Abstract

The following essay offers some insights into land tenure and the deracination of Afro-descendant Black communities in Colombia. It analyses the collective purchase of 50 hectares of land made by 15 people in the 20th century in Peón, Valle del Cauca region, to avoid dispossession. First, it introduces a theoretical approach to the concepts of collective land tenure and deracination. Next, it provides an in-depth review of the deed by which the people became landowners. Finally, it offers some conclusions on what this acquisition means for the collective land tenure of Afro-descendant communities in Colombia.

What does Collective Land Tenure and Deracination Refer to? 1

Land tenure is understood as “the right to the use of land, which refers to the physical possession of a property regardless of the legitimacy of the owner.” (Cruz et al, 2018, p. 9). In other words, land tenure taps into the possibility (or impossibility) of people owning land. When addressing the ownership of those who occupy land and those who claim it —who could be the same individuals or not—, historical, political, social, cultural, and economic factors are involved that influence the decisions made on the land itself. When looking at the Colombian context, the adjective “collective” adds accuracy to the land rights claimed by ethnic groups. Since land occupation and the connection with the inhabited territories are mediated by the ethnic condition, “collective tenure” is linked to worldviews and ancestry. As a result of the demands over land tenure of these groups, the nascent Republic gave way to the enactment of Act 25 of 1824, which legislated respect for the territorial ownership of Indigenous peoples. However, the so-called Black communities did not engage in the legislative processes of the time, possibly because slavery had not been abolished (1851) and they were not considered citizens with rights.

The 1991 Political Constitution brought about a major change in land tenure in Colombia. The new legislation transformed the State’s view of peoples formerly considered Indigenous and tribal into that of “ethnic groups.” In Article 7, the Colombian State made a pledge not only to recognize but also to protect the nation’s ethnic and cultural diversity. Since then, “indigenous reservations are considered territorial entities with their own authorities, performing administrative functions [while] Afro-descendant communities are established as collective subjects bearing rights and obligations (Velásquez, 2017, p. 2 y 3).” However, the constitution still failed to address the demands of the Black communities. This situation prompted the temporary enactment of article 55, which ruled the need for an act specifically drafted for this group. These efforts gave way to Act 70 in 1993, which defined concepts such as “collective occupation”, understood as “the historical and ancestral settlement of Black communities in lands that constitute their habitat for their collective use, and on which they may carry out their traditional production practices” (Congress of Colombia, 1993). This act stood as a significant step forward for Black communities since their right to collective ownership had been acknowledged for the first time. It is indeed a shift of key relevance for communities that had so far occupied the vacant land in rural areas along the banks of the rivers of the Pacific Basin.

Regarding deracination, intellectuals such as Santiago Arboleda (2007) and Aurora Vergara Figueroa (2018) agree that concepts such as displacement or forced migration are not adequate to embrace the characteristics associated with the historical mobility of racialized human beings since the colonial period. For Arboleda (2007), exile means an “extended relentless uprooting” and is —indeed— the reason for the impoverishment on social, cultural, and economic terms of Afro-descendant communities in Colombia. In turn, Vergara (2018) states that the concepts forced migration and forced displacement do not offer a satisfactory explanation to fathom how nations and populations that share similar histories of racialization, conquest and domination are the focus of old and new modes of diasporic exile. The author poses the urgency of a geohistorical analysis of exile, which resorts to exile and diaspora as analytical categories in an extensive process of land tenure and territorial construction prior to dispossession. Thus, she places “contemporary forms of exile in a chain of historical processes: transatlantic trade, African diaspora, territorial settlement in the Colombian Pacific (territorialization), 20th century deracination, a new cycle of diaspora and new territorial settlements” (Vergara, 2018, p. xviii). Considering the former, the author puts forth the D-T-D matrix (Diaspora-Territorialization-Deracination/Diaspora) as an explanation for the complexity of historical settlement and mobility processes that other categories have been unable to interpret. The theoretical contributions offered by both intellectual thinkers are essential to understanding Peón´s collective purchase in relation to land tenure in Colombia, as this case allows us to illustrate old and new forms of deracination of the African diaspora.

