Abstract

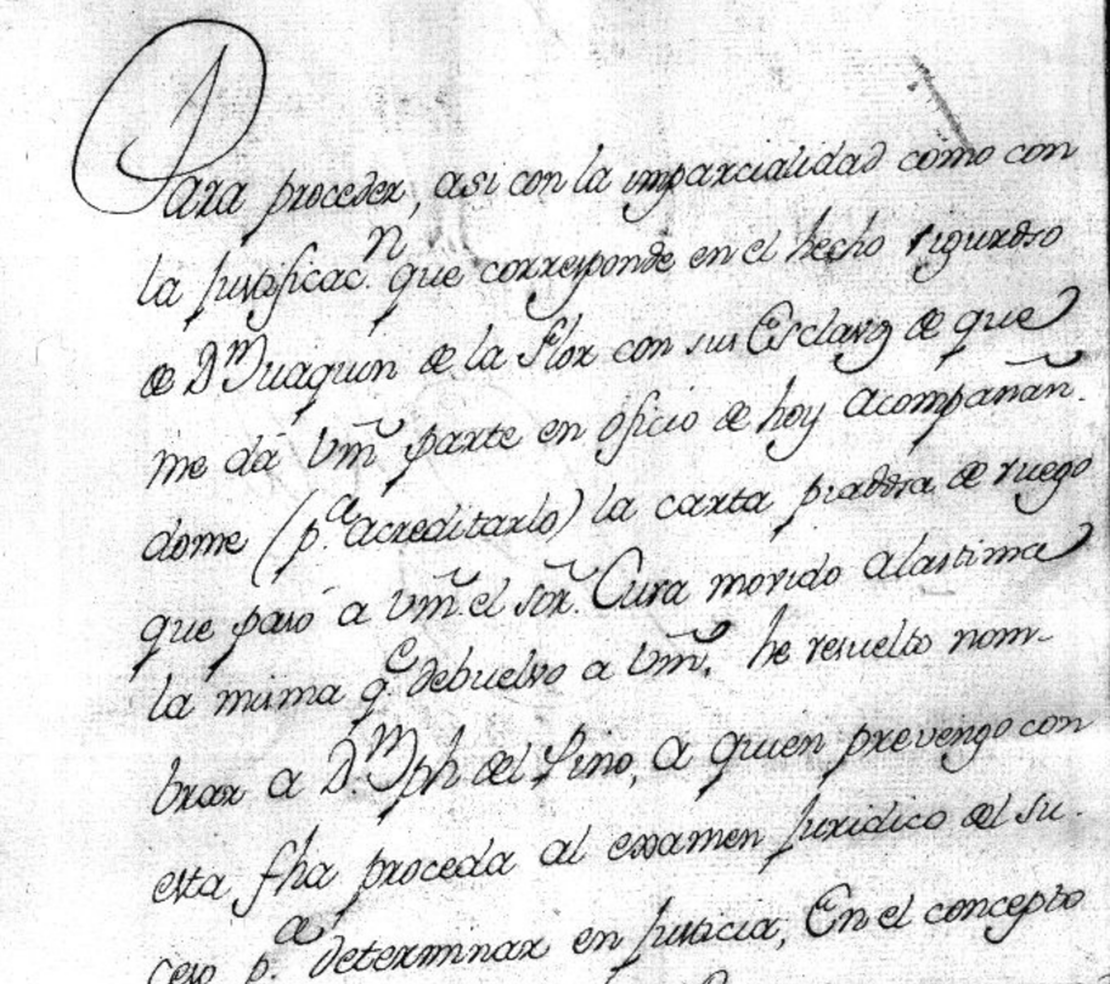

Every generation seeking a shared sense of Colombian-ness must reckon with historical documents that, for many, imply terror, disfigurement, and the erasure of one’s existence as a human being. Archives that speak to national history are also archives of bodily violence. As part of understanding Dispossessions in the Americas, the below discussion includes a Bill of Sale, in 1736, that exemplifies such archives. This essay focuses on what a new generation can grasp by examining the material traces of enslavement. In the present, we can challenge ourselves to reimagine the physical and psychic pain inflicted by some human beings upon others.

