Abstract

The dispossession of Indigenous homelands disrupts communities’ social and political cohesion, cultural practices, and future security. The early twenty-first century has seen a rise in the global Indigenous rights movement, leading to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007) and a growing awareness of Indigenous issues. Central to this movement is the “land back” initiative, which includes government land claims hearings, the recognition of existing reservations, land returns, and financial reparations. Indigenous communities are pursuing self-driven models to reclaim their homelands. Voluntary financial reparations, or honor taxes, allow non-Native individuals and businesses to financially contribute to Indigenous welfare. The Nevada City Rancheria Nisenan Tribe (NCRNT) exemplifies this through their Ancestral Homelands Reciprocity Program (AHRP), which launched in 2018. The AHRP collects donations from residents and businesses to support the Tribe’s nonprofit, the California Heritage: Indigenous Research Project (CHIRP). The AHRP provides essential, unrestricted funding for the Tribe, addressing urgent needs like healthcare, transportation, and support for cultural initiatives. Grounded in the concept of “reciprocity,” the AHRP fosters stronger relationships and public awareness of historical injustices. This model secures financial support and builds mutual respect and engagement with neighboring communities, serving as a powerful example for other unacknowledged tribes and for the global Indigenous rights movement.

The dispossession of Indigenous homelands undermines communities’ ability to maintain social and political cohesion, sustain cultural practices, and imagine a secure future. The first quarter of the twenty-first century has witnessed the rise of a global Indigenous rights movement, which has led to the adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007), increased awareness of the discrimination against and dispossession of Indigenous groups, and amplified calls for self-determination regarding cultural, social, economic, and political rights.1 A core element of this movement has been the concept of “land back,” or the return of Indigenous homelands to their rightful stewards, in some form or another. This has materialized in four primary ways: (1) stronger recognition of reservations or ejidos previously set aside for Indigenous communities by treaty or government policy; (2) government-sponsored land claims hearings to adjudicate land compensation for Indigenous communities, which may or may not include land rights; (3) the return of land to Indigenous communities; and (4) mandatory or voluntary financial reparations. Indigenous groups across the Americas have advanced variations of these four forms of reparation in their specific political contexts.

Especially in the absence of strong governmental support or acknowledgement, Indigenous communities are exploring alternative models to pursue “land back” themselves. Voluntary financial reparations are one attractive model because the ability to advocate for such reparations resides with the Indigenous community. While monetary compensation is not necessarily equal to the land restitution, it does provide funding for social and cultural programs, economic development, and land acquisition. These voluntary land taxes, or honor taxes, are a mechanism by which non-Native individuals and businesses can contribute funding to Tribes directly or to other organizations promoting Indigenous welfare. Voluntary land taxes recognize the ongoing harm that Indigenous communities experience as a result of land dispossession and serve as a form of reparation. This approach has gained traction primarily in the United States, where nonprofit organizations can manage voluntary land taxes as a form of donation.2 The Nevada City Rancheria Nisenan Tribe (NCRNT) has developed a robust program called the Ancestral Homelands Reciprocity Program (AHRP).

The NCRNT is a federally unacknowledged Native American tribe in Nevada City, California. Prior to the California Gold Rush of 1849, Nisenan-speaking Indigenous communities inhabited the region bordered by the Sacramento River to the west and the Consumnes River to the south. Their territory stretched east to the crest of the Sierra Nevada mountains, and northwards to the north fork of the ‘Uba (Yuba) River, encompassing the region of present-day Nevada City. In 1891, the NCRNT secured its first legal title to land through the grant of approximately 75 acres of land to a tribal member, which was held in trust by the U.S. Government. In 1913, President Woodrow Wilson signed an executive order designating the same plot of allotment land as a reservation for the “Nevada or Colony Tribe of Indians.” Despite the Tribe’s relative success in maintaining an ancestral land base, the NCRNT was named in the 1958 California Rancheria Act, which led to the termination of their federal recognition in 1964. Today, the NCRNT is one of several California tribes whose federal status was revoked, resulting in the sale of their land and loss of federal services. Like most unacknowledged tribes, the lack of recognition deprives the NCRNT of their right to freedom of religious practice, the repatriation of stolen cultural artifacts, and access to federal health, housing, education, and job assistance programs. Furthermore, the lack of acknowledgement means that NCRNT members are frequently excluded from consultations and decision-making processes involving their ancestral lands and resources.3

