Abstract

Many Native American and Native Alaskan tribes in the United States remain unacknowledged, in part, due to historical dispossession. Only federally acknowledged tribes are eligible for specific rights and services, making federal acknowledgment crucial for the full realization of Indigenous rights in the United States. Tribes have gained acknowledgment through various legal mechanisms, including treaties, executive orders, congressional acts, and judicial decisions. The process, established in 1979 and revised in 1994 and 2015, is often criticized for being slow, arbitrary, and costly. Petitioning tribes must meet seven criteria, demonstrating continuous identification, distinct community, political authority, a current governing document, descent from a historical tribe, no dual enrollment, and no congressional prohibition. These criteria present significant challenges, particularly in providing documentary evidence. The administrative process is seen as a barrier, with high costs and long durations discouraging many tribes. Despite these obstacles, federal acknowledgment remains essential for tribes to secure their rights and recognition, prevent historical erasure and ensure their survival and identity are officially recognized.

As of 2023, the United States of America “acknowledges” the existence of 574 Native American and Native Alaskan tribes in the country. However, many more tribes exist but are not federally acknowledged, often due to circumstances linked to the historic dispossession of their homelands. In the United States, only federally recognized tribes are eligible for specific benefits known as Indian services, which are provided by the U.S. government through agencies like the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Indian Health Service. These services include access to healthcare, education, housing assistance, and economic development programs designed to support Native communities. Federally recognized tribes also have the right to repatriate ancestors and sacred objects under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, and their members are permitted to possess eagle feathers for religious ceremonies. Because federal recognition is a prerequisite for these and other legal rights, acknowledgment is critical for the full realization of Indigenous rights in the United States.

Native American tribes have gained acknowledgment through a variety of legal mechanisms. Historically, the cornerstone of U.S. Indian policy has been treaty relations with tribes. However, not all tribes received acknowledgment through treaties. In 1871, the U.S. Congress formally ended treaty-making, declaring that “no Indian nation or tribe . . . shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty.”1 Since then, other executive, congressional, and judicial authorities have acknowledged tribal existence. For instance, the President of the United States has acknowledged tribes by Executive Order, and the U.S. Congress has recognized tribes through legislation, such as the Mission Indian Relief Act in 1891 and the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934. Other forms of acknowledgment have come through the Bureau of Indian Affairs treating a tribe as having collective rights to lands or funds. These funds often come from resources like oil, gas, or timber on tribal lands, treaty payments, or settlements awarded to tribes as compensation for land that was wrongfully taken. Courts have also extended acknowledgment to tribes in certain cases, particularly when restoring tribes that had been terminated by congressional acts.

In 1994, the U.S. Congress passed legislation requiring the Bureau of Indian Affairs to publish an annual list of acknowledged tribes.2 In doing so, the U.S. Congress codified what had been an established practice and found that Native American tribes could be acknowledged by U.S. law, court decisions, or through administrative action under the Code of Federal Regulations for the “Federal Acknowledgment of American Indian Tribes.”3 In 2015, the Bureau of Indian Affairs made clear its preference for administrative action, and the Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs published policy guidance that it would refer all tribes seeking acknowledgment to the administrative process.4

The administrative process for acknowledgment, originally instituted in 1979 and revised in 1994 and 2015, is often criticized for being slow, capricious, and costly. Cases can take decades to resolve, and if a petition fails, there is no provision for submitting a new petition if additional evidence becomes available. Some tribes have received a positive preliminary finding in favor of acknowledgment only to have it reversed following a change in administration.5 The most significant obstacle, however, remains the cost of completing the required documentation. In 2021, the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Office of Federal Acknowledgment estimated the annual cost of preparing a petition for acknowledgment at $2,100,000.6 A lack of funds, missing documents, a reasonable fear of a failure (with 65% of all petitions denied since 1979), and arbitrary decisions all discourage tribes from moving forward through the administrative petition process.7