People in the present who undertake such reimagining need not feel alone in that effort. Human beings were bought and sold in places we now call home: New York, Galveston, Guanajuato, Kingston, Cartagena, Lima, Bahia, Buenos Aires–and everywhere in between. But throughout the Americas, there are examples of creative people who have examined the pain documented by the archives of transatlantic slavery, taken it up, and then used it in the struggle to change the world’s understanding of our collective past—and of our present.

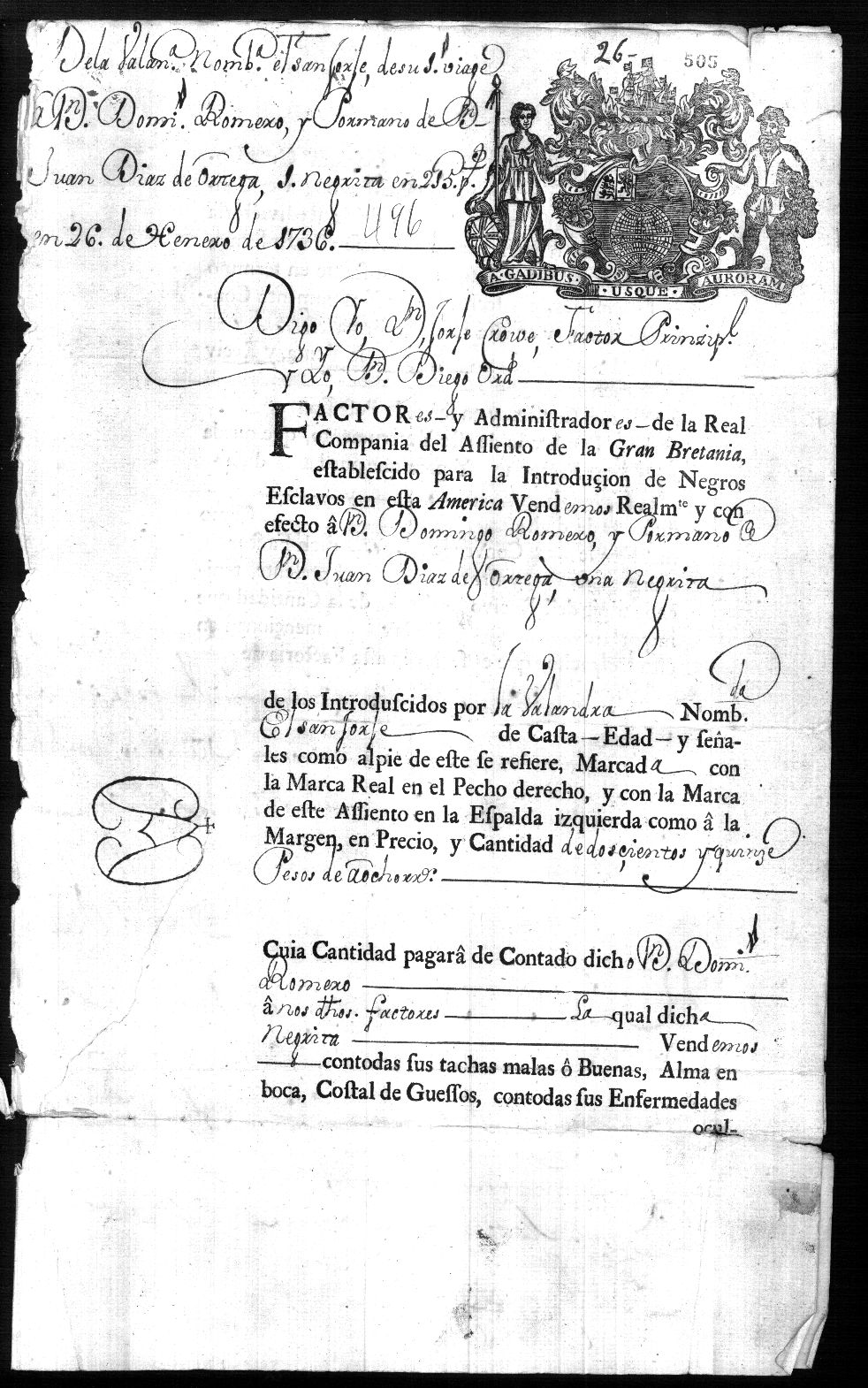

The document transcribed here induces horror in its banal, unfeeling presentation of the fact that, in Cartagena in 1736, a thirteen year-old girl whose skin had been burned with branding irons was sold by a ship’s captain. The shape and meaning of the brands are recorded; her name was not. She is a person who had survived the Middle Passage and then survived being forcibly taken to Bogotá, it seems, as the Bill of Sale was filed with others from Cundinamarca. But historians are unlikely to learn much more about her.

We do know she is represented as being of “Mondongo” ethnicity. Did she end up finding people who spoke her mother’s language or remembered the land she had known before being abducted? Did she tell her own children about different parts of her life and find ways to recreate her personhood? Some in her situation certainly did. Scholars who work with legal cases from the 17th and 18th centuries have found many enslaved women and men who staked claims to freedom. Those who read notarial records see people who bought themselves out of slavery. Research that relies on the history of music, art, and other cultural practices, similarly, demonstrates that enslaved people born in Africa remade the cultural world of the Americas so profoundly that their full humanity cannot be denied. Despite that history of resilience, however, the traumatic pain remains.

For readers who have not looked carefully at Bills of Sale that document enslavement, it may be valuable to pause before undertaking to read through this girl’s transfer, supposedly as “property.” It is worth remembering that she is one person among the approximately 12 million for whom historians have documents proving that they were captured, forcibly transported within African regions claimed by different political actors, violently coerced aboard ships, and sold in the Americas. It is also worth remembering that however painful this history, a long tradition of intellectual and artistic work makes it clear that paying attention to the pain of those enslaved in the past can be part of moving toward a collective process of social, cultural, and political transformation in the present.

