Abstract

The Maya from Yucatán have a long-standing written tradition that began in the pre-Hispanic era and has stood the test of time until today. This tradition is displayed in the numerous documents they wrote on stone, pottery, and paper, where they recorded their history, their thinking and worldview. During pre-Hispanic times, they documented their writing using hieroglyphs. From the 16th century onwards, they resorted to the Latin alphabet to continue recording their history and culture. Today, these documents are mainly kept in museums, libraries and archives in Mexico and the United States of America, for scholarly research. Contrary to this, they are inaccessible to Yucatec Maya today despite them being their documentary heritage. This fact is a plain denial of their rights to their documentary heritage and a sign of the dispossession and intellectual stripping and extraction that they have experienced for two centuries. Some of the actions we propose to secure the rights of the Yucatec Maya to their documentary heritage today are to distribute books on this subject in schools and to restitute and return copies of historical documents to the Maya communities.

The Written Tradition of the Yucatec Maya and their Documentary Heritage

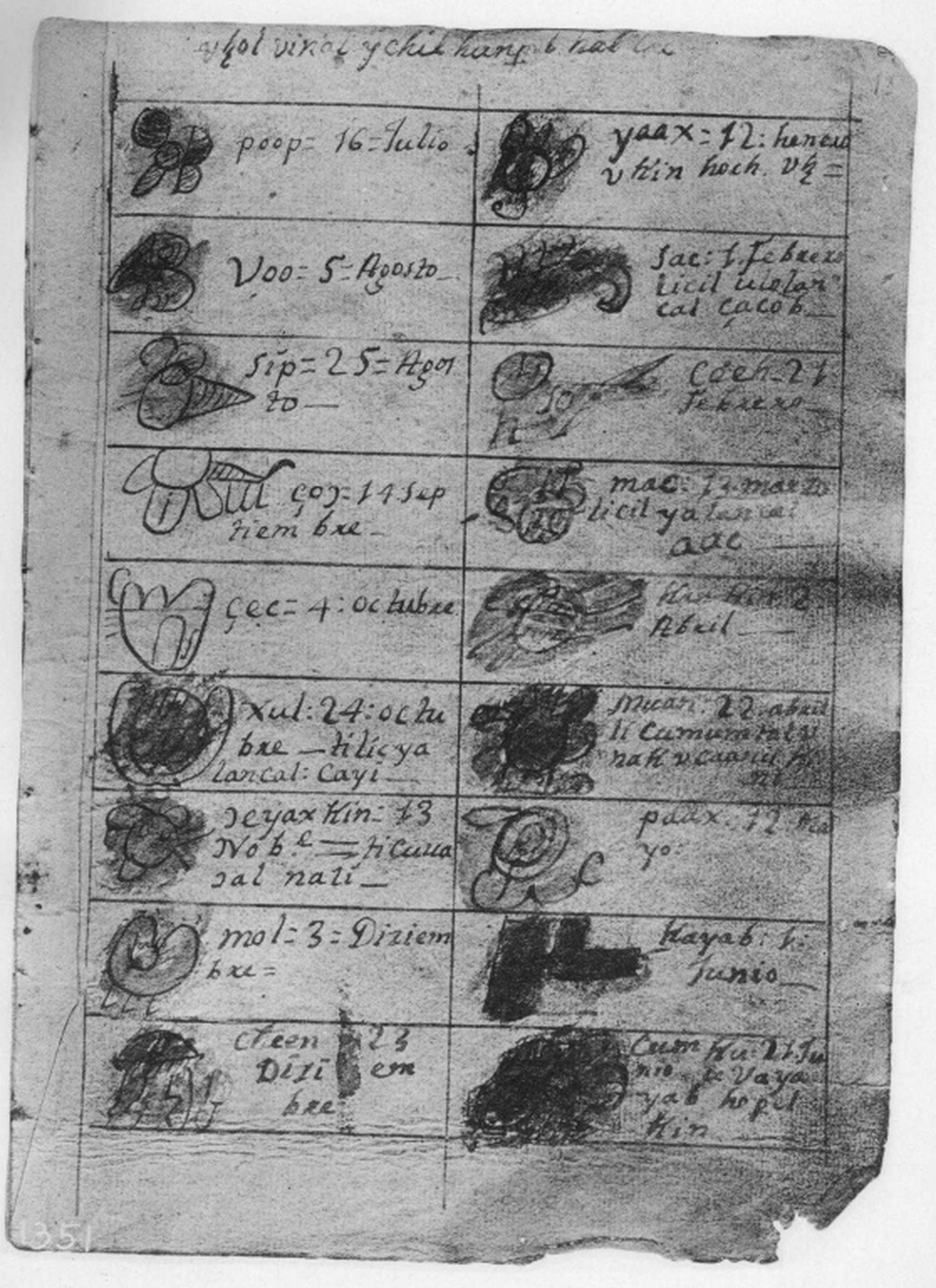

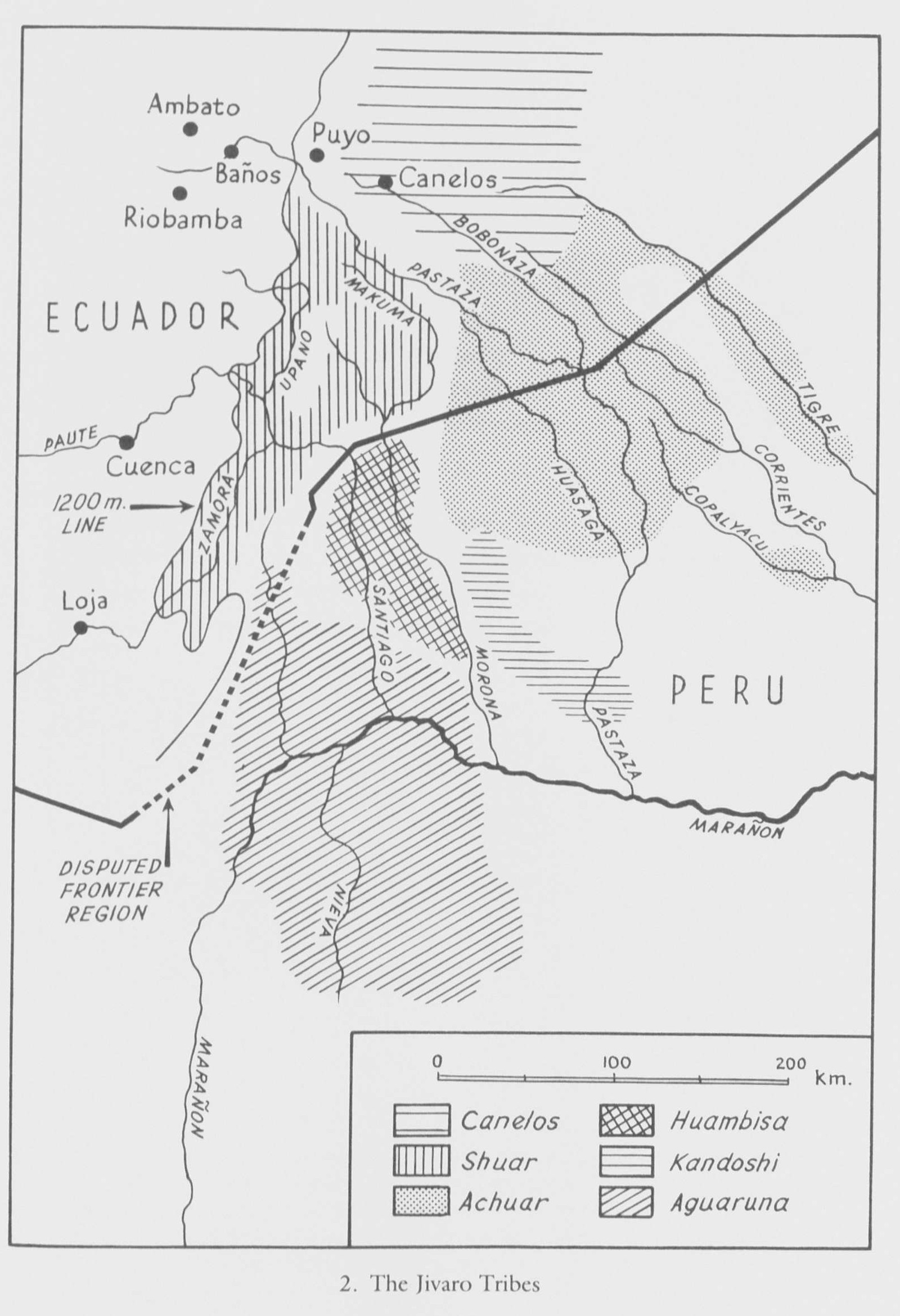

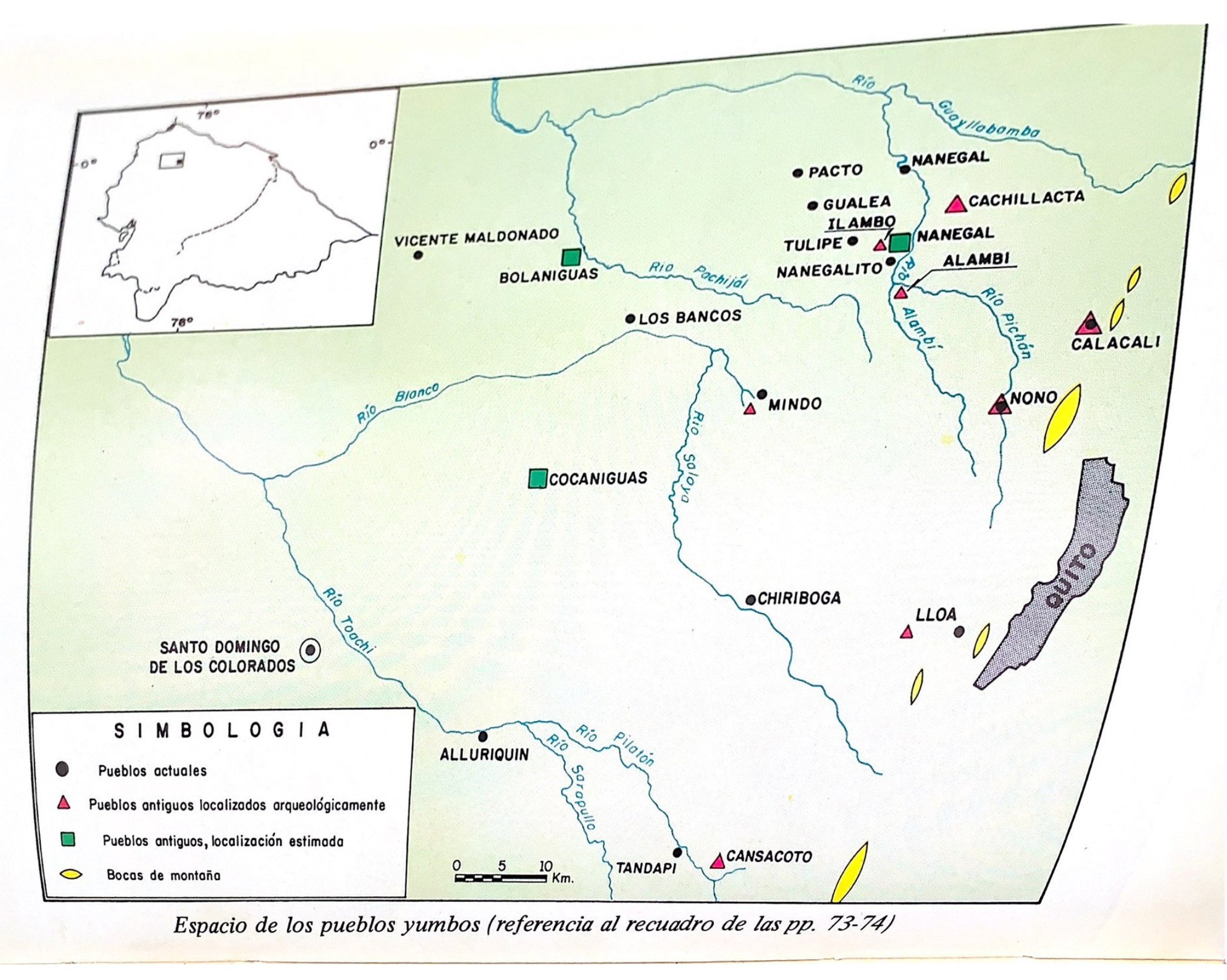

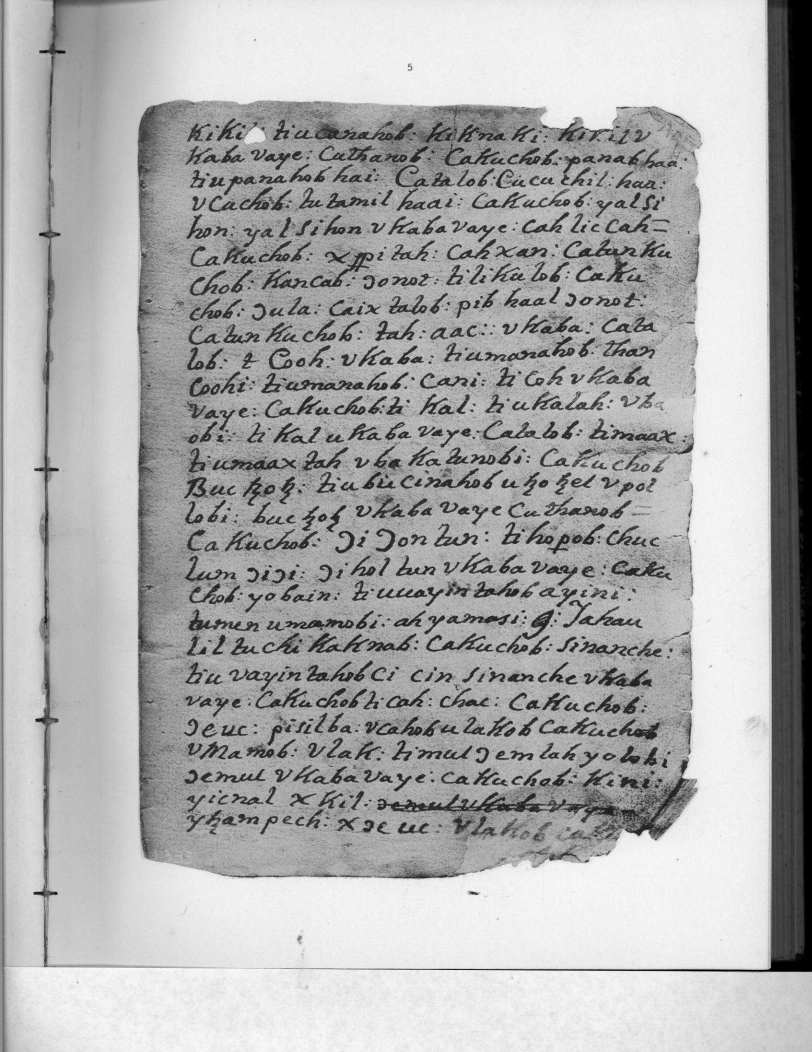

The pre-Hispanic Maya peoples of the Yucatan Peninsula developed a complex hieroglyphic writing system that marked the beginning of an extensive written tradition that is still preserved among their descendants. During the Classic (150 BC. -900 AD.) and Post-Classic Periods (900-1521 AD.), they used hieroglyphic system