Abstract

In the past few years, the Indigenous movement has emerged as one of the strongest social movements in Brazil, embedded in a long history of resistance to settler-colonialism and genocide. The land struggle carried out by the Tupinambá of Serra do Padeiro, in Southern Bahia, in the Northeast of the country, provide a striking example of Indigenous mobilization to assert territorial rights. In 2004, they began to carry out direct actions, called retomadas de terras, to recover their territory, which, from the end of the 19th century onwards, had been turned by non-Indigenous settlers into cocoa farms and resorts.1 By doing so, they have been able to revert the diaspora triggered by the loss of their lands. Despite being heavily targeted by criminalization, paramilitary attacks, and police brutality, after 95 retomadas, they regained possession of around two thirds of the territory, even though the official demarcation of their land, which also began in 2004, is not over yet.2 Through their mobilization, the Tupinambá have forged a thriving collective project aimed at creating conditions for viver bem (living well), which forms part of broader ongoing decolonization processes. This research was supported by the National Association for Indigenous Affairs (ANAÍ).

The Tupinambá of Serra do Padeiro, who live in one of the few remaining patches of Atlantic Forest, in Southern Bahia, in the Northeast of Brazil, provide a striking example of the vitality of the political mobilization of Indigenous peoples in the country. Stretching for around 47,000 hectares, the Tupinambá de Olivença Indigenous Territory comprises more than 20 villages, including Serra do Padeiro, which is located in a hilly region on the western border.3 Recent estimates indicate that the population of the Indigenous territory revolves around 5,000 people, not counting the non-Indigenous settlers still living in the area.4

