ancestral home, they told new stories and established new place names, like Coshocton in present-day Ohio. Across the United States and Canada, Lenape place names and their approximations represent deep and enduring worlds of meaning that persist despite colonial erasures. Their prevalence underscores both the Lenape’s profound connection to the land and the histories of their dispossession. It is past time that these histories be acknowledged in their full scope, both on and beyond the settler maps where their traces can be still followed.

Bibliography

Baker, Joe, Hadrien Coumans, and Joel Whitney, eds. Lenapehoking: An Anthology. New York: Lenape Center & Brooklyn Public Library, 2022.

Chew, Benjamin. Map from Treaty at Easton. 1762. Benjamin Chew Family Papers [2050], Box 42, Folder 4, Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, PA. Accessed June 1, 2024. https://discover.hsp.org/Record/dc-6299.

Grumet, Robert S. Beyond Manhattan: A Gazetteer of Delaware Indian History Reflected in Modern-Day Place Names. Albany: New York State Museum, 2014.

Grumet, Robert S. Manhattan to Minisink: American Indian Place Names of Greater New York and Vicinity. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013.

Hutchins, Thomas. A map of the country on the Ohio and Muskingum Rivers: shewing the situation of the Indian towns with respect to the army under the command of Colonel Bouquet. London: Printed for Robert Sayer and Thomas Jefferys, 1764. Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library, Boston, MA. Accessed June 1, 2024. https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:q524n480v.

Merrell, James H. “‘I Desire All That I Have Said… May Be Taken down Aright’: Revisiting Teedyuscung’s 1756 Treaty Council Speeches,” The William and Mary Quarterly 63, no. 4 (2006): 777–826.

Navarre, Robert. Journal of Pontiac’s Conspiracy, edited by M. Agnes Burton, translated by R. C. Ford Detroit, MI, 1912.

Obermeyer, Brice. Delaware Tribe in a Cherokee Nation. Norman: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

Scharf, J. Thomas and Thompson Wescott. History of Philadelphia, 1609–1884. Philadelphia: L. H. Everts & Co, 1884.

Smyth, David William. A map of the province of Upper Canada, describing all the new settlements, townships, &c.: with the countries adjacent, from Quebec to Lake Huron. London: Printed by William Faden, 1813 [orig. pub. 12 April 1800]. McMaster University: Hodsoll Collection Digital Archive, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Weslager, Clinton Alfred. The Delaware Indian Westward Migration: With Texts of Two Manuscripts, 1821–22, Responding to General Lewis Cass’s Inquiries about Lenape Culture and Language. New Castle: Middle Atlantic Press, 1978.

Zeisberger, David. Diary of David Zeisberger, reprint, volume 2. Hamburg, MI: North American Books, 2006.

The name “Lenapehoking” was promoted by Lenape historian Nora Thompson Dean. See The Lenape Talking Dictionary, https://www.talk-lenape.org/detail?id=13931. For more on Lenapehoking, see Joe Baker, Hadrien Coumans, and Joel Whitney, eds., Lenapehoking: An Anthology (New York: Lenape Center & Brooklyn Public Library, 2022). ↩︎

Virtually all of the land west of the Mississippi River was considered “Indian Territory” until 1834, when that designation was restricted to the new state of Oklahoma. In 1866, the United States opened the western part of the continent to white settlers, placing both resident and relocated Native communities in direct competition for land. See “Indian Territory,” Encyclopedia Brittanica, https://www.britannica.com/place/Indian-Territory. ↩︎

See, for example, the map of Delaware and Cherokee Removal by Rebecca Dobbs in Brice Obermeyer, Delaware Tribe in a Cherokee Nation (Norman: University of Nebraska Press, 2009), 46–47. See also “Delaware,” in Bruce Trigger and William Sturtevant, eds., Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 15: Northeast (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1978), 214 and 222. ↩︎

In 1802, Lenape people still living on the reservation joined Stockbridge Indians in Oneida County, New York, and later removed to Wisconsin. Presently the area that encompassed the Brotherton Reservation is called Indian Mills. See Clinton A. Weslager, The Delaware Indian Westward Migration: With Texts of Two Manuscripts, 1821–22, Responding to General Lewis Cass’s Inquiries about Lenape Culture and Language, (New Castle: Middle Atlantic Press, 1978), 10; See also “The Brotherton Indians of New Jersey, 1780,” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, https://www.gilderlehrman.org, accessed May 20, 2024. ↩︎

Easton Treaty Texts, July 29, 1756, pt.1, quoted in James H. Merrell, “‘I Desire All That I Have Said … May Be Taken down Aright’: Revisiting Teedyuscung’s 1756 Treaty Council Speeches,” The William and Mary Quarterly 63, no. 4 (2006): 820. ↩︎

J. Thomas Scharf and Thompson Wescott, History of Philadelphia, 1609–1884 (Philadelphia: L. H. Everts & Co., 1884), 44. ↩︎

Merrell, “‘I Desire All That I Have Said,” 824. ↩︎

From “Teedyuscung’s final visit to Easton for a treaty council” in Sullivan et al., Papers of Sir William Johnson, vol. 3: 767, quoted in Merrell, “‘I Desire All That I Have Said,’” 824. ↩︎

See, for example, a November 12, 1740 letter, American Philosophical Society, Logan Papers, vol. 4: 71–72, in Robert S. Grumet, Manhattan to Minisink: American Indian Place Names of Greater New York and Vicinity (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013), 71. ↩︎

Toponym translations from Robert S. Grumet, Beyond Manhattan: A Gazetteer of Delaware Indian History Reflected in Modern-Day Place Names (Albany: New York State Museum, 2014), 80–106. ↩︎

Population estimates for Gekelmukpechunk in Weslager, Delaware Indian Westward Migration, 28, 26. ↩︎

The Delaware Prophet, Neolin, 1760, in Robert Navarre, Journal of Pontiac’s Conspiracy, ed. M. Agnes Burton, trans. R. C. Ford (Detroit, MI: 1912), 22–32. ↩︎

Grumet, Beyond Manhattan, 123. ↩︎

Coshocton is located where the Tuscarawas meets the Walhonding and becomes the Muskingum River. See Weslager, Delaware Indian Westward Migration, 28. Some have proposed an English translation of Coshocton as “river crossing” or “gathering place.” See Grumet, Beyond Manhattan, 122–23. ↩︎

Toponyms from Grumet, Beyond Manhattan, 123–126. ↩︎

The Delaware Nation at Moraviantown, “Our Story,” http://delawarenation.on.ca/about/, accessed June 5, 2022. ↩︎

Also known as the Battle of Moraviantown. ↩︎

“Our Story,” http://delawarenation.on.ca/about/. ↩︎

David Zeisberger, Diary of David Zeisberger, reprint, vol. 2 (Hamburg, MI: North American Books, 2006): 378–79. ↩︎

, by Thomas Hutchins (1730–1789), London: Printed for Robert Sayer and Thomas Jefferys, 1764. Map reproduction courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library.](/images/content/LeechM001/image1_hu3c9b902a28ab395c4d9f5b16fc8b0a5a_535169_1110x0_resize_q80_lanczos.jpeg)