on stone, paper, leather, and pottery to record historical, astronomical, calendrical, and religious events.1 This written tradition was not interrupted by the conquest and colonization that ensued in the Yucatan peninsula in the mid-16th century. The Yucatec Maya used the Latin alphabet to continue writing —both on paper and in their first language— about the political and religious events they experienced during the colonial period, in addition to divinatory texts, wills, land titles, medicinal prescriptions, prayer books and literature (see image 1). Due to the historical context of their production, these documents show a certain degree of influence of Western philosophy in both their content and structure.2

At present, Maya writers have produced abundant publications on topics of oral tradition, dictionaries, grammar books, Mayan language courses for elementary schools, and literary works.3 In this sense, the corpus of documents written by the Yucatec Maya from pre-Hispanic times to the present has become part of their documentary heritage. Indeed, it may be defined as the artistic, historical, cultural, folkloric, educational, intellectual, and scientific expressions of a society. It also casts light on the development of the peoples who created it. Additionally, their legacy stores, transmits, preserves, communicates, and disseminates knowledge both to the society that produced it and to subsequent generations. It stands as a substantial part of humanity´s cultural heritage.4 The written production of the past and present Yucatec Maya peoples can certainly be catalogued as documentary heritage.

Image 1. Page 5 of the book of Chilám Balam de Chumayel (1782)

Source: The Museum Anthropological Publications, 1913.