The NCRNT face major challenges to their survival as a community as a result of their Tribe’s termination and the sale of their reservation land. In 2014, the NCRNT established the California Heritage: Indigenous Research Project (CHIRP), a nonprofit initiative overseen by the Nevada City Rancheria Tribal Council. The goal of CHIRP is to “research, document and preserve the history and culture of the Nevada City Rancheria Nisenan Tribe.”4 Since its inception, the scope of CHIRP’s mission has expanded such that CHIRP “creatively mimics” federal programs to “support the preservation, protection and perpetuation of the Nisenan people and their culture into the future, while advocating for the restoration of the Nevada City Rancheria’s federal recognition.”5 The question of how to fund these efforts, however, looms large.

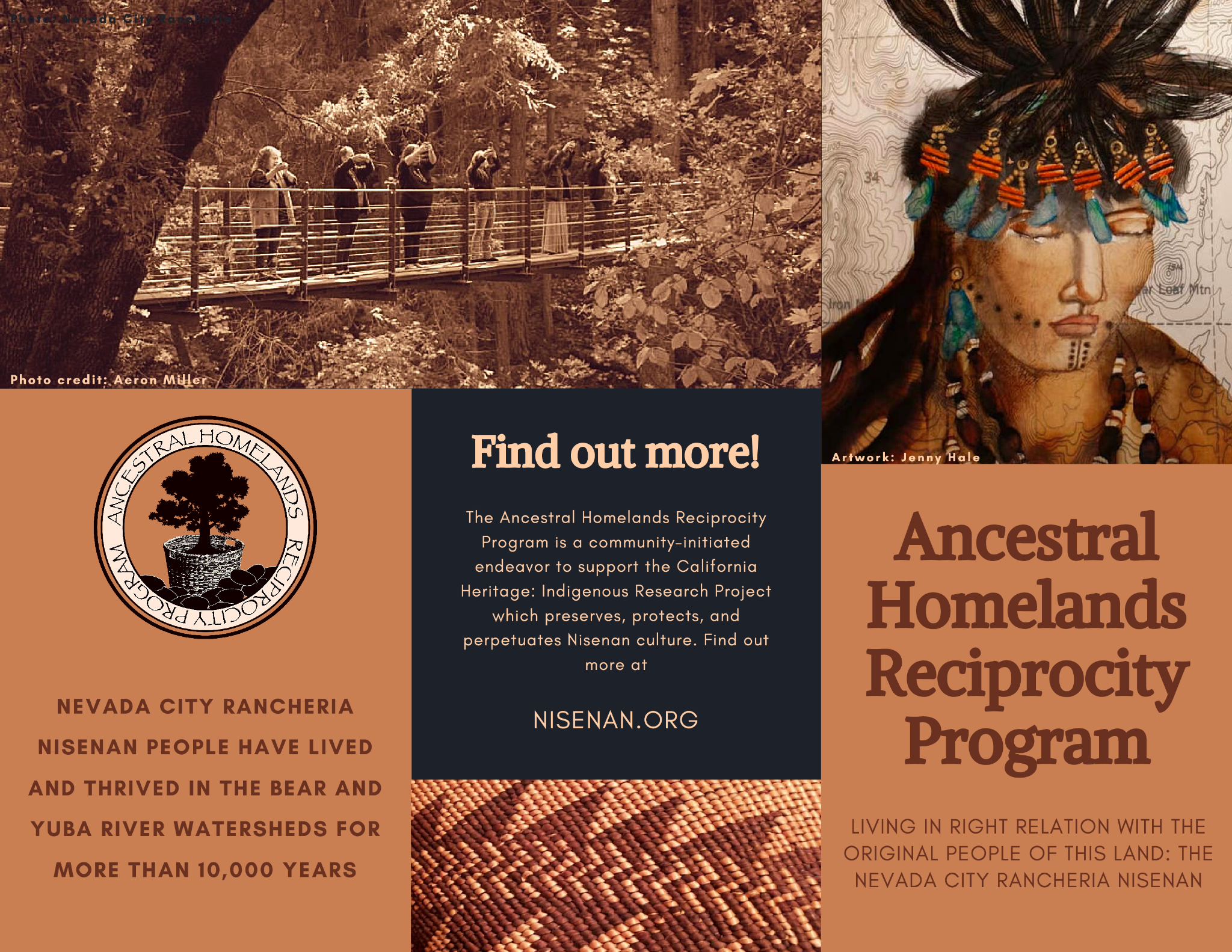

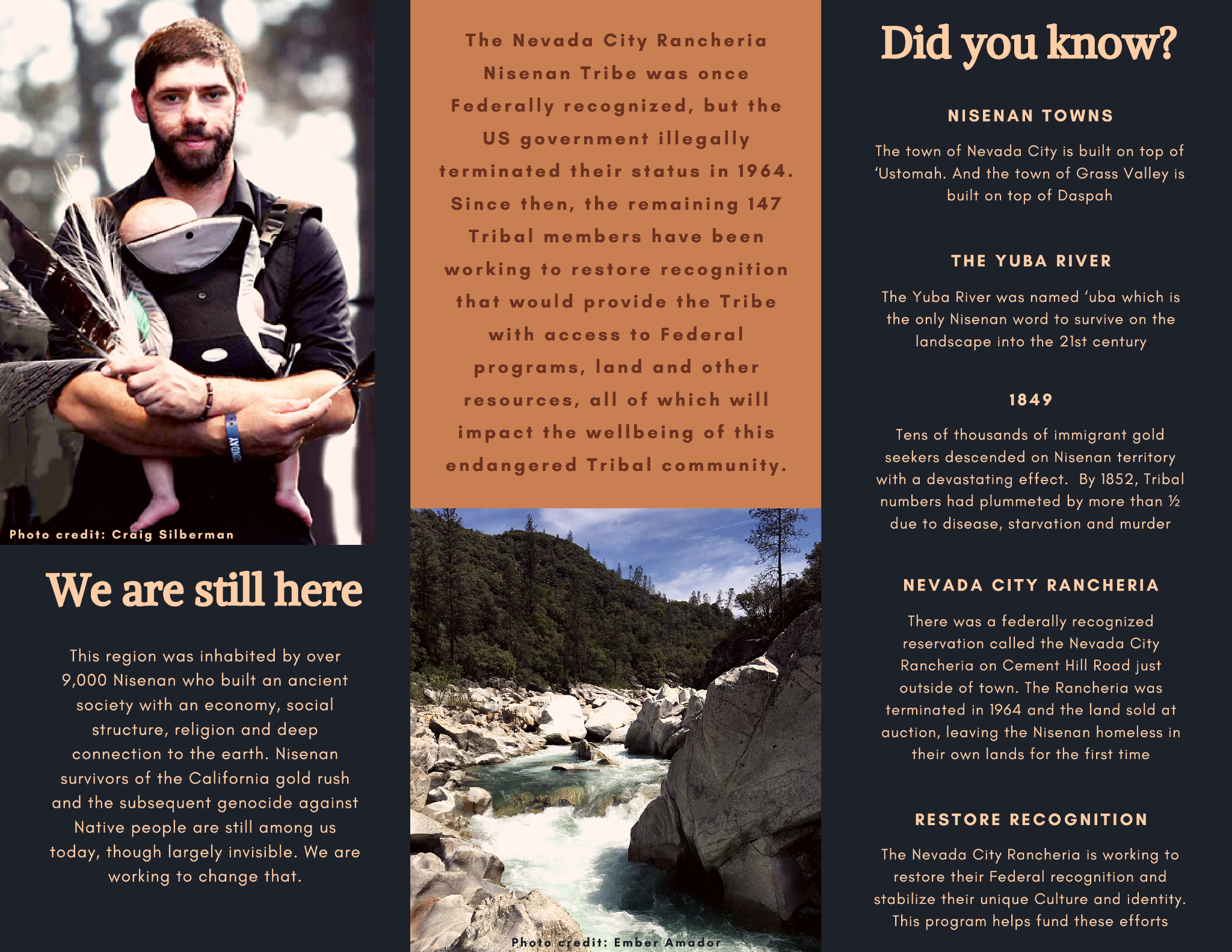

Ancestral Homelands Reciprocity Program brochure. More information available at NISENAN.ORG. Courtesy of the Nevada City Rancheria Nisenan Tribe. Artwork by Jenny Hale; Photography by Nevada City Rancheria, Aeron Miller, Craig Silberman, and Ember Amador.