Many who have done this intellectual and artistic work are well-known, some less so. Any attempt to suggest the range involved would need to include musicians like Paul Robeson, Bob Marley, Gilberto Gil, Tite Curet Alonso, Susana Baca; poets and writers like Candelario Obeso, Nancy Morejón, Joaquim Machado de Assis, Langston Hughes; and visual artists like Kara Walker, Dalton Paula, Diogenes Ballester. That list includes cultural producers from Brazil, Cuba, Jamaica, Peru, Puerto Rico, and the United States–it could easily be made much longer and point to more national traditions. In Colombia, too, examples abound of Black artists, choreographers, curators, writers, and historians who lay pain before their publics as a way of pushing toward a deeper conversation about racism in the nation’s present.

Turning to the Bill of Sale, the task is not only one of reading but also one of looking carefully at every part of this document. Produced in 1736 as an “instrument” to facilitate sales, it was pre-printed, with spaces left blank so that those involved in the entirely “legal” practice of buying and selling of human beings could fill in their own names and sometimes also the names of enslaved persons. It is worth noticing that the printed words are carefully truncated to allow for endings to be correct in gender and number, and that additional blank lines were added where the seller might write in identifying information for several people. Physical and emotional pain leap off the page.

“Factura de Venta,” 1736. In Caja Negros y Esclavos Cundinamarca, Tomo 8, Folio 505R, Archivo General de la Nación, Bogotá, Colombia.

Please note that the below transcription retains line breaks in the original and uses the somewhat arbitrary conventions of italics to indicate script and bold font with underlining to indicate pre-printing. Accents and spelling are somewhat modernized. Note also that Ana María Gómez López has translated the text to read more like an English-language Bill of Sale from the same period and less like a literal translation; it is also not line-by-line.