Maya Documentary Heritage: Unknown and Inaccessible to the Yucatec Maya Themselves

The documentary heritage of the Maya peoples from Yucatán presents two contrasting features or opposites. On the one hand, its wide use and dissemination among scholars is highlighted as a source to rebuild part of the history of Yucatec Maya, as well as to learn about their past and present cultural practices. On the other hand, this heritage is practically unknown and inaccessible to the Yucatec Maya themselves. This is attributed to the fact that the Mayan documents that are still preserved, are kept in libraries and archives located in cities both in Mexico and abroad, which can hardly be frequented by the Maya peoples. This has led to a grievous disconnect between these Indigenous peoples and their documentary heritage as a source of history and identity. It additionally uncovers the academic dispossession and extractivism the Maya of Yucatán have experienced vis-à-vis their documentary heritage, as well as the blatant denial of their rights to know, access, value and safeguard their documentary heritage.

The Documentary Heritage of the Yucatec Maya and the National and International Normative Frameworks.

The dissociation and disconnect of the Yucatec Maya and their documentary heritage is more noticeable today, as a number of national and international normative frameworks currently protect the rights of Mexico’s Indigenous peoples over their historical, cultural, and natural heritage. More specifically, the two international normative frameworks that protect the rights of Indigenous peoples over their heritage are Convention 169 concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries (1989) of the International Labor Organization (ILO) and the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. ILO´s Convention 169 was adopted by Mexico in July 1990 and is binding in matters relating to Indigenous peoples. Article 2 makes governments accountable for protecting the social, economic, and cultural rights of Indigenous peoples and for securing respect for their integrity. Additionally, Article 27 urges that education programs and services consider Indigenous peoples´ own history. So far, neither of these two articles has had any effect on the Yucatec Maya´s reality and documentary heritage.

In turn, the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples expresses more distinctly the rights that Indigenous peoples have over their heritage. Article 11 declares that indigenous peoples have “the right to maintain, protect and develop the past, present and future expressions of their cultures”, and announces that States should grant them redress, which may include restitution for cultural, intellectual, religious and spiritual property of which they may have been deprived without their consent. In addition to this, Article 13 asserts the right of Indigenous peoples “to revitalize, use, promote and transmit to future generations their experiences, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures, and to appoint, name and maintain their communities, places, and persons. As in the case of ILO´s Convention 169, these three articles have proven to be a hopeless cul-de-sac to enforce the rights of the Yucatec Maya over their documentary heritage.

One of the regulatory frameworks on Indigenous matters in Mexico is the Federal Act for the Protection of Cultural Heritage of Indigenous and Afro-Mexican Peoples and Communities (LFPPCPCIA as per acronym in Spanish), issued by the Mexican government in January 2022. According to Article 2, one of the main purposes of this act is to “acknowledge and guarantee the peoples´ property rights that make up their cultural heritage, their traditional knowledge and cultural expressions, as well as the collective intellectual property with respect to such heritage.” It also sets forth the implementation of measures for Indigenous and Afro-Mexican peoples and communities to preserve, protect, control, and develop the elements that make up their cultural heritage, knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions.

Article 13 of this act establishes that the Mexican State´s mission is to acknowledge “the collective right that the indigenous and Afro-Mexican peoples and communities bear to own their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and cultural expressions, as well as the related expressions that… they have practiced and have been transmitted to them by members of their own community from earlier generations. They also have the right to the intellectual property of such heritage.” In effect, provisions in Articles 2 and 13 have had no positive effects for the Maya peoples of Yucatan. The Mexican State has neither recognized the right that these peoples have over documentary heritage, nor their right to intellectual property over this same heritage.

Proposals for Linking and Connecting the Yucatec Maya with their Documentary Heritage

We have depicted an unfavorable scenario that reflects the current estrangement between the Yucatec Maya and their documentary heritage, as well as the ineffective outcomes of some articles to enforce the rights of the Maya peoples over this legacy. Faced with such a situation, we seek proposals to put forward in an attempt to transform the experiences of the Yucatec Maya and their rights over their documentary heritage. The following are some ways for present-day Yucatec Maya to approach their documentary heritage as an essential part of their history and identity.

Publication of an awareness-raising and dissemination catalog containing historical and contemporary documents produced by the Maya peoples from pre-Hispanic times to the present.

Distribution of the catalog in the schools of villages where the Mayan documents were produced.

Restitution of copies or facsimiles of historical documents to the people to whom they belong.

Temporary exhibitions of Maya documentary heritage in the towns where the historical and contemporary texts were produced.