In the context of the NCRNT’s dispossession, the creation of their Ancestral Homelands Reciprocity Program (AHRP) has proven to be novel and highly effective avenue for regaining rights and resources within their traditional homelands. Since 2018, the AHRP, which is a community-driven initiative modeled after reparations programs, has enabled the Tribe to rebuild many of the political and cultural institutions lost through dispossession. For this reason, the AHRP is a vital source of ongoing, unrestricted funding. The AHRP asks residents and businesses within NCRNT’s ancestral territory to make financial contributions to CHIRP in monthly, annual, and sometimes one-off installments. The AHRP recommends that contributors calculate their donations as a percentage of monthly or annual income, a flat or fixed monthly or annual contribution, a percentage of sales of a product, or a percentage of the annual value of a property.6 If its current trajectory is any indication, the AHRP could become a sustainable framework of significant material benefit for the NCRNT. When CHIRP began the honor tax program in 2018, they ended the fiscal year with $2,726, gifted to the program by seven individual donors and three businesses. Five years later, in 2023, the AHRP brought in a total of $132,008 from 260 individual donors and 60 businesses.7

The AHRP has been a source of significant material benefit for the NCRNT. Firstly, AHRP funds have been used to directly finance the urgent needs of Tribal members, the majority of whom live below the poverty line in Nevada County.8 This includes covering costs such as insurance and registration for cars, thus enabling Tribal members to maintain access to transportation. The AHRP has also funded direct health costs, as many Tribal members are excluded from federal health services and cannot afford private insurance. Beyond direct support to Tribal members, the AHRP has also directly supported the revival of language and cultural programs, including paying CHIRP staff who manage associated projects and covering the costs of project activities. The broad-ranging support deployed through the AHRP ultimately facilitates the agency and autonomy of the NCRNT in managing Tribal affairs and restoring the Tribe outside of formal governmental mechanisms. By employing an ongoing source of unrestricted funding, the Tribe can run and manage programs according to its needs and outside of the purview of donor demands and western donor frameworks.

Grounded in the NCRNT’s concept of “Reciprocity,” the AHRP has also become a key source of visibility and legitimacy-building for the Tribe within the local community. From a Tribal perspective, reciprocity refers to mutual exchange and interconnectedness among individuals, communities, and the environment. The NCRNT states that “Reciprocity is based on the mindset that we have a responsibility to our communities and to the Land, and that our Collective Liberation is reliant on our ability to support those less resourced than ourselves. By integrating Reciprocity into our daily practice, we move closer to living in Right Relationship with ourselves, with our communities, and with the Earth.”9 This approach has led to closer community relationships and networks that have then facilitated the Tribe’s ability to enter social and political spaces with deeper influence in the absence of formal acknowledgement by the U.S. Government.10

Specifically, by building mutual respect and engagement with non-Native residents, the AHRP encourages the public to “deepen their understanding” and acknowledgement of the historic and ongoing injustices affecting Indigenous peoples in Nevada County and California more broadly.11 By engaging in a reparations program, non-Native community members therefore become active participants in historical reconciliation and restorative justice efforts. This approach prioritizes the repair of social connections and enhances communication between the Tribe and the local community in Nevada County. The success of this approach is directly related to CHIRP’s framing of donations as a suggestion rather than a demand. This framing reflects the Tribe’s approach of authentic engagement and collaboration with the non-Native community to build a future based on shared respect and an awareness of the historical events that shaped the Tribe’s dispossession in Nevada County.