De la Valan[dra] nomb[rada] el san Jorge, desu 1[er]. Viaje Factor es y Administrador es de la Real Compañía del Assiento de la Gran Bretania,

efecto â Dn. Domingo Romero, y Pormano de Don Juan Díaz de Ortega, una negrita de los Introducidos por La Valandra Nomb.[rada] El San Jorge de Casta–Edad–y seña- les como al pie de este se refiere, Marcad a con â nos, [dichos] factores_________ La qual dich a Negrita_______________ Vend emos ______ con todas sus tachas malas ô Buenas, Alma en —--------------------------------------------------------------- ocultas, y Manifiestas, Ezept amos solamente Gota Co- del Esclavo, ô Esclavos que tuviese esta Enferme- dad, seha de hazer notoria y Constante en término de Dos messes de la fecha de este Ynstrumento Con- forme al uso, y en esta referida forma Yo, Don Dom. Romero______ acepto la Venta, y Recib o La dich a negrita___________________________ y para que Conste, y en señal de Posessión he firmado Duplicado de este Ynstrumento, que queda en la Real Factoría. Y para que pued a dich o otorg amos y firm amos ____ el presente, teni- endo alpie de'l Recibo del Factor__ de la Cantidad que importare la__ Esclav a mencionada en este Despacho, que es fecho en esta Factoría de Cartagena de Yndias en veinte y seis de Henero de mill setezientos y treinta y seis siendo Jorge Crowe Diego Ord Reze[vido] de Don Domingo Romero y Pormano de Don Juan Díaz de Ortega los doscientos y quinze [pesos] de la negrita, contenida en este despacho, y Para que conste lo firmé en 26 de Hen[ero] de 1736. Jorge Crowe |

On January 26, 1736, I, Jorge Crove, Principal Factor, and Don Dom. R, Factors and Administrators of the Royal Company of the Asiento of Great Britain, established to introduce Black Slaves to this America, do Lawfully and with immediate effect Sell to Don Domingo Romero, from the hand of Don Juan Díaz de Ortega, a black girl Brought by the vessel called the Saint George, of Caste ____, Age ____, and markings referred to below: bearing the Royal Mark on her right breast and the Mark of this Asiento on the left side of her back, as shown in the Margin; for the price and quantity of two hundred and fifteen pesos of eight reales. Said sum will be paid in full by the aforesaid Don Domingo Romero, to us, Aforesaid factores ____, who sell the aforesaid black girl with all of her qualities, bad or good, Soul in mouth, Bag of bones; with all her Illnesses, hidden and Manifest, with the sole exception of Gota Coral, or by another name heart disease. In order to validate a Slave Warranty for slaves that have this illness, it is a Condition that official notice and documentation be Provided within two months from the date agreed in this instrument, and it is in this stated manner that I, Don Domingo Romero, accept the sale, and receive the aforementioned black girl, and in proof and confirmation of this possession I have signed a duplicate of this instrument, which will remain in the Royal Factoría. And in order for the aforesaid Don Domingo Romero to dispose of said black girl as he sees fit, we the aforesaid factores concede to and sign this document, the Factor having received the amount for the import of the slave mentioned herein, held in this Factoría of Cartagena of Indies on January 26, 1736, being the black girl included in this deed of sale, of Mondongo caste, thirteen years of age, with three incisions running parallel along the skin on her stomach, [Signed] Jorge Crove Diego Ord I received from Don Domingo Romero and from the hand of Don Juan Díaz de Ortega two hundred and fifteen pesos for the little black girl, and have signed in confirmation of this on January 26, 1736. [Signed] Jorge Crove *Translation by Ana María Gómez López |

It is because of documents like this one that the professional historian Sergio Mosquera, who was born in Istmina, and who founded the Muntú Bantú Memory Center for Documentation and Afrodiasporic Materialities in Quibdó, asked local blacksmiths to recreate a set of branding irons, complete with a mock-up brazier. When taking school groups, college interns, and others through the space, he points out the coals he has included in the installation since conceiving it in 2015. Mosquera’s purpose is to have visitors reflect upon the physical trauma enslaved people were forced to endure in addition to their psychic pain.