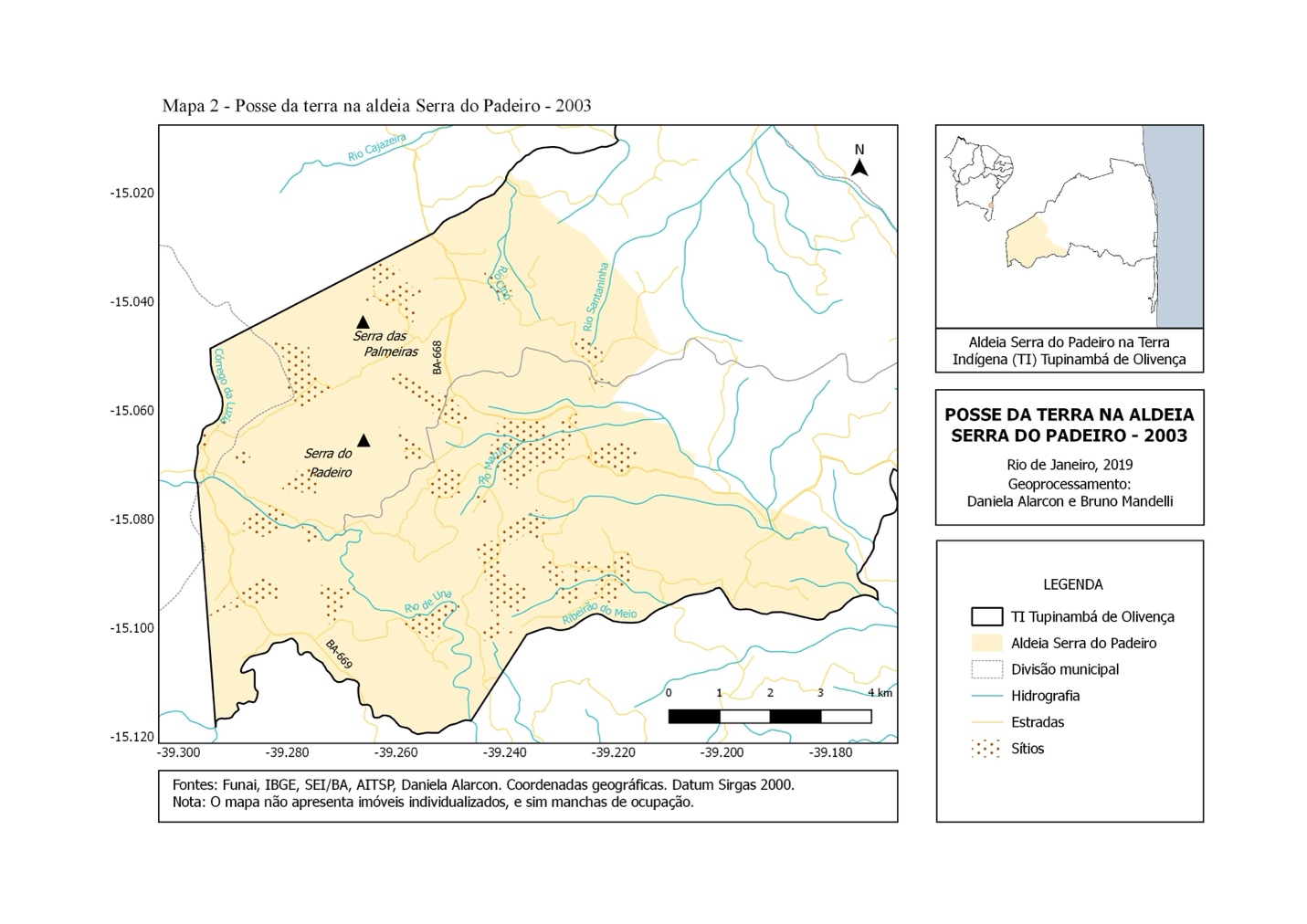

Land tenure in Serra do Padeiro in 2003. Due to dispossession, the Tupinambá of Serra do Padeiro were restricted to less than 10% of their territory (dotted areas). Source: Alarcon (2022, p. 119).

Rooted in their territory, engaged in the broader Indigenous movement, and connected to both their ancestors and non-human beings (including the encantados, the main cosmological entities in Serra do Padeiro), the Tupinambá have forged a thriving collective project aimed at creating conditions for viver bem (living well). In the last decades, specific and contextual notions of living well, such as those formulated by the Tupinambá and the Guarani and Kaiowa, from the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, in central-western Brazil began to circulate more widely 5. Crossing state borders and ethnicities, they have engendered a particular mobilizing idiom, shared by Indigenous peoples and other groups involved in territorial struggles. Especially well-known are the expressions buen vivir or vivir bien, Spanish translations for concepts formulated by Indigenous peoples in Bolivia and Ecuador, such as sumaj qamaña (Aymara) and sumak kawsay (Quechua)6. According to Pacheco de Oliveira (2018), these notions, as well as the retomadas – which can be roughly translated as land retakings –, should be understood as part of decolonization processes7. It is possible to establish parallels between them and the broad constellation of actions which, in other contexts, fall under the expression land back.

Referring to the territorial recovery process, the Tupinambá of Serra do Padeiro often use the category return of the land. As we can see, it is the land that returns, as the Indigenous mobilization liberates portions of the territory that had been trapped in cocoa farms. Some members of the community explicitly say that they have been setting the land free. It is crucial to acknowledge that the land is the main character here. According to their cosmology, the Tupinambá do not own the land, but have the duty to tender to it, as determined by the encantados. Affected by dispossession, these entities want the land back. Communicating with the Tupinambá through different channels, including physical incorporations, they have pushed them to engage in direct action.