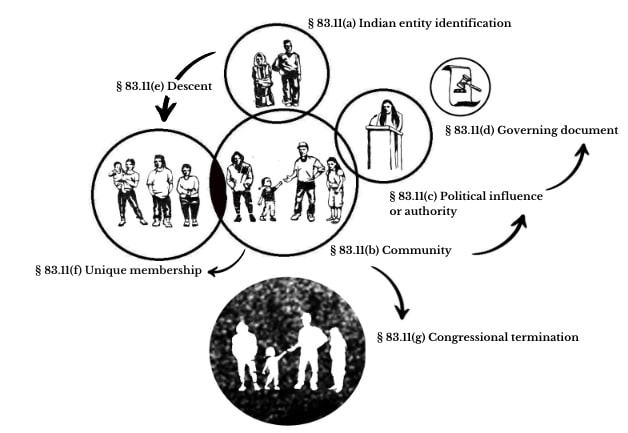

Seven criteria must be satisfied for federal acknowledgment as an Indian tribe. A petitioning tribe must demonstrate that: (1) they have been identified as an American Indian entity on a substantially continuous basis since 1900; (2) they are a distinct community that has existed since 1900; (3) they have exercised political authority over their members since 1900; (4) they have a current governing document that outlines their system of governance; (5) they descend from an identifiable historical Indian tribe; (6) their members are not enrolled members of other Indian tribes; and (7) their tribal existence has not been explicitly forbidden by the U.S. Congress. Each of these criteria presents unique challenges for petitioning Native American tribes, and the burden of proof remains on the tribe.

First, the “identification” criterion requires that petitioning tribes demonstrate recognition of their political existence from federal, state, and local governments, as well as from other tribes, tribal organizations, and academics. Often, however, a tribe’s political structures get overlooked when talking about culture and language. While anthropologists, archaeologists, and linguists often recognize that the people with whom they work belong to a cultural group, they are not always able to identify the political structures governing these communities. The Kumeyaay, for example, have thirteen distinct political governments on different reservations in California. Typically, agreements or relations with federal, state, and local governments provide stronger evidence for identification as an Indian tribe. Curiously, until 2015, petitioning tribes were not permitted to submit internal tribal records as evidence to prove their existence. Meeting minutes, bank records, and legal incorporation documents could therefore not be used to demonstrate that a tribe existed as a distinct entity. Nevertheless, despite these challenges, the identification criterion is generally considered one of the easier requirements for tribes to meet.

Second, the “distinct community” criterion requires a tribe to demonstrate that it is unique in some way from the surrounding population. The Bureau of Indian Affairs considers strong evidence to include distinct cultural and other ceremonial practices, language, and intratribal marriage—especially when more than 50% of the petitioning group can be shown to participate in these activities. However, decades of forced assimilation and government efforts to terminate tribes often make it difficult for tribes to meet this threshold. In such cases, a petitioning tribe may fulfill the distinct community criterion in other ways, including by demonstrating that its community maintains significant social relationships, patterns of informal social action, or shared or cooperative labor among its members. A common challenge tribes face is identifying documentary evidence that can point to distinct social relationships, transient but regular social interactions, or ephemeral shared activities. In the absence of written documentation, tribes turn to oral histories and other accounts. Relying on these memories is helpful and necessary, given the passing of tribal elders. Nevertheless, there are significant gaps in both oral and written records from the 1950s to the 1970s, which coincide with efforts to “terminate” the U.S. Government’s relationship with tribes. Petitioning tribes routinely face difficulty in demonstrating communal existence during the thirty-year period required under the distinct community criterion.