Development of talks or lectures on topics related to Maya documentary heritage, mainly in the towns where the documents originated.

Creation of a documentation center for the Yucatec Maya peoples´ documentary heritage in the Maya villages with emblematic historical, symbolic, and cultural features.

Dissemination among the Maya peoples of Yucatan of the international and national legal frameworks that protect the rights of Indigenous peoples over their historical, cultural, and natural heritage.

Final Remarks

Thanks to the development of a complex writing system, the pre-Hispanic Maya peoples were able to draft documents recording their philosophy and history. In this way, they laid the foundations of a rich written tradition that has stood the test of time to the present day. Neither the conquest and colonization, nor the political, social, economic, and educational transformations since the 19th century to-date could halt the calling of the Mayan scribes. At present, Yucatec Maya intellectuals, writers and academics perpetuate the written tradition of their ancestors through the publication of various texts in their own language. All these historical documents that originated in pre-Hispanic times and have withstood time, constitute the documentary heritage of the Yucatec Maya today. Regrettably, this heritage is unknown and inaccessible to the Maya themselves. This reflects the dispossession and extractivism of their documentary heritage. It also shows the denial of their rights due to the Mexican State´s lack of interest in applying the laws to acknowledge and secure the property rights of Indigenous peoples. In response to this problem, we have proposed seven routes to connect and link the Maya to their documentary heritage as sources of their history and identity.

Bibliography

Brody, Michal (2007). “Un panorama del estatus actual del maya yucateco escrito,” in Desacatos, num. 23, January-April, México, CIESAS, pp. 275-288.

De Coe, Michael (2001). El desciframiento de los glifos mayas, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Fahsen Ortega, Federico y Daniel Matul Morales (2007). Los códices mayas. Los códices de Dresde, Paris y Grolier. Ri Mayatzib k’o Dresde, Paris xuquje’ri Xk’ut pa Grolier, Guatemala, Liga Maya Guatemala/The Royal Norwegian Embassy in Guatemala.

Lacadena García-Gallo, Alfonso (2015). “Lengua y literatura mayas jeroglíficas,” in Cortina Martínez de Velasco and María Elena Vega Villalobos (eds.), los mayas: voces de piedra, 2ª ed. Madrid, Turner/ Ámbar Diseño Publishers/UNAM, 2015, pp. 113-121.

Palma Peña, Juan Miguel (2013). “El patrimonio cultural, bibliográfico y documental de la humanidad. Revisiones conceptuales, legislativas e informatvas para una educación sobre patrimonio,” in Cuicuilco, vol. 20, num. 58, September-December, México, ENAH. pp. 31-57.

Proskouriakoff, Tatiana (1999). Historia maya, México, Siglo XXI Editores Publishing Company.

Schele, Linda y Peter Mathews (1998). The Code of Kings. The Lenguage of Seven Sacred Maya Temples and Tombs, New York, Scribner.

The Museum Anthropological Publications (1913). The Book of Chilám Balam of Chumayel, vol. V, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, University Museum.

Vail, Gabrielle (2009). “Cosmology and Creation in Late Postclassic Maya Literature and Art,” in Leslie G. Cecil and Timothy W. Pugh (eds), Maya Worldviews at Conquest, University Press of Colorado, Boulder, pp. 83 -110.

Some of the research that addresses these issues can be found in Schele and Mathews, 1998; Proskouriakoff 1999, De Coe, 2001; Fahsen and Matul, 2007; Vail, 2009; Lacadena, 20015. ↩︎

More specifically, we may refer to some of the following historical documents: the Chilám Balam of Chumayel, Tizimin, Kaua, Ixil, Nah, Tekax, Chan Kah and the Pérez Codex, written between the 16th and 19th centuries. Other important colonial texts are the Titles of Ebtún (between 1650 and 1820), the testaments of Cacalchen (ca. 1650) and Ixil (ca. 1750). There is also a vast number of texts in Maya that gave way to the Indian republics during the colonial period. ↩︎

In this paper Brody (2015) presents an overview of the current writing of the Yucatec Maya and shows the abundant publications in Mayan language and the social conditions that drove the development of this indigenous language. He analyzes books, pamphlets, periodicals, magazines and official documents, many of which consist of pedagogical materials and tools for literacy and the teaching of Yucatec Mayan. ↩︎

Palma, 2013: 41-43. ↩︎