Abstract

The violence and dispossession caused by colonial projects manifested themselves in different ways. One of the most violent dispossessions occurred throughout the 16th century when the clergy declared the “Indians” as perpetual neophytes or “natural children” to Christianity. This idea has since conditioned many narratives about “the Indian” as perpetually childish, ignorant, and easily manipulated, perspectives that this website seeks to dismantle.

Descriptions from early Spanish chroniclers noted with admiration how this society, even though maintained a hierarchy, there were no beggars, since everyone had their needs covered. European colonizers proclaimed legislations that reorganized, among other, the Original Peoples’ political, judicial, social, economic, cultural and spiritual structures. For example, the arrival of Governor Francisco Alvarez de Toledo to the Andean region, in 1569, brought a series of violent reforms that altered the labor structure (Mit’a), a change that affected the complex family and social web (Ayllu) that the inhabitants of the Inca state had established over several centuries. Unfortunately, throughout the American continent, colonial authorities implemented dispossession policies, justifying them within legal frameworks.

The expansion of the Transatlantic Trade of African captives and their consequent enslavement added more violence and dispossession throughout the continent. Similarly, the different colonies followed suit, creating punitive and restrictive legislation in repudiation of the strategies that Africans and Afrodescendants had been implementing in order to create spaces of autonomy, self-sufficiency and freedom. It is very important for users to understand that while the current political situation and legislations have changed significantly since the colonial period, many of the official narratives, perspectives of “otherness,” and process of dispossession and exclusion, began to take shape during the colonial period.

This section traces dispossession legislations in the Andean region and how Original Peoples opted for a variety of strategies such as alliances, negotiation, syncretism, and resistance. It notes how some individuals incorporated European-Christian elements into Andean funerary rites. It looks at how some Mayan Peoples established alliances with Spanish forces. This section recognizes how dispossession of territory forced Lenape Peoples to move, even outside of Pennsylvania. It notes how the expansion of mercury mining in Huancavélica played a fundamental role in the development of modern capitalism. It also notes how Europeans and Afro-descendants adopted customs and medicinal plants from the Original Peoples, for their relieve and recreation. This section also analyzes the horror contained in a bill of sale for an enslaved African girl in Colombia.

Lesson 7. Mayan Alliances with Spaniards in Mesoamerica. Colonial Legislation in the Andean Region.

Colonial Legislations as the Framework for Dispossessions in the Central Andes: Indigenous Tribute.

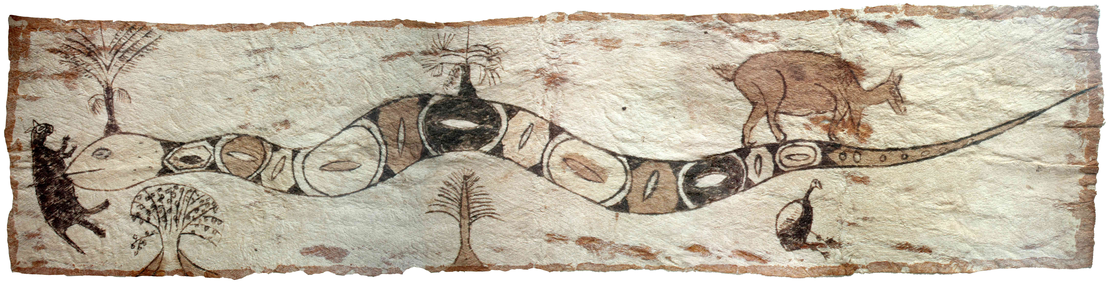

Tolteca Harry Chávez, Peruvian artist.

Lesson 8. Religious Syncretism, Understanding Lenape Diplomacy, Colonial Legislation in the Andean Region.

Afterlives of Her Animals: A Microhistory of a Burial Offering in the Colonial Andes.

Limit Demarcation of the Pueblo Real de Indios (Reduction) of Talina (1573).

Myth and Religion Series, Luis Martinez, Peruvian artist.

Lección 9. Mining, Extractivism, Colonial Labor Legislation in the Andean Region.

A Mercurial Node of Global Capitalism: How Huancavelica’s Mercury Helped to Create the Modern World.

Colonial legislations as a Framework for Dispossessions in the Central Andes: The Colonial Mita.

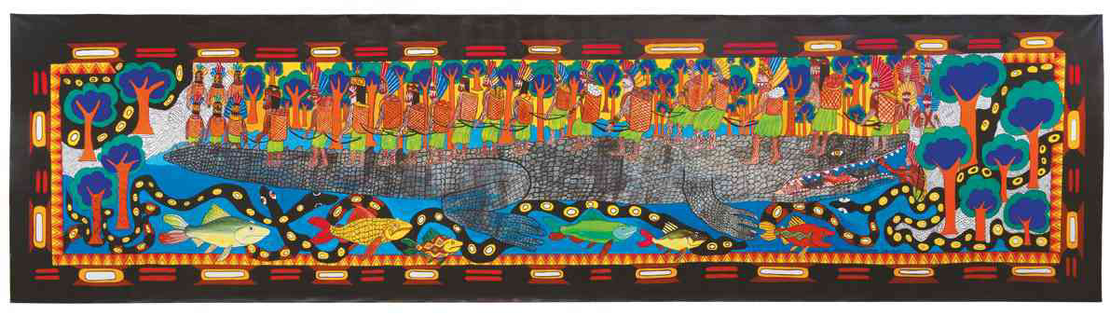

Of when the river stopped being a river to become something else, Lucho Torres Villar, Peruvian artist.