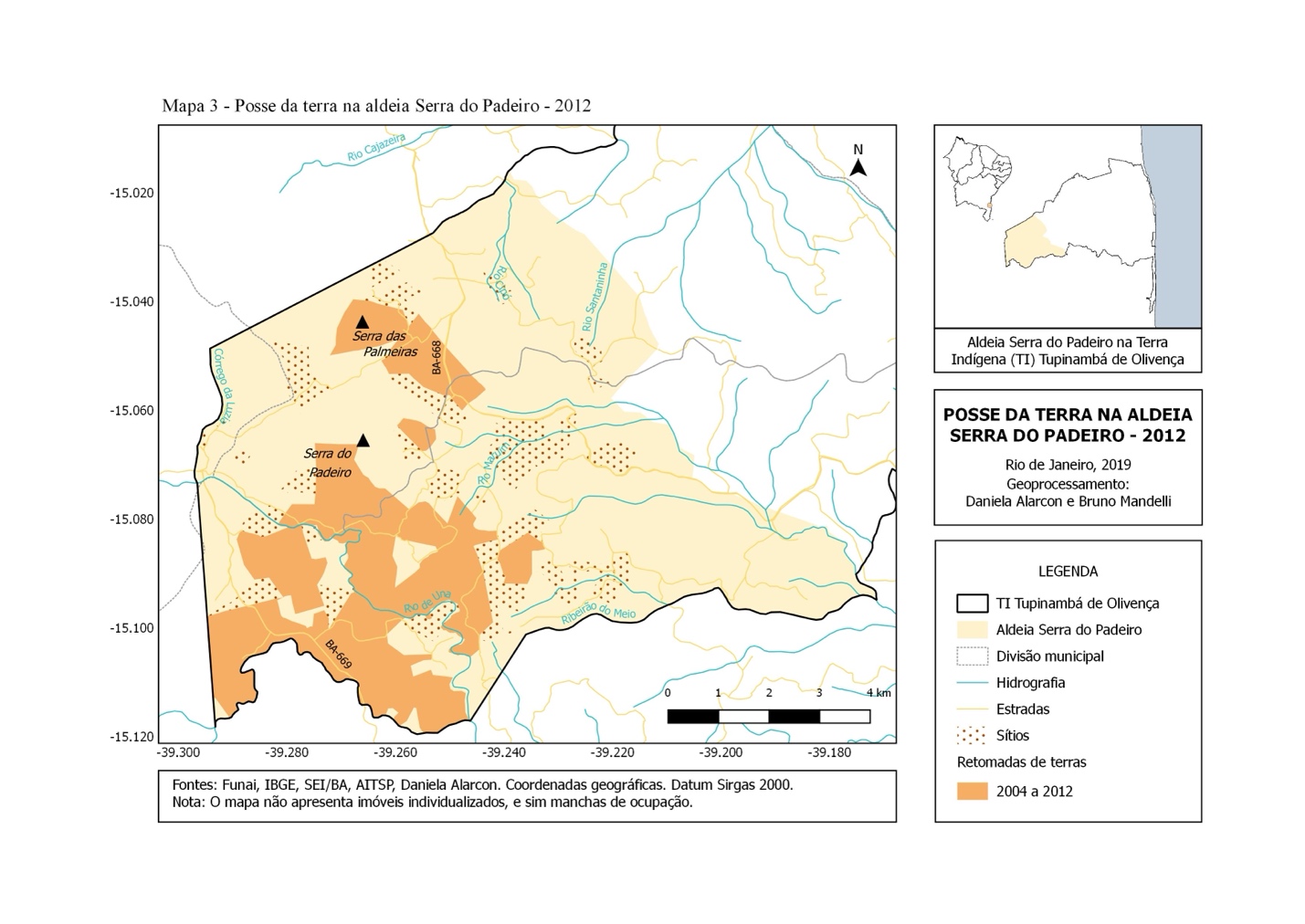

Land tenure in Serra do Padeiro in 2012. After a first round of direct actions (retomadas de terras), the Tupinambá began to recover important portions of their territory (orange areas). Source: Alarcon (2022, p. 120).