Colombian contemporary artists working in many different forms of media engage in a similar practice. 20 years ago, Liliana Angulo, a photographer and performance artist who now (in 2024) serves as the director of Colombia’s National Museum, produced—twenty years ago—a wide range of different kinds of self-portraits that explicitly commented on racism in the country from different temporal positions. Among these was a color photograph of her with an iron shackle around her neck—demanding that Colombians recognize a collective past predicated on African enslavement. More recently, the Cali-based artist Fabio Melecio Palacios produced a series of wall sculptures in the form of over-sized brands, directly referencing archival documents and his own visit to the island of Goreé, in Senegal. In recreating shapes that had been burned onto the skin of enslaved people, Melecio used discarded razor blades as a way of tying together past and present. He was explicit about wanting viewers and gallery visitors to realize that these were still shapes that evoked woundings, blood, pain: Approach them at your peril, his work forewarns.

The original document is housed in the fond “Negros y Esclavos” of Colombia’s National Archives, sub-fond for Cundinamarca, as indicated above. It is a place Colombian scholars look to as they wrestle with what a past marked by enslavement means in each new generation. Indeed, this same Bill of Sale, along with others, appears in an essay included in a field-defining book titled “I Demand My Liberty: Black Women and their Resistance Strategies in New Granada, Venezuela, and Cuba.” One of the co-editors is Aurora Vergara Figeroa, who now (in 2024) serves as Colombia’s Minister of Education. Now, in the early decades of the 21st century it is more than ever true that none of us need confront the archives alone.

Further reading:

Bosa, Bastien, Diana Angulo, Ingrid Frederick, and María Clara Quiroz. Solo cicatrices: Carimbas de la trata transatlántica. Universidad del Rosario, 2023.

Farnsworth-Alvear, Ann, Marco Palacios and Ana María Gómez López, eds. The Colombia Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

Fernando Gómez Echeverrí. “La exposición de Fabio Melecio Palacios en Espacio El Dorado trae al presente un pasado infame,” El Tiempo, June 30, 2023, https://www.eltiempo.com/cultura/arte-y-teatro/fabio-melecio-palacios-la-historia-de-un-hombre-carimbado-782418

Gómez, Pablo F. “Pieza de Indias,” in New World Objects of Knowledge: A Cabinet of Curiosities, edited by Mark Thurner and Juan Pimentel. University of London Press, 2021*.*

Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12, no. 2: (2008): 1–14, doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/-12-2-1

Mosquera Mosquera, Sergio A. *La carimba: La carimba candente. La carimba sobre la piel.

*Serie Ma’mawu. Vol. 8. Universidad Tecnologica del Choco. 2003.

Pena Mejía, Adriana. “Negra menta: Por un reconocimiento a la mujer afrocolombiana.” Artelogie 9 (2016) https://doi.org/10.4000/artelogie.322

Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12, no. 2: (2008): 1–14, doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/-12-2-1.

Pena Mejía, Adriana. “Negra menta: Por un reconocimiento a la mujer afrocolombiana.” Artelogie 9 (2016) https://doi.org/10.4000/artelogie.322.

Reyes Castriela Esther Hernández. “Aproximaciones al Sistema de Sexo/Género en la Nueva Granada en los Siglos XVIII y XIX,” in Demando Mi Libertad: Mujeres Negras y Sus Estrategias de Resistencia en La Nueva Granada, Venezuela y Cuba, 1700-1800, edited by Aurora Vergara Figueroa and Carmen Luz Cosme Puntiel. Editorial Universidad Icesi, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/jj.5329457