Abstract

The long 19th century, which began during the last decades of the 18th century, saw many changes in the American continent. Conflicts between the different European metropolises affected the geopolitics of the Atlantic world. Throughout the geography of the American continent, widespread discontent among Creoles, Indigenous Peoples, Africans and Afrodescendants led to several rebellions, revolutions and wars. The shortage of spices and coins in North America, among many other reasons, contributed to the discontent of the subjects of the English monarchy in the Thirteen Colonies. The Napoleonic invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in 1808 added to the political collapse, weakening the power of the Spanish monarchy over its colonies.

The declaration of independence of the Thirteen Colonies in North America (1776) was followed by the revolutions of the French world in Paris, Martinique, Guadeloupe, of which the events in St. Domingue stood out, which led to the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), and the creation of the Black Republic of Haiti. The latter generated great expectations for many oppressed groups, about the possibility of repairing many of the wounds caused by the colonial projects. As such, Haiti and its proposals unleashed great fear among the enslavers, plantation owners, and colonial authorities. The Spanish American provinces began to declare their independence from 1809. The aid of the Haitian president Alexandre Pétion to Simón Bolívar, in 1815 and 1816, represented a hard blow for the Spanish forces, who tried in vain to maintain control of their colonies. By 1825, most of Spanish America, except for Cuba and Puerto Rico, had become independent.

In Brazil, Africans and Afro-descendants implemented various strategies. While many chose to flee and establish “Quilombos” or “Quilombolas”, others organized armed uprisings.1 The Malé uprising, led mainly by Muslim men, in the city of Bahia in 1835 and the Balaiada uprising, led by Maroons, in Rio de Janeiro in 1836-40, stand as some of the most impactful.2 The strategies employed by Brazilian Original Peoples were diverse, but it appears as if they evolved disconnected from the political processes of the ruling class. In fact, the process of Brazilian independence was unique and in principle with fewer armed conflicts. The Napoleonic invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in 1807 caused the Portuguese monarchs to flee Europe and take refuge in Brazil, turning this colony into the seat of the Portuguese monarchy. In 1815, the Portuguese monarchs who were still established in Brazil managed to extend and consolidate their dominions over the territories of Portugal and the Algarve, which led them to establish the United Kingdom of Brazil. This situation lasted until the Portuguese monarch’s own son, Pedro de Alcántara I, refused to return to Portugal and with the support of high-ranking officials and military officers, declared the independence of Brazil in 1822, ruling it as a constitutional monarchy until 1889, when a military coup d’état created the Republic of Brazil.

Except for the Republic of Haiti and shortly after Mexico (1823), most of the new Republics maintained slavery of Africans and Afro-descendants individuals until the mid-1850s. Although the Spanish monarchy, in principle, abolished slavery on the Iberian Peninsula in 1837, it remained in force in Puerto Rico until 1873 and in Cuba until 1886. Brazil was the last region in our hemisphere to abolish slavery in 1888. The motion of some new republics to pretend claiming Original Peoples as citizens, disavowed many of the territorial recognitions that some had achieved after much fighting and negotiations, during the colonial period.

Several metropolises managed to retain their possessions on the continent, perpetuating their colonial projects, controlling and demarcating their borders. After losing St. Domingue, its most prized colony, France revived its presence in the rest of its domains. In the case of French Guiana, it established prisons and plantations worked mostly by political prisoners, continuing the processes of dispossession of Original Peoples, Afro-descendant groups, including some French citizens perceived as undesirable. As we contemplate how colonialism expanded, we cannot ignore the fact that the United States not only appropriated Puerto Rico, but also a large part of the Mexican territory, where Original Peoples experienced additional layers of dispossession.

This section shows how republics and states, under the excuse of progress and development, once again enacted new round of dispossessions, displacing Original Peoples and Afro-descendant communities from their territories. In the North American case, the sale of the Louisiana territory that Napoleon made in 1803, to the United States initiated a new stage of dispossession of Native Peoples, causing new waves of desolation and death.

Facing with renewed versions of dispossession, excluded communities and groups continued Marroning, creating and implementing strategies of negotiation and resistance, for greater autonomy.3 From then on, that confrontation has been taken place in a much racialized and patriarchal world, more openly hostile to individuals and communities perceived as “Others.” Many free Indigenous and Afro-descendant men and women, who had no access to their land migrated to urban centers, joining groups of day laborers, forming the urban proletariat. After the abolition of slavery, many Indigenous and Afrodescendant women in urban centers ended up working as domestic workers. Many Afrodescendant women in Brazil advocated for the recognition of their labor rights. This section contains a database of domestic workers from the city of São Paolo, Brazil. Users are invited to explore and take advantage of what they offer and especially to question and note what these primary sources leave unsaid.

Lesson 13. Domestic worker activism in Brazil.

Black Women and the Labor Market: A Study of Domestic Workers in Brazil. This lesson is followed by the database: of domestic workers in the city of São Paulo, during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

[Domestic Worker’s Database Analysis](XXX Link to BLOC01)( XXX Link to BLOC02)( XXX Link to BLOC03)( XXX Link to BLOC04).

Jóvenes con Guitarra (Young Men with Guitar), Emiliano di Cavalcanti, Brazilian artist

Mulata, Haitor dos Prazeres, Brazilian artista

Lesson 14. Republicans’ Dispossessions, the Andean region, Argentina, Colombia, Venezuela.