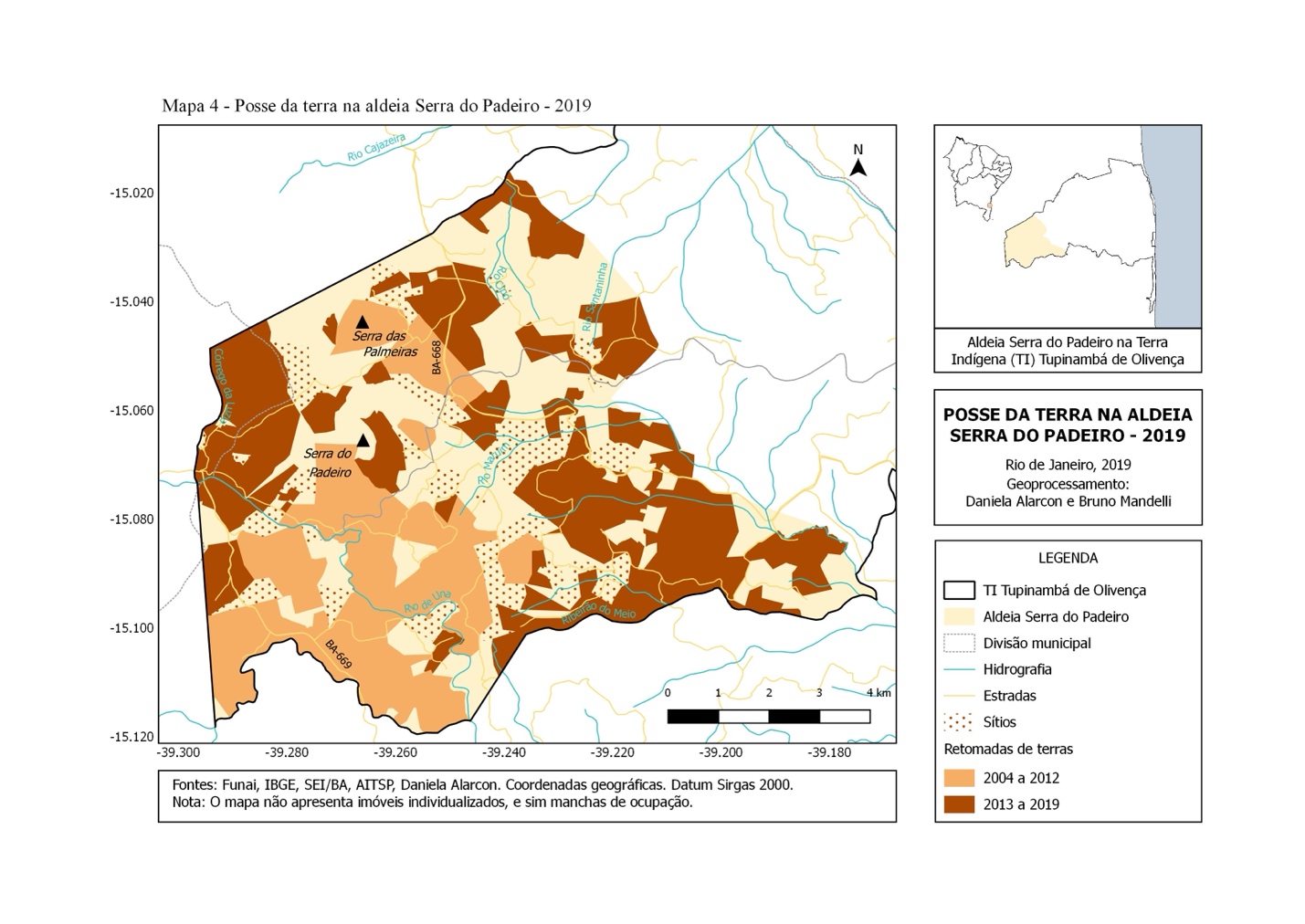

The territorial recovery has dramatically changed land tenure in Serra do Padeiro. The village covers approximately 8,500 hectares, including inhabited areas, gardens, and forests. Before the first retomadas, the Tupinambá of Serra do Padeiro were in possession of about 10% of the area. Despite the appropriation of their lands by non-Indigenous settlers and the diaspora, through decades, some families have been able to maintain smallholdings. In my investigations, I mapped around 40 smallholdings in Serra do Padeiro, most of which comprised of 20 hectares or less. Careless observers might interpret the maintenance of the smallholding as defeat or at least as a minor win, considering that the Tupinambá once possessed the entire territory. I argue, in contrast, that these “insignificant” victories would form a crucial basis for the contemporary political action. It is because many relatives stayed in the land, even if confined, that the Tupinambá claim that they never left it as a people, even if many individuals and families experienced the diaspora. Staying in the land was crucial to the territorial struggle, both in tactical and strategical terms.

The return of the land unfolds in circumscribed but connected returns, such as the return of the encantados and the return of relatives. Mobilizing relatives to engage in the struggle and creating everyday forms of living together, the Tupinambá have been defining a collective project for village construction, in which land is not viewed as a tradable property, but as a precondition for living well. In 2016, I carried out a census in the village, counting 483 people, 321 living in retomadas and 162 in smallholdings. The fact that, when the census was carried out, approximately two thirds of the Indigenous population of Serra do Padeiro lived in retomadas gives us a sense of their relevance. To fully comprehend their central role in the life of the Tupinambá, it should be added that many families living in smallholdings practice most of their economic activities – small scale farming, raising of small animals, fishing, gathering, and hunting – in retomadas. In those areas, while still tending the existing cocoa trees, to sell their beans and produce chocolate, the Tupinambá have also reintroduced native species, complexifying the landscape.