Third, the “political authority” criterion requires tribes to demonstrate that they have maintained political authority over their members from 1900 to the time of the petition. This criterion is particularly challenging because of the many changes that tribes have undergone since 1900, both as a result of their natural social evolution and in response to policies imposed upon them by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Moreover, this period witnessed the imposition of termination policies by the U.S. Congress and alterations to nonprofit and corporate organization under U.S. law. Under these historical circumstances, demonstrating political continuity in leadership becomes daunting. Successful petitions for acknowledgment, such as the petition by the Pamunkey Indian Tribe in 2016, have relied heavily on the continuity of governance over property granted to the tribe under British law prior to the establishment of the United States in 1789. However, most tribes do not have such clear historical records. Instead, they look to provide evidence of efforts to exert influence on the behavior of individual members or instances of undisputed community leadership. Nevertheless, finding strong documentary evidence of political authority remains a challenge for tribal communities, especially where informal leadership and deference to elders’ knowledge and experience has gone unrecorded.

Fourth, a petitioning tribe must demonstrate that it has a current governing document. Under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, participating tribes are required to vote on a tribal constitution, which must then be approved the U.S. Secretary of the Interior. The current administrative process for acknowledgment continues this approach, requiring tribes to submit the document they use for self-governance. This criterion is the simplest for all tribes to meet. While some tribes have had their petitions for acknowledgment denied, in part, due to not submitting a governing document, most unacknowledged tribes do have such documents in place and actively follow them.

Fifth, a petitioning tribe must demonstrate that its members descend from a historical tribe. Unlike the other criteria, which require a tribe to provide evidence postdating 1900, this criterion involves showing that the tribe’s members trace their ancestry to a tribe appearing on one of the tribal membership rolls (or lists) created the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In the absence of such a “base roll,” a petitioning tribe must reconstruct one using other records, such as those from federal, state, religious, or anthropological sources. While these records can serve as evidence for a reconstructed roll, they cannot be treated as a base roll on their own. This criterion has been a source of considerable controversy because, although the Bureau of Indian Affairs often recorded Native Americans and their tribal affiliations, not all tribes appear on official Bureau of Indian Affairs rolls. As a result, petitioning tribes often have to piece together fragmentary evidence from various sources to reconstruct a roll and prove their lineage. For Native Americans whose ancestors were subjected to Spanish colonization, the Bureau of Indian Affairs has asked for evidence of descent from tribes affiliated with the Spanish mission system.

Sixth, a petitioning tribe must demonstrate that its members are not already enrolled in another federally recognized tribe, as dual enrollment is not permitted. In practice, however, Native Americans often intermarry across both acknowledged and unacknowledged tribes. This can lead to situations where some individuals may feel culturally linked or bound by familial ties to an unacknowledged tribe but choose to enroll in an acknowledged tribe to receive federal benefits. These incentives generate tensions within unrecognized tribes, as those families with the strongest cultural or familial ties may not be able to enroll or participate in tribal governance if they are enrolled elsewhere. As a result, many unacknowledged tribes encourage their most active tribal members to delay enrolling in acknowledged tribes in the hopes that they might gain federal acknowledgment in the future.

Finally, a tribe must demonstrate that a federal relationship with it has not been explicitly forbidden by Congress. In the 1950s, a national policy known as “termination” sought to dismantle tribes and their reservations. Under this policy, reservations were divided among tribal members and privatized, effectively ending the unique federal relationship that had existed between tribes and the U.S. Government. Many tribes were targeted for termination, and the U.S. Congress enacted special legislation to dissolve their legal status. Although the federal government had officially rejected termination policy by the late 1960s, special legislation was still in place in states like California and Oregon, among others. While some of these laws have since been repealed and Indian policy has firmly shifted away from termination, the Bureau of Indian Affairs continues to interpret certain termination laws—often ambiguously worded and unevenly applied—as barriers to tribal acknowledgment, making this criterion open for considerable interpretation.