Lesson 10. Plants, Animals and their Entheogenic Derivatives; Original Peoples’ Strategies and Negotiations. Colombia, Brazil and the Andean region.

Political Ordering of the Space Under Colonial Rule at the end of the 16th Century.

What progress has left us with Ximena Alarcón, Peruvian artist.

Lesson 11. Dispossession and Negotiation of Original Peoples in the USA, the Andean Region, and Brazil

Video [Mapping Lenapehoking](/en/content/BruchacM002/)

Mapping Lenapehoking Relocations: Archival Vestiges and Histories of Place.

The Headless Mother, Adriana Ciudad Witzel, Peruvian artist.

Lesson 12. Slavery and Memory on Afro-descendant strategies.

Examining the Myth about the Enslaved Agustina: Tadó-Chocó 1795.

To further explore about archives’ silences and the roles played by enslaved women, please consult:

Hartman, S. (2008). “Venus in Two Acts”. Small Axe, 12(2), 1-14.

Laurent-Perrault, E. (2021) Cimarronaje, género y la ley, en Venezuela, 1760-1809 in Vergara Figueroa, A. y C.L. Cosme Puntiel eds. Demando mi libertad: Mujeres negras y sus estrategias de resistencia en la Nueva Granada, Venezuela y Cuba. 1700-1800. Cali: Universidad Icesi, Centro de Estudios Afrodiaspóricos. (PDF Available at: https://www.icesi.edu.co/editorial/demando-mi-libertad-2ed/)

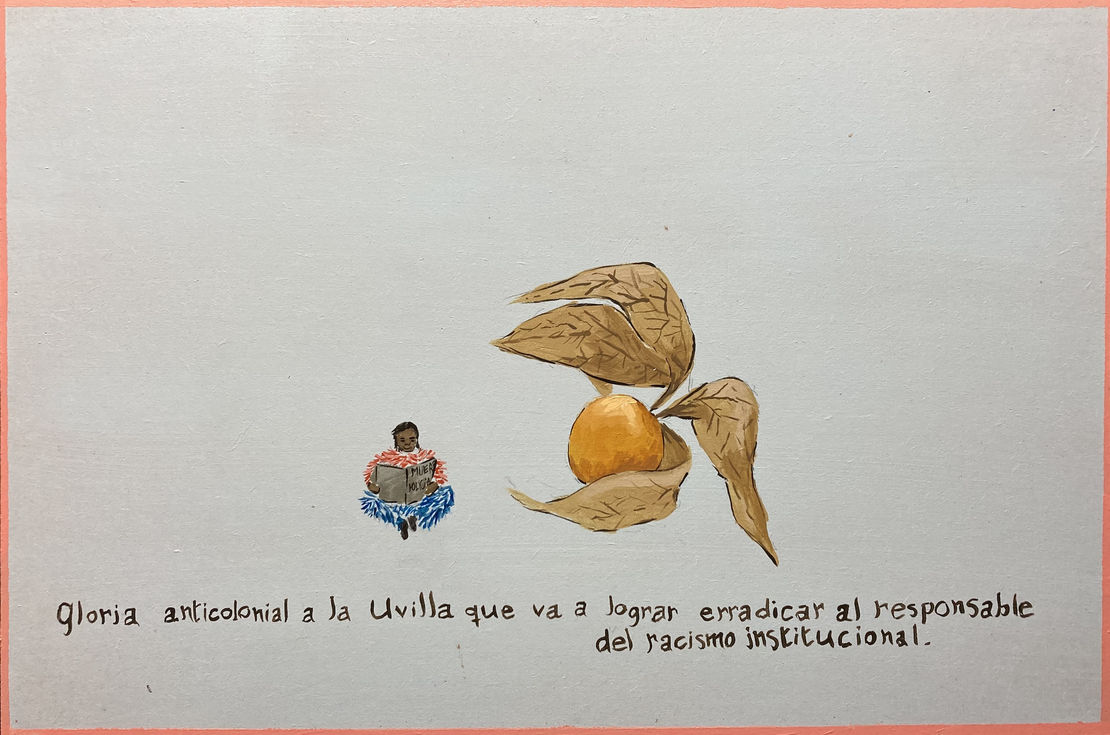

Negreros Lizette Nin, Dominican artist.

, Luis Sakiray, Peruvian artist. Enamel paint over canvas. Collection Hochschild Correa](/images/content/Laurent-PerraultE005/image1_huc5e6a5045c08f3a7959b7e48805eb938_92203_1110x0_resize_lanczos_3.png)