Collective Land Purchase in Peón to Prevent Deracination

In 1939, in Valle del Cauca region, 15 individuals were part of a milestone for the collective land tenure of Afro-descendant communities in Colombia. 54 years before the enactment of Act 70 for Black Communities in 1993, these people made the courageous decision to collectively purchase land. More specifically, we are referring to a group of people whose ancestors and ancestresses were considered property in a slave system that lasted nearly four centuries, who in 1939 became landowners. According to accounts by the elders, the purchase was a strategy to avoid being deracinated, since foreigners had already arrived with documents claiming to be the owners of the lands where the 15 individuals lived with their families. Deed 526 dated June 9, 1939, ratifies this event. Namely, for a value of $100 (100 Colombian pesos), Isaías Sánchez A.

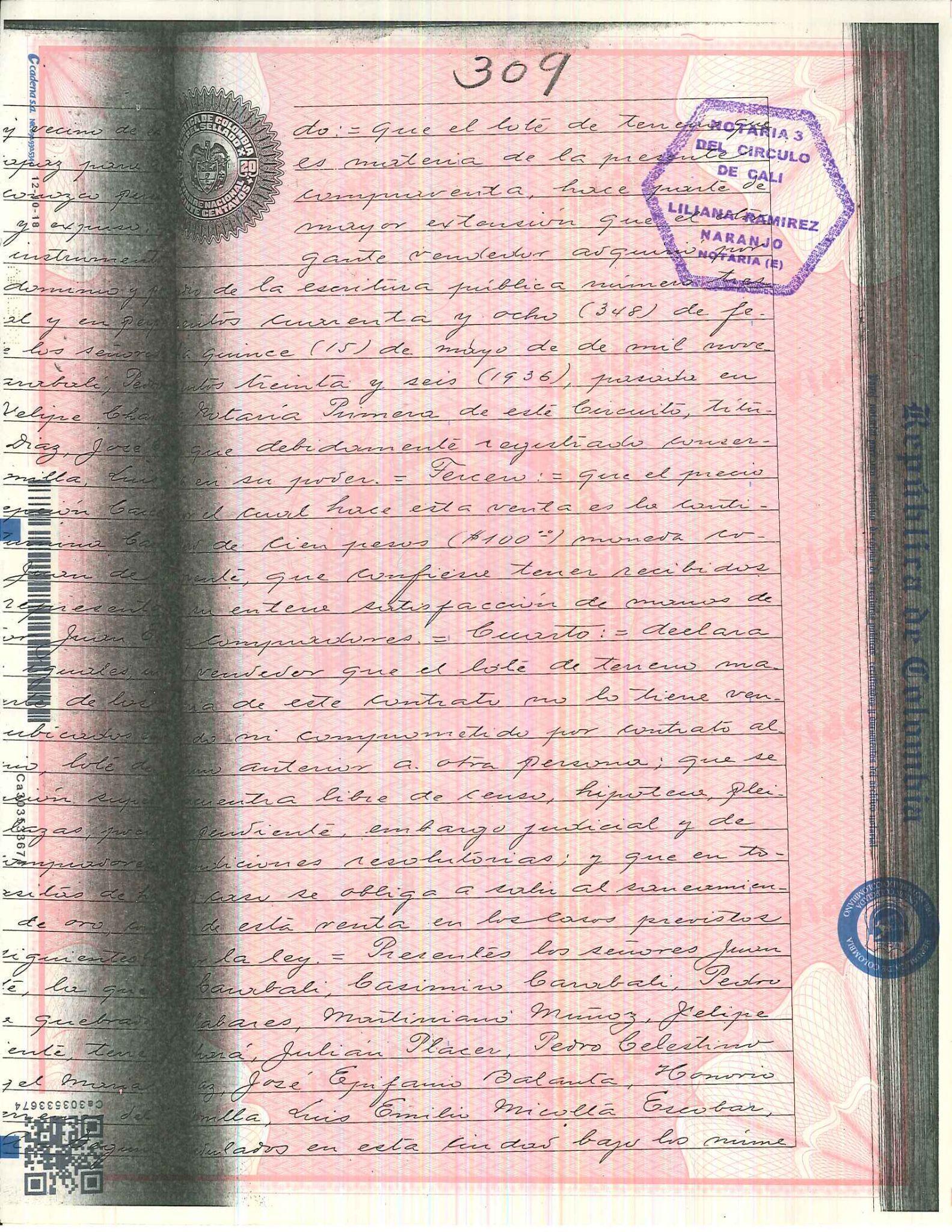

(…) transfers full ownership and possession by way of sale in rem and in perpetual alienation in favor of Messrs. Juan E. Carabalí, Casimiro Carabalí, Pedro Ulabares, Martiniano Muñoz, Felipe Chará, Julián Placer, Pedro Celestino Díaz, José Epifanio Balanta, Honorio Bonilla, Luis Emilio Micolta Escobar, Concepción Caicedo, Ana María Ulabares, Saturnina Carabalí, and of minors Juan de Dios Carabalí and Pedro Díaz, represented herein by Mr. Juan Carabalí; in equal parts a lot of land, which is part of the land called Peón, located in the jurisdiction of this municipality, a plot with a surface area of —approximately— 50 squares, where the buyers have agricultural crops and small houses and also a gold washing place […] (Notaría tercera de Cali, 1939).

