Abstract

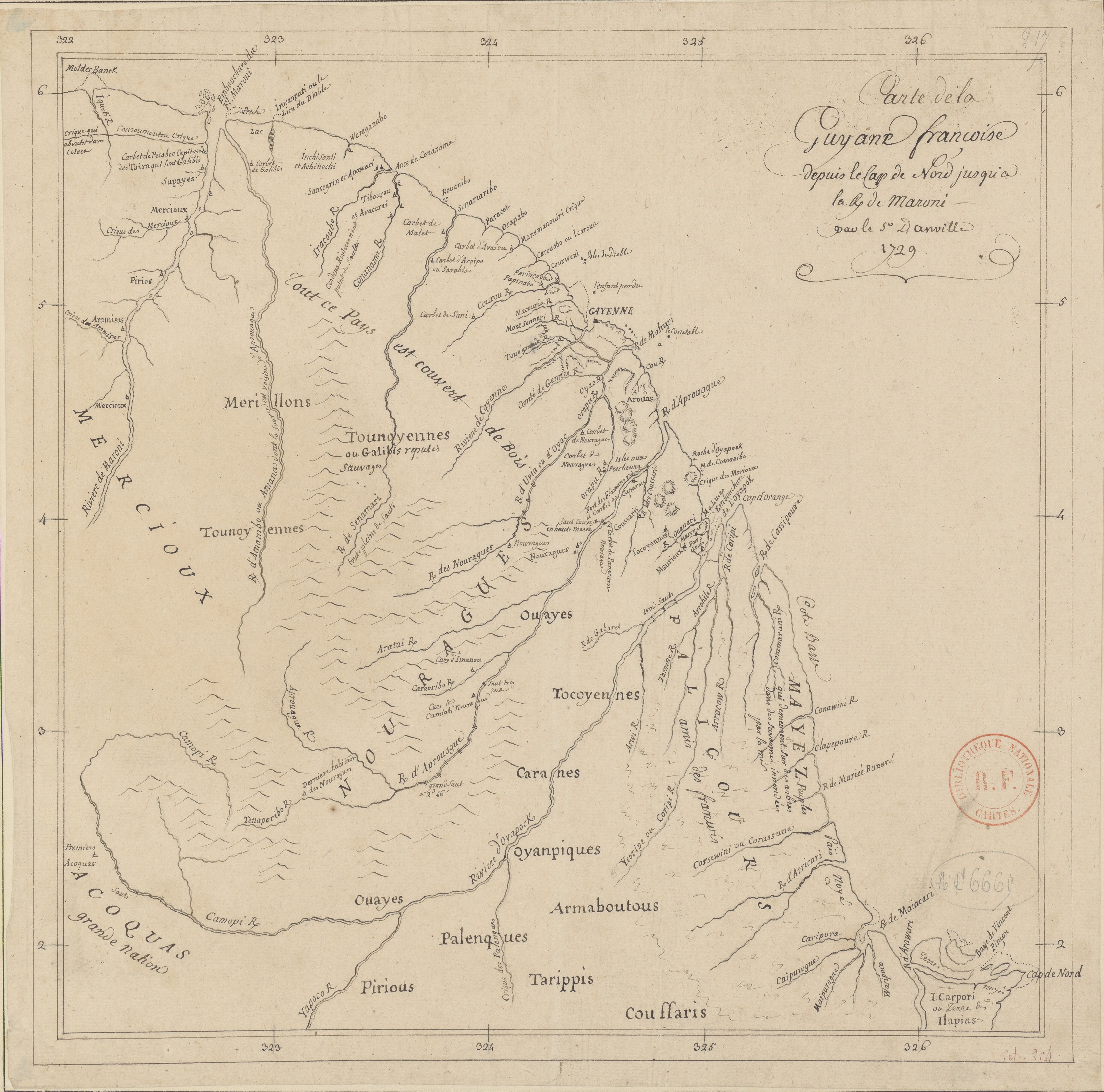

More accurate maps of French Guiana appeared after French colonial power secured its dominion in Cayenne. Their influence expanded through the coast, from the city to the Maroni River. One of the most remarkable representations of the claimed territory is the one made by the cartographer Jean-Baptiste D’Anville (1697-1782) in 1729.