The census also revealed that approximately 60% of the individuals living in Serra do Padeiro in 2016 had experienced the diaspora – meaning that more than half of the village’s population had, at some point, engaged in an itinerary of return. About three quarters of the total population had been born before the beginning of the recovery process. In that universe, 70% lived in the diaspora. On the other hand, if we isolate the group of individuals who were born after 2004, the tendency is reverted, with only approximately 25% having lived outside the village. As we can see, the diaspora is less present among the younger population. That does not mean that people do not leave the territory anymore. They do, under various circumstances, which vary from the curiosity of the youngsters for urban life, the pursuit for higher education, the necessity of medical treatments which are still not offered in the village, or even family conflicts. The difference now is that people have a land basis, are fostering a thriving economy, and have access to rights, such as primary and secondary education, and basic healthcare, all derived from the mobilization to recover territory. Even though the demarcation of the Tupinambá de Olivença Indigenous Territory is not over yet – which renders the land tenure precarious –, the socioeconomical transformations are so profound that, in a way, it is even hard to measure them.

To a greater or lesser extent, returning relatives can be found in practically all of the extended families in the village. In some families, the data on returns is striking; let us focus on one extended family as an example. Three generations were heavily impacted by dispossession, with their members wandering between farms and cities, and working even in situations analogous to slavery. In 2004, before the onset of the territorial recovery, 15 individuals of this family lived in the village, clustered around one relative who maintained a smallholding. In 2019, 72 extended family members lived spread over five retomadas and one smallholding. In the past few years, even some nuclear families who had apparently consolidated their permanence in the city returned, strongly undermining the assertion of “trajectories of no return”8.

Land tenure in Serra do Padeiro in 2019. From 2013, the territorial recovery process intensified and the Indigenous community regained access to new portions of land (brown areas). Now, they are in possession of approximately 70% of their territory. Source: Alarcon (2022, p. 121).

In response to the Tupinambá mobilization, various actors, mainly from local and regional elites, have engendered a set of strategies seeking to halt the demarcation process and revert the territorial recovery, frequently resorting to open violence. Farmers and other subjects have hired gunmen and established paramilitary groups, which carried out ambushes, beatings, targeted killings, and other attacks. They have also engaged in other forms of action, for instance filing a myriad of possessory actions9 and other lawsuits or putting pressure to the Executive branch, through private meetings with ministers and other high-rank officers. In 2013, an anti-demarcation association took legal action attempting to cancel the official recognition of the Indigenous territory.10 In 2016, the Superior Court of Justice (STF) would unanimously decide that the demarcation process should move forward11. It should be mentioned, however, that a previous injunction by one of the judges had frozen the demarcation process for almost six months12.

Another aspect of the judicialization of the case is the criminalization of Indigenous leaders. Numerous individuals from Serra do Padeiro and other villages have been indicted – for trespassing with the intent to steal, criminal association, and other charges – and arrested. Two of the most emblematic cases involved Tupinambá from Serra do Padeiro: Cacique Babau (Rosivaldo Ferreira da Silva), who was arrested four times, and even sent to a maximum-security prison; and Glicéria Tupinambá (Glicéria Jesus da Silva), who was arrested in 2010 with her 2-month-old baby, an incarceration which lasted for two months and was severely criticized by human rights organizations. Law specialists have emphasized that the imprisonments were illegal13. In 2010, both Cacique Babau and Glicéria were put under protective measures established for threatened human rights defenders, due to recurring threats. Because of the rapid advancement of the territorial recovery, the Tupinambá became widely known – to some, as a paradigm of a dangerous social process that should be dismantled by all means. Negative views on the retaking process are put forth not only by those directed impacted by them, but also by wider conservative sectors, part of traditional or emergent economical elites. On the other hand, this form of action has been acclaimed by the Indigenous movement and progressive actors in general as legitimate and effective means of reverting expropriation, dating back as least to the end of the 1970s, and engaged in by Indigenous peoples from all over the country.

Closing this brief overview, it is important to emphasize that the territorial recovery is a dynamic process, within which the strategies of mobilization are transformed daily, informed by both deeper and circumstantial reasons. The creativity and innovation of the Indigenous movement are built over a repertoire of collective action crafted through centuries and connected to the struggles of quilombolas, peasants, and other social subjects, in a country where a thorough land reform has never occurred 14. In different settings, Indigenous peoples have developed intricate, and often successful, strategies to fight for their livelihoods, with special emphasis on their territorial rights, understood as foundational ones. Challenging celebratory interpretations of the state policies for Indigenous peoples in Republican Brazil – particularly, romanticized views on the Indian Protection Service (SPI), founded in 1910 and replaced by the National Indian Foundation (Funai) in 196715 –, there is a growing perception of the key role played by Indigenous peoples, frequently through direct action, in asserting their territorial rights.