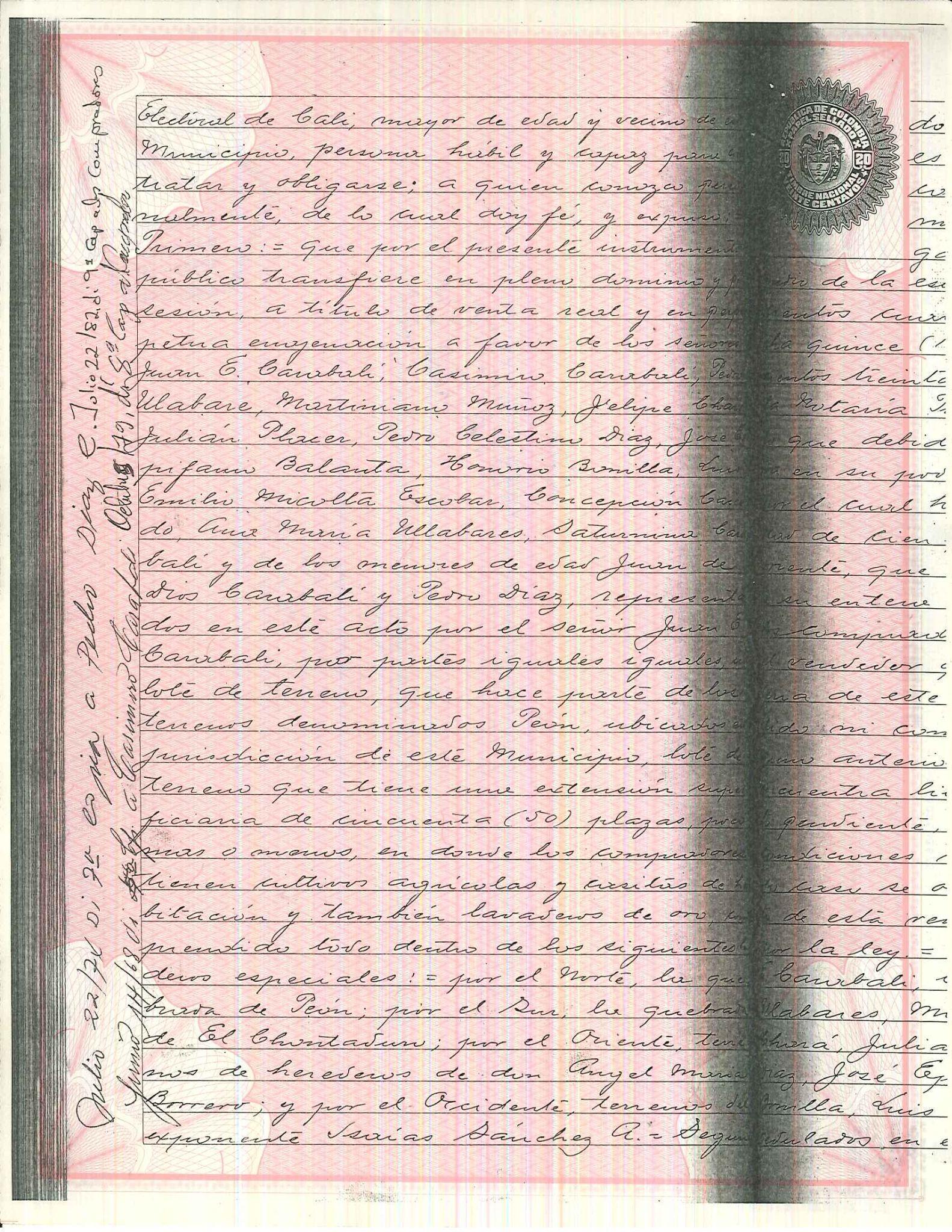

The first page of the file displays the information corresponding to the number, the date on which this event was conducted, the place, the name of the notary, the witnesses, and the seller. There is also a note on the left margin indicating the date on which a copy of the document was taken and who it was given to (please, see illustration 1). Page 2 states the names of the individuals who participated in the purchase (please, see illustration 2). It is worth highlighting that, according to several authors (D. Pavy, 1967 in Mina, 1975; Pérez, 1989; Uribe, 2014; Zapata, 1989, 1990, 2007), surnames such as Carabalí and Balanta were ways of naming some people who had been kidnapped and brought from Africa to the lands of present-day Colombia to be subjected to enslavement. In the same manner,

As per the interviews conducted, almost all of the inhabitants of Chontaduro mining region belonged to families with surnames of African origin formerly mentioned [Viáfara, Carabalí, Amu, Mulato] who had been evicted from their former possessions by a family of Antioquians, who bought Hacienda Chontaduro, extending their domain to the ravine bearing the same name, and moved to another ravine located further south, called La Mina, near the present township of Potrerito. (Popo, 1988, p. 67).