The work of D’Anville contributed to the renovation of European geography and cartography. His success resulted from combining multiple sources, contrasting with first-hand testimonies, and relying on astronomical observation. D’Anville’s work took place within strong networks of patronage and scientific collaboration. He worked on weaving a robust correspondence in the Republic of Letters and contributed to journals and newspapers to increase the visibility of his cartographical and geographical studies.1

D’Anville’s 1729 map of Guiana had several reproductions, both printed and manuscript.2 The description of the Indigenous people allows us to trace their movement in the territories. It is noticeable their displacement from the Atlantic coast to the inner lands.3 Some new Indigenous people’s identifiers also appeared. The map presents the “Mérillons” (or Émérillons), a way French explorers would name the Teko people until the late 20th century. The same will be valid for the “Oyanpiques” (or Oyampis), today recognized as Wayāpi. At this point, most of the previously documented names of the Indigenous people appear on the map, such as the Acoquas, Aravacas, Armaboutous, Arouas, Coussaris, Galibis, Maïez, Mercioux, Nouragues, Palicours, Pirious, Supayes, Tocoïeunes, Tounoïennes, and Yayos. D’Anville will include three new denominations: the Aramisas, Caranes, and Ouayes.

D’Anville’s map not only offers new naming of the Indigenous people but also descriptions and commentaries. For example, the map includes comments on the physiognomy of the Indigenous people. D’Anville records how the Armaboutous (today identified as the Titiyó) used to have “long ears hanging over the shoulders and several holes on the face.”4 He also traced the movement and location of Indigenous people, as when placing the “last dwelling of the Nourages” or describing the Mayes as “those who live on the trees in the savanna drowned by the sea.” Additionally, there are several commentaries on the Indigenous people and their relations with the colonizers, such as when saying that the Tounoyennes (Wayana) and Galibis (Kali’na) are “reputed as savages;” or the Palicours (Paykweneh) are “friends of the French.”

D’Anville launched a renovation of the cartographic practice and the representation of the Earth. However, it is necessary to emphasize how most of these maps were made by someone who never left Europe. Consequently, the 1729 map includes a disclaimer recognizing how most of the available information resulted from the Jesuit exploration of 1674. Hence, cartographers such as D’Anville received updated accounts of the territory, which they contrasted with other maps and evaluated based on astronomical observations.5 His renown and celebrity as a cartographer allowed him to access fundamental materials for his works. This situation does not imply he transposed the information verbatim from the sources to his maps, but he used his knowledge to entangle the sources critically.6 Moreover, he left detailed essays about the process of crafting his maps and a deliberated purpose of abandoning doubtful information.7

Map citation:

Jean-Baptiste D’Anville. Carte de la Guïane françoise ou du gouvernement de Caïenne depuis le Cap de Nord jusqu’àla rivière de Maroni inclusivement, Map 40 x 49 cm. S.l., 1729. Bibliothèque National de France – Gallica. Accessed August 12, 2023. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b85967714

Lucile Haguet, « Un discours de légitimation du géographe et de la géographie par la renommée et la célébrité : l’exemple de Jean-Baptiste d’Anville (1697-1782), » Revue de géographie historique 17-18 (2020), paragraphs 2, 36-44. ↩︎

Each new version will include subtle differences, for example, in FGU0023, there is less information about Indigenous communities, which suggests a different purpose for the map. ↩︎

The map locates the following groups: Acoquas; Aramisas; Aravacas; Armaboutous; Arouas; Caranes; Coussaris; Galibis; Maïez; Mercioux; Mérillons; Nouragues; Palicours; Pirious; Ouayes; Oyanpiques; Supayes; Tocoïeunes; Tounoïennes; Yayos ↩︎

This nation has several denominations across the maps, including Aramagotos, Aramacotos, or Kirikiricotos. ↩︎

Haguet, “Un discours de legitimation,” paragraph 5; Pimentel Cintra, Ferreira Furtado, “A Carte de l’Amérique Méridionale,” 295-300. ↩︎

Jorge Pimentel Cintra, Júnia Ferreira Furtado, “A Carte de l’Amérique Méridionale de Bourguignon D’Anville: eixo perspectivo de uma cartografia amazônica comparada*,*” Revista Brasileira de História 31, no. 62 (December 2011): 274-277, 284-286. ↩︎

Lucile Haguet, “Specifying Ignorance in Eighteenth-Century Cartography, a Powerful Way to Promote the Geographer’s Work: The Example of Jean-Baptiste d’Anville,” in The Dark Side of Knowledge: Histories of Ignorance, 1400 to 1800 edited by Cornel Zwierlein (Leiden: Brill, 2016). 373. ↩︎