The AHRP serves as a model for voluntary land tax and reparations programs. In addition to providing a funding source to support the Tribe’s financial, social, and cultural needs, the AHRP goes further and promotes reciprocity, stronger relationships with non-Native residents, and greater public awareness of historical injustices. By framing donations as voluntary and respectful, the NCRNT has cultivated a supportive network that benefits both the Tribe and the broader non-Native community in the Nevada City area. The NCRNT’s approach to funding and community engagement is thus a powerful example for other unacknowledged tribes and the global Indigenous rights movement. The Tribe’s strategic nonprofit initiatives and emphasis on reciprocal relationships demonstrate that Indigenous communities can navigate the challenges created by historic dispossession and work toward restored recognition and autonomy.

References

Amador, Ember, Executive Assistant to the California Heritage: Indigenous Research Project. Voice message to author. May 26, 2024.

“Ancestral Homelands.” California Heritage: Indigenous Research Project. Accessed May 27, 2024. https://chirpca.org/ancestral-homelands.

“California Heritage: Indigenous Research Project.” California Heritage: Indigenous Research Project. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://chirpca.org/.

Campos, Diana, and Megan Renoir, “Indigenous Rights and Effective Climate Resilience: A Case Study of the Federally ‘Terminated’ Nevada City Rancheria Nisenan Tribe and Effective Management of Climate Vulnerabilities in Northern California, USA,” CDA Collaborative Learning Projects, July 2023.

Johnson, Richard B. History of Us: Nisenan Tribe of the Nevada City Rancheria. Santa Rosa, CA: Comstock Bonanza Press, 2018.

Niezen, Ronald. The Origins of Indigenism: Human Rights and the Politics of Identity. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2003.

Renoir, Megan, and Shelly Covert. “Recognition as Resilience: How an Unrecognized Indigenous Nation Is Using Visibility as a Pathway Towards Restorative Justice.” American Historical Review, Special Issue on Histories of Resilience, 2024.

Schueller, Brooke, and Avery White. “The California Tribe the Government Tried to Erase in the 60s.” Vice, January 17, 2018. https://www.vice.com/en/article/vbyxnx/the-california-tribe-the-government-tried-to-erase-in-the-60s-456.

“Voluntary Land Taxes.” Native Land Governance Center. March 9, 2021. https://nativegov.org/news/voluntary-land-taxes/.

For background on the global Indigenous rights movement, see Ronald Niezen, The Origins of Indigenism: Human Rights and the Politics of Identity (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2003). ↩︎

See “Voluntary Land Taxes,” Native Land Governance Center, March 9, 2021, https://nativegov.org/news/voluntary-land-taxes/. ↩︎

For background on NCRNT, see Richard B. Johnson, History of Us: Nisenan Tribe of the Nevada City Rancheria (Santa Rosa, CA: Comstock Bonanza Press, 2018). ↩︎

“California Heritage: Indigenous Research Project,” California Heritage: Indigenous Research Project, accessed June 1, 2023, https://chirpca.org/. ↩︎

“California Heritage: Indigenous Research Project.” ↩︎

“Ancestral Homelands,” California Heritage: Indigenous Research Project, accessed May 27, 2024, https://chirpca.org/ancestral-homelands. ↩︎

Ember Amador, Executive Assistant to the California Heritage: Indigenous Research Project, voice message to author, May 26, 2024. ↩︎

Brooke Schueller and Avery White, “The California Tribe the Government Tried to Erase in the 60s,” Vice, January 17, 2018, https://www.vice.com/en/article/vbyxnx/the-california-tribe-the-government-tried-to-erase-in-the-60s-456. ↩︎

“Ancestral Homelands.” ↩︎

Megan Renoir and Shelly Covert, “Recognition as Resilience: How an Unrecognized Indigenous Nation Is Using Visibility as a Pathway Towards Restorative Justice,” American Historical Review, Special Issue on Histories of Resilience, 2024. ↩︎

Diana Campos and Megan Renoir, “Indigenous Rights and Effective Climate Resilience: A Case Study of the Federally ‘Terminated’ Nevada City Rancheria Nisenan Tribe and Effective Management of Climate Vulnerabilities in Northern California, USA,” CDA Collaborative Learning Projects, July 2023, https://www.cdacollaborative.org/publication/indigenous-rights-and-effective-climate-resilience/. ↩︎