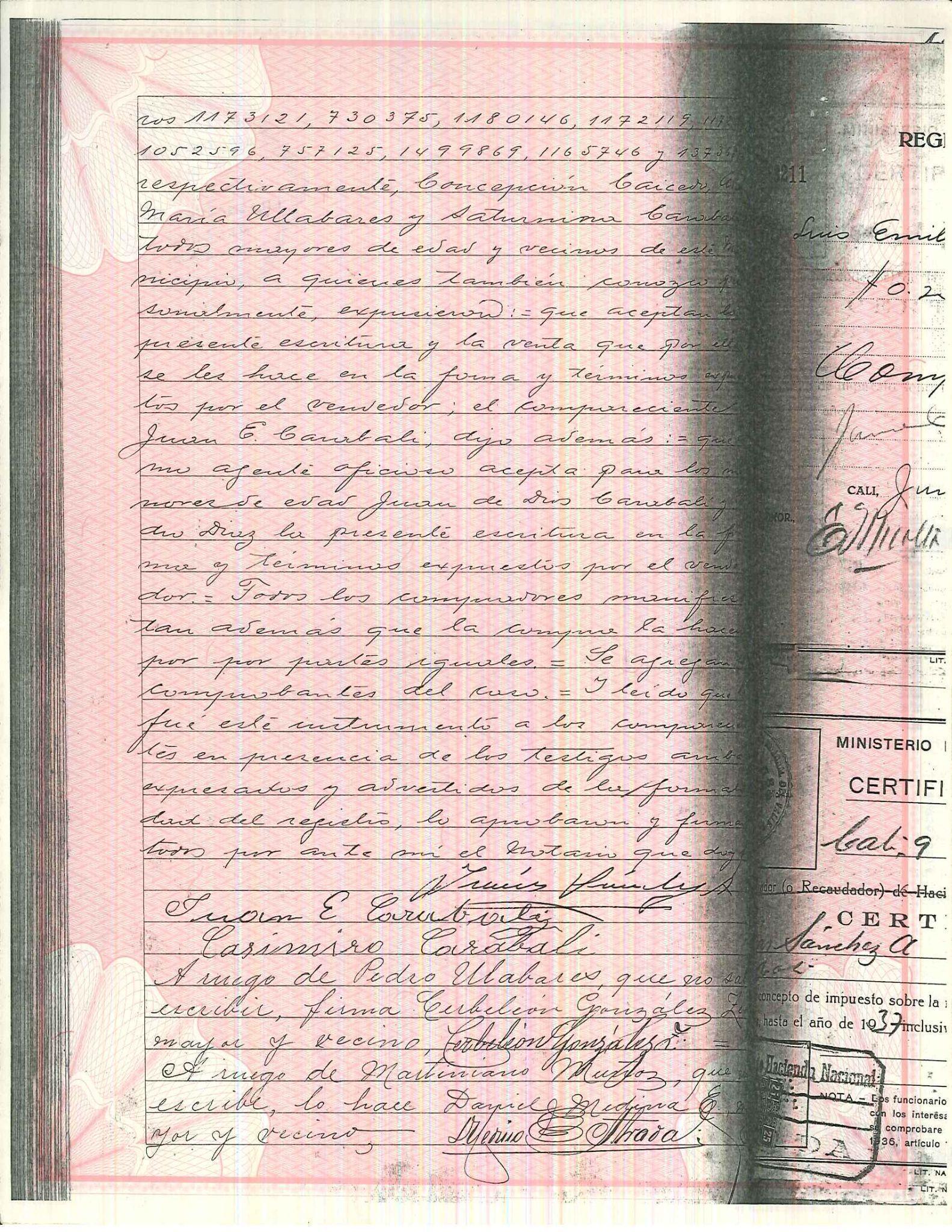

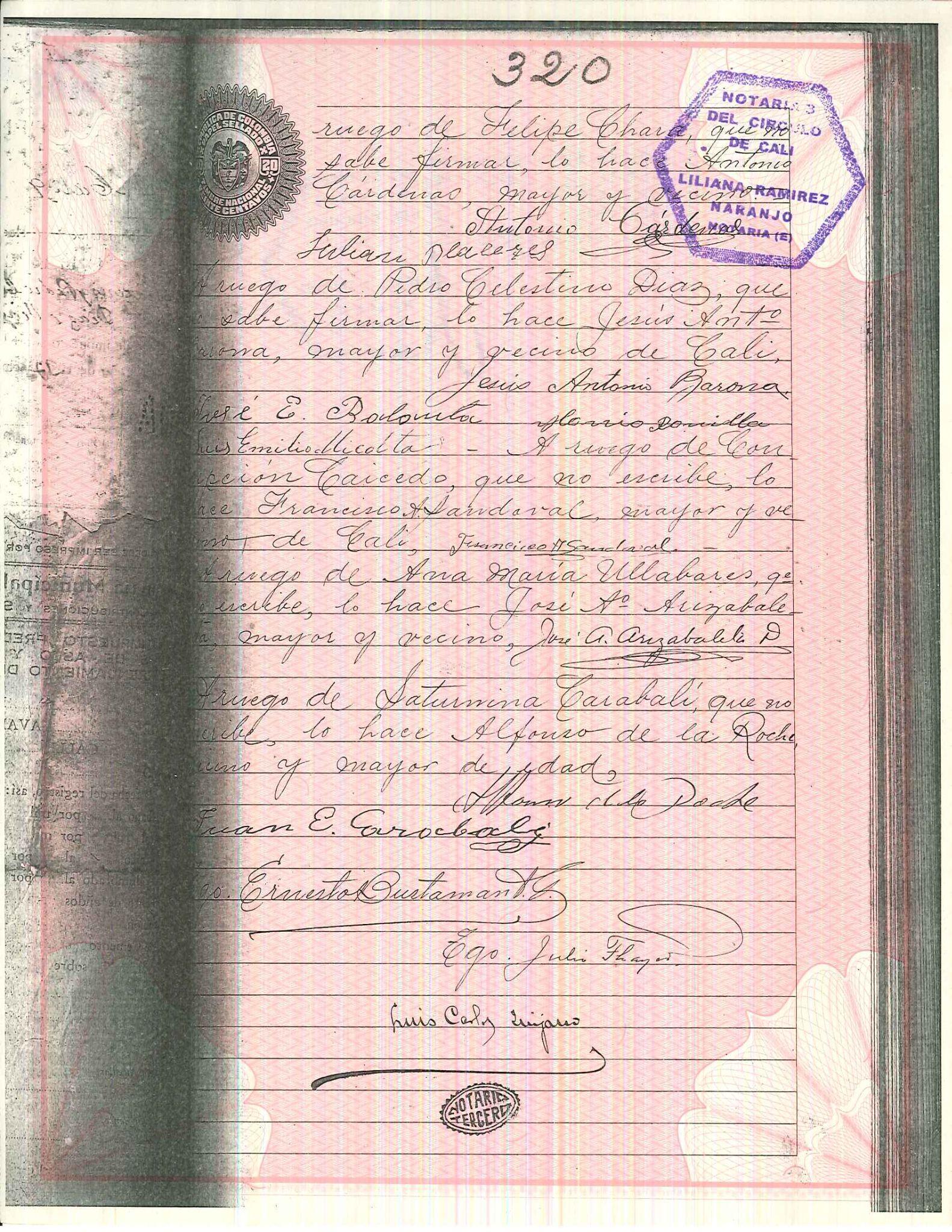

The third page of the deed (please, see illustration 3), reads that the lot that Isaías Sánchez sold to the buyers was part of a larger plot, “that the grantor-seller acquired by means of public deed number three-hundred and forty eight (348) dated May fifteen (15), of nineteen hundred and thirty six (1936), held in the first Notary Office of this circuit, title duly registered in his possession” (Notaría tercera de Cali ,1939). Upon reading this part of the file, the following question arises: how was it possible that Isaías Sánchez may have acquired lands three years before selling them to the buyers of Peón when these already had crops, houses and places for gold washing there? Page four of the deed (please, see illustration 4) interestingly mentions that “all the buyers additionally state that the purchase is made in equal parts” (Notaría tercera de Cali. 1939).