References

Acosta, Alberto. 2013. El Buen Vivir: Sumak Kawsay, Una Oportunidad Para Imaginar Otro Mundo. Vilassar de Dalt: Icaria Editorial.

Alarcon, Daniela F. “Doze Anos de Luta pela Demarcação da TI Tupinambá de Olivença.” In Povos Indígenas no Brasil: 2011–2016, edited by Beto Ricardo, and Fany Ricardo, 713–717. São Paulo: Instituto Socioambiental, 2017.

Alarcon, Daniela F. 2019. O Retorno da Terra: As Retomadas na Aldeia Tupinambá da Serra do Padeiro, Sul da Bahia. São Paulo: Editora Elefante.

Alarcon, Daniela F. 2022. O Retorno dos Parentes: Mobilização e Recuperação Territorial entre os Tupinambá da Serra do Padeiro, Sul da Bahia. Rio de Janeiro: E-Papers/LACED.

Almeida, Alfredo W. B. 2008. Terras de Quilombos, Terras Indígenas, “Babaçuais Livres,” “Castanhais do Povo,” Faxinais e Fundos de Pastos: Terras Tradicionalmente Ocupadas. Manaus: PGSCA–UFAM.

Bezerra, André A. S. “Consenso e Força Perante a Mobilização Tupinambá: O Discurso do Poder dos Meios de Comunicação e do Judiciário.” Ph.D diss., Universidade de São Paulo, 2017.

Brasil. Comissão Nacional da Verdade. “Violações de Direitos Humanos dos Povos Indígenas.” In Relatório, vol. II – Textos Temáticos, 204–262. Brasília: CNV, 2014.

Brasil. Procuradoria-Geral da República. “STJ Mantém Processo de Demarcação da Terra Indígena Tupinambá, na Bahia.” MPF – Notícias. September 15, 2016. http://www.mpf.mp.br/pgr/noticias-pgr/stj-mantem-processo-de-demarcacao-da-terra-indi gena-tupinamba-na-bahia.

Comerford, John C.1999. Fazendo a Luta: Sociabilidade, Falas e Rituais na Construção de Organizações Camponesas. Rio de Janeiro: Relume Dumará/Núcleo de Antropologia da Política, UFRJ.

Mura, Fabio. “À Procura do ‘Bom Viver:’ Território, Tradição de Conhecimento e Ecologia Doméstica entre os Kaiowa.” Ph.D diss., Museu Nacional da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 2006.

Pacheco de Oliveira, João. 2018. “Fighting for Lands and Reframing the Culture.” Vibrant – Virtual Brazilian Anthropology 15(2): 1–21.

Schavelzon, Salvador. 2015. Plurinacionalidad y Vivir Bien/Buen Vivir: Dos Conceptos Leídos Desde Bolivia y Ecuador Post-constituyentes. Quito: Abya Yala.

Sigaud, Lygia. 2005. “As Condições de Possibilidade das Ocupações de Terra.” Tempo Social 17(1): 255–280.

Souza Lima, Antonio C. 1995. Um Grande Cerco de Paz: Poder Tutelar, Indianidade e Formação do Estado no Brasil. Petrópolis: Vozes.

Vega, Ailén et al. 2022. “Those Who Live Like Us: Autodemarcations and the Co-becoming of Indigenous and Beiradeiros on the Upper Tapajós River, Brazilian Amazonia.” Geoforum 129: 39–48.

For a detailed literature review and a more comprehensive debate on the implications of the cocoa plantations among the Tupinambá, see Daniela F. Alarcon, *O Retorno da Terra: As Retomadas na Aldeia Tupinambá da Serra do Padeiro, Sul da Bahia *(São Paulo: Editora Elefante, 2019) and Daniela F. Alarcon, O Retorno dos Parentes: Mobilização e Recuperação Territorial entre os Tupinambá da Serra do Padeiro, Sul da Bahia (Rio de Janeiro: E-Papers/Laced, 2022). ↩︎

The systematic violation of the deadlines determined for the procedure led the Public Attorney’s Office to file a series of civil actions against the state. ↩︎

The Indigenous territory stretches for portions of the cities of Buerarema, Ilhéus, São José da Vitória, and Una. ↩︎