The Frontier of the Argentine Republic to the North and East of the La Pampa Territory in 1869.

Approximate Borders of the Karanqas Aymara Polity Territoriy in the 19th century

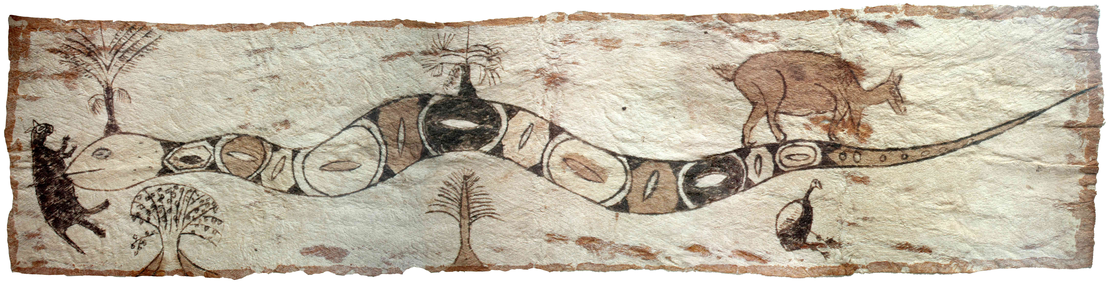

Cosmovisión Huitoto (Huitoto Cosmology), Santiago Yahuarcani, Peruvian artist.

Lesson 15. Narratives of Maroons as “Wicked,” Colonial Anthropology and Penitentiaries, Colombia and French Guiana.

Map of French Guiana Showing the Penitentiary Establishments. Paris 1874.

Doctor Crevaux’s Exploration Travels, July 9 – November 31, 1877. Paris, 1877.

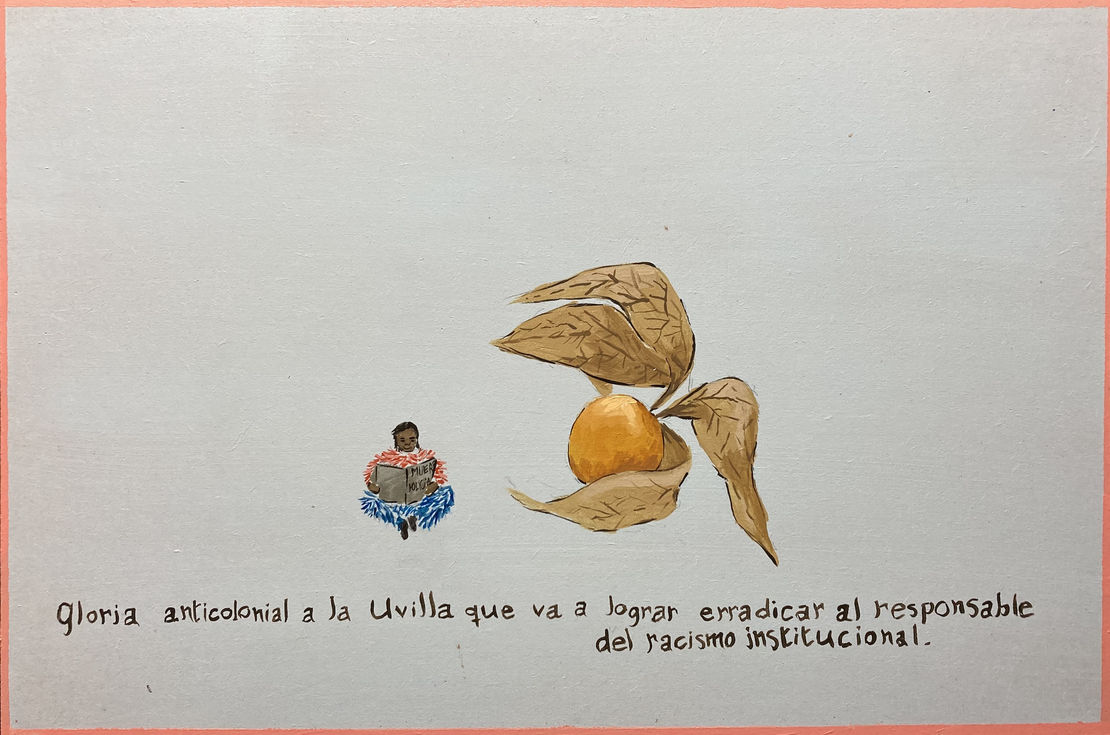

Untitled Colectivo Ruda, women artists from various Latin American countries.

Quilombos and Quilombolas are the names that Africans and Afrodescendants have used to name the communities and towns founded especially by runaways Africans, Afro-descendants, and Indigenous people in Brazil. ↩︎

Cimarrón is the term that colonial authorities used to name the enslaved person who fled in search of autonomy and freedom. ↩︎

Although the concept of “Marron” is traditionally used to refer to a slave who has ran away from the premises of their enslavers, the act of becoming a runaway includes other strategies leading to autonomy, self-sufficiency and freedom. ↩︎

, Huni Khuin, Collective of Brazilian artists.](/images/content/Laurent-PerraultE006/image1_hubd54f8e487ace5c5f35d36b8fb25266a_54569_1110x0_resize_lanczos_3.png)