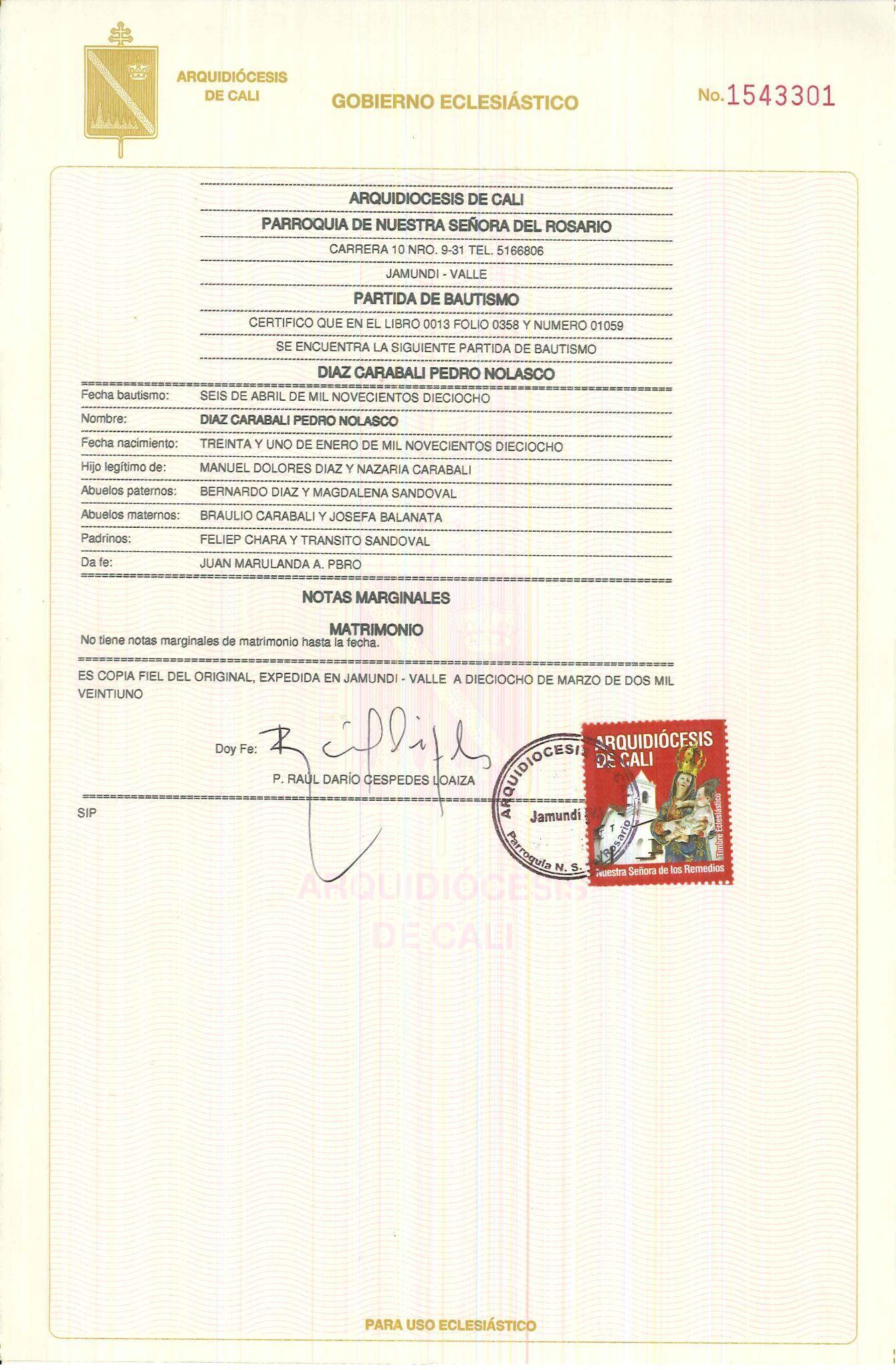

The presence of three women in this deed is an aspect worth noticing. Namely, Concepción Caicedo, Ana María Ulabares, and Saturnina Carabalí. At this time, voting or women’s suffrage had not yet been passed in Colombia2. The impossibility of voting meant not having a personal electoral card for women to identify themselves. Only the baptismal, marriage, and death certificates or the official birth certificate were valid for legal and civil purposes. Moreover, according to the deed, none of the three women could write. Even so, their names appear on the document. The engagement of these women in the collective purchase suggests that it was a collective community agreement characterized by the inclusion of ever member, regardless of gender.

Illustration 1. Page 1, Public deed 526 dated June 9, 1939. Source: Notaría tercera de Cali, Colombia.

Illustration 2. Page 2, Public deed 526 dated June 9, 1939. Source: Notaría tercera de Cali, Colombia.

Illustration 3. Page 3, Public deed 526 dated June 9, 1939. Source: Notaría tercera de Cali, Colombia.

Illustration 4. Page 4, Public deed 526 dated June 9, 1939. Source: Notaría tercera de Cali, Colombia.

The exact date as of when the 15 people settled on the land they bought from Isaías Sánchez is unknown. However, the years and places of birth of Pedro Nolasco Díaz Carabalí and Josefina Carabalí Viáfara —relatives of several of the buyers— help determine the presence of the latter in that area at least since the beginning of the 20th century. Pedro Nolasco stated that he had been born in Chontaduro —location adjacent to Peón—, in 19083. Josefina said she had been born in Peón in 1928. According to other accounts from elders of Peón who are alive today, some individuals like Pedro Nolasco Díaz Carabalí, José Epifanio Balanta Mosquera, Maximina Carabalí Mulato, Pedro Antonio Ulabares, and María Francisca Carabalí Posú had been born in Chontaduro or Peón. Those who died in Chontaduro were even buried there, since they had built their own cemetery in the area.