According to the Special Secretariat for Indigenous Health, Ministry of Health, the Indigenous population of the Tupinambá de Olivença Indigenous Territory in 2019 was 5,038 people. ↩︎

On the Guarani and Kaiowa, see Fabio Mura, “À Procura do ‘Bom Viver:’ Território, Tradição de Conhecimento e Ecologia Doméstica entre os Kaiowa” (Ph.D diss., Museu Nacional da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 2006). ↩︎

See Salvador Schavelzon, Plurinacionalidad y Vivir Bien/Buen Vivir: Dos Conceptos Leídos Desde Bolivia y Ecuador Post-constituyentes (Quito: Abya Yala, 2015) and Alberto Acosta, El Buen Vivir: Sumak Kawsay, Una Oportunidad Para Imaginar Otro Mundo (Vilassar de Dalt: Icaria Editorial, 2013). ↩︎

João Pacheco de Oliveira, “Fighting for Lands and Reframing the Culture,” Vibrant – Virtual Brazilian Anthropology 15, no. 2 (2018): 1–21. ↩︎

For a long time, dominant views on urbanization and migration within social science have assumed that, once individuals and groups leave rural areas, there is no return. In other words, the “transformation” of peasants in urban workers or the “de-indigenization” of contacted Indigenous peoples would be “natural” and irreversible processes. However, careful analysis of the Tupinambá case and various other contexts reveal the flaws of these perspectives. ↩︎

Possessory actions comprise different types of legal processes through which land title holders seek to prevent (interditos proibitórios) or revert (reintegrações de posse) land “invasions.” ↩︎

Case 041083486.2013.3.00.0000 (Mandado de segurança). ↩︎

Brasil, Procuradoria-Geral da República, “STJ Mantém Processo de Demarcação da Terra Indígena Tupinambá, na Bahia,” MPF – Notícias, September 15, 2016. ↩︎

Daniela F. Alarcon, “Doze Anos de Luta pela Demarcação da TI Tupinambá de Olivença,” in Povos Indígenas no Brasil: 2011–2016, ed. Beto Ricardo, and Fanny Ricardo (São Paulo: Instituto Socioambiental, 2017), pp. 713–717. ↩︎

See, for instance, André A. S. Bezerra, “Consenso e Força Perante a Mobilização Tupinambá: O Discurso do Poder dos Meios de Comunicação e do Judiciário” (Ph.D diss., Universidade de São Paulo, 2017). ↩︎

See João Pacheco de Oliveira, “Fighting for Lands and Reframing the Culture,” Vibrant – Virtual Brazilian Anthropology 15, no. 2 (2018): 1–21, Ailén Veja et al., “Those Who Live Like Us: Autodemarcations and the Co-becoming of Indigenous and Beiradeiros on the Upper Tapajós River, Brazilian Amazonia,” Geoforum 129 (2022): 39–48, Alfredo W. B. Almeida, Terras de Quilombos, Terras Indígenas, “Babaçuais Livres,” “Castanhais do Povo,” Faxinais e Fundos de Pastos: Terras Tradicionalmente Ocupadas (Manaus: PGSCA–UFAM, 2008), John C. Comerford, Fazendo a Luta: Sociabilidade, Falas e Rituais na Construção de Organizações Camponesas (Rio de Janeiro: Relume Dumará/Núcleo de Antropologia da Política, UFRJ, 1999) and Lygia Sigaud, “As Condições de Possibilidade das Ocupações de Terra,” Tempo Social 17, no. 1 (2005): 255–280. ↩︎

First called Indian Protection and National Worker Localization Service (SPILTN) and renamed in 1918, it was the first agency devoted to policies for Indigenous peoples created after the proclamation of the Republic. In 1967, it was dismantled following an official investigation that documented widespread corruption and severe violations of Indigenous rights committed by several agency’s employees, in all hierarchical levels. Among others, see Antonio C. Souza Lima, Um Grande Cerco de Paz: Poder Tutelar, Indianidade e Formação do Estado no Brasil (Petrópolis: Vozes, 1995) and the final report of the National Truth Commission which investigated violations of human rights from 1946 to 1988: Brasil, Comissão Nacional da Verdade, “Violações de Direitos Humanos dos Povos Indígenas,” in Relatório, vol. II – Textos Temáticos (Brasília: CNV, 2014), pp. 204–262. ↩︎