Illustration 5. Page 5, Public deed 526 dated June 9, 1939. Notaría tercera de Cali, Colombia.

Illustration 6. Baptismal certificate belonging to Pedro Nolasco Díaz Carabalí. Source: Nuestra Señora del Rosario Parish (Jamundí), Archdiocese of Cali, Colombia. Copy issued in 2021.

To conclude

Historically, the land tenure of Afro-descendant Black communities in Colombia has not only been expressed in the constitution of palenques and in the adjudication of vacant land, but also in collective purchases. Along with Act 70 of 1993, specifically in Chapter III, Recognition of Collective Property, legal progress was made in granting legitimacy to the rights of these communities associated with tenure. In particular, collective occupation represents a gain in access to and ownership of land.

The collective purchase of land in Peón is a very compelling case. Within this underlying power, the narrative and discourse of collective occupation and territorial construction account for land tenure mechanisms implemented by the Black community, ranging from their relationship with the physical space to their forms of community organization. This milestone casts light on little known strategies to address and prevent deracination, securing the livelihoods of these communities. The case of Peón is critical to offset the idea of passive inaction of Black people in Colombia. The analysis of this collective purchase in the 20th century represents an empirical and theoretical challenge for qualitative research in social, cultural and Afrodiasporic studies. Additionally, it contributes to the identification of new elements that define land use and tenure processes in Colombia.

References

Documentary Sources

Archdiocese of Cali (2021). Nuestra Señora del Rosario Parish (Jamundí). Baptismal certificate belonging to Pedro Nolasco Díaz Carabalí dated 1918.

Notaría tercera de Cali. Public deed 526 dated June 9, 1939.

Secondary Sources

Arboleda Quiñonez, S. (2007). Conocimientos ancestrales amenazados y destierro prorrogado: la encrucijada de los afrocolombianos. En: C. Mosquera Rosero- Labbé y L. C. Barcelos (2007) (Eds.), Afro-reparaciones: Memorias de la esclavitud y justicia reparativa para negros, afrocolombianos y raizales. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Retrieved in April of 2022 from: https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/bitstream/handle/unal/2862/17CAPI16.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y

Congress of Colombia. (1977). Act 27 by which the legal age is set at 18 years old. Retrieved on October 15, 2022 from: https://www.icbf.gov.co/cargues/avance/docs/ley_0027_1977.htm

Congress of Colombia (1993). Ley 70 de 1993, Por la cual se desarrolla el artículo transitorio 55 de la Constitución Política. Retrieved in March of 2022 from: https://pruebaw.mininterior.gov.co/sites/default/files/30_ley_70_1993.pdf

Cruz, C., Dussán, C, Gaitán, J. y Callejas, W. (2018). Reflexiones sobre el problema de tenencia de tierras y la seguridad alimentaria en Colombia. (Documento de trabajo N° 3). Bogotá: Ediciones Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia Press. Retrieved on October 7, 2022 from: https://repository.ucc.edu.co/bitstream/20.500.12494/10856/1/2018_AV_Reflexiones_Cruz.pdf

Mina, M. (1975). Esclavitud y libertad en el Valle del río Cauca. Retrieved in 2021 from: https://vertov14.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/mateo-mina-libertad-y-esclavitud-en-el-valle-del-cauca.pdf

Pérez Ramírez, G. (1989). Mirar hacia Africa. Bogotá, Colombia: Plaza & Janes

Popo, R. (1988). La disolución de las tierras comunales. El caso del indiviso de Jamundí. [Undergraduate monograph presented as a partial requirement for the degree in Sociology]. Cali, Colombia: Universidad del Valle.

Registraduría Nacional del Estado Civil. (s.f). Historia de la identificación. Retrieved in March 2022 from: https://bit.ly/3xtZW39

Registraduría Nacional del Estado Civil. (s.f). El día que las mujeres votaron por primera vez. Retrieved in March, 2022 from: https://www.registraduria.gov.co/-El-dia-que-las-mujeres-votaron-por-.html

Senado y Cámara de representantes de la Nueva Granada. (1851). Ley 2 de 1851 sobre libertad de esclavos. Retrieved in March, 2021 from: https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=12623

Uribe, D. (2014). África nuestra tercera raíz. Bogotá, Colombia: Aguilar.

Vergara Figueroa, A. (2018). Afrodescendant Resistance to Deracination in Colombia. Massacre at Bellavista-Bojayá-Chocó. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave McMillan.

Velásquez Ruiz, M. A. (2017). La tenencia colectiva de la tierra en Colombia. Antecedentes y estado actual. Retrieved in May 2021 from: https://doi.org/10.17528/cifor/006684

Zapata Olivella, M. (1989). Las claves mágicas de América. Bogotá, Colombia: Plaza & Janes.

Zapata Olivella, M. (1990) ¡Levántate mulato!: “Por mi raza hablará mi espíritu”. Bogotá, Colombia: REI ANDES LTDA.

Zapata Olivella, M. (2007). Changó el gran putas. Bogotá, Colombia: Educar Publishers.

This essay is part of the book entitled “Propietarias: Historia del territorio Peón (Valle del Cauca, Colombia) 1939-2005”, as the outcome of the homonymous research I conducted while pursuing my Master´s degree in Social and Political Studies at the Universidad Icesi. Propietarias is currently under editing for publication. ↩︎

For more information, please, visit: https://www.registraduria.gov.co/-El-dia-que-las-mujeres-votaron-por-.html ↩︎

In an interview conducted by Carlos Hernández with Pedro Nolasco Díaz Carabalí, the interviewee stated he had been born in 1908 but that his papers had been burned, and when these were issued again they changed the birth year to 1918 as it shows in the baptismal certificate (please, see illustration 6). Furthermore, in the 1939 deed, Pedro Nolasco appears as one of the minors, but if he was born on January 31, 1918, as found in the baptismal certificate, by the date the deed was signed, he must have been 21 years old, which by then was the legal age acknowledged per Act 27 of 1977 of the Colombian Congress. ↩︎