With these challenges embedded into the criteria for acknowledgment, the administrative process is often accused of being a form of “paper genocide.” Tribes that have maintained strong archival practices for creating and storing tribal records, despite all odds against them, have it a little “easier” in the acknowledgment process. For most tribes, however, the very first step in the acknowledgment process involves the creation of a tribal archive—searching for and assembling the records of tribal leaders and elders, finding the records of meetings (to the extent that they took place and were recorded), and locating any scrap of surviving evidence within the community that might serve as evidence for fulfilling acknowledgment criteria.

Without the proper documentation, a tribe can seemingly cease to exist in the eyes of the U.S. Government. Despite the obstacles, tribes continue to seek federal acknowledgment because this recognition is vital to being understood as a “real” tribe in the United States. The time and effort required mean that the struggle for recognition is multigenerational. The pain is very real when a tribal elder passes away and the tribe remains unacknowledged. Their children and grandchildren must often pick up the effort. For many tribes, acknowledgment is the pathway to preventing historical erasure.

References

“25 CFR Part 83 - Procedures for Federal Acknowledgment of Indian Tribes.” eCFR. Accessed May 28, 2024. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-25/chapter-I/subchapter-F/part-83.

“25 U.S. Code § 71 - Future Treaties with Indian Tribes.” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School. Accessed May 28, 2024. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/25/71#:~:text=No%20Indian%20nation%20or%20tribe,prior%20to%20March%203%2C%201871%2C.

“25 U.S. Code § 5130 - Definitions.” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School. Accessed May 28, 2024. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/25/5130.

“Final Determination Against Federal Acknowledgment of the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana.” Federal Register. Last modified November 3, 2009. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2009/11/03/E9-26373/final-determination-against-federal-acknowledgment-of-the-little-shell-tribe-of-chippewa-indians-of.

“Notice of Final Rule: Procedures for Federal Acknowledgment of Indian Tribes.” Federal Register. May 6, 2020. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-05-06/pdf/2020-09100.pdf.

“Petitions Resolved: Denied.” Office of Federal Acknowledgment, Bureau of Indian Affairs. Accessed May 28, 2024. https://www.bia.gov/as-ia/ofa/petitions-resolved/denied.

Procedures for Federal Acknowledgment of Indian Tribes, 25 C.F.R § 83.11 (2015).

“Proposed Finding for Federal Acknowledgment of the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana.” Federal Register. Last modified July 21, 2000. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2000/07/21/00-18490/proposed-finding-for-federal-acknowledgment-of-the-little-shell-tribe-of-chippewa-indians-of-montana.

“Requests for Administrative Acknowledgment of Federal Indian Tribes.” Federal Register. Last modified July 1, 2015. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2015/07/01/2015-16194/requests-for-administrative-acknowledgment-of-federal-indian-tribes.

For Additional Reading:

Klopotek, Brian. Recognition Odysseys: Indigeneity, Race, and Federal Tribal Recognition Policy in Three Louisiana Indian Communities. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011.

Meyers, Mark D. “Federal Recognition of Indian Tribes in the United States.” Stanford Law and Policy Review 12, no. 2 (2000): 271–300.

Miller, Bruce G. Invisible Indigenes: The Politics of Nonrecognition. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2004.

Miller, Mark E. Forgotten Tribes: Unacknowledged Indians and the Federal Acknowledgment Process. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2004.

Acknowledgment Process. Image courtesy of Ophelia Jackson.

Image courtesy of Ophelia Jackson.

“25 U.S. Code § 71 - Future Treaties with Indian Tribes,” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, accessed May 28, 2024, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/25/71#:~:text=No%20Indian%20nation%20or%20tribe,prior%20to%20March%203%2C%201871%2C. ↩︎

“25 U.S. Code § 5130 - Definitions,” Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School, accessed May 28, 2024, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/25/5130. ↩︎

“25 CFR Part 83 - Procedures for Federal Acknowledgment of Indian Tribes,” eCFR, accessed May 28, 2024, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-25/chapter-I/subchapter-F/part-83; Procedures for Federal Acknowledgment of Indian Tribes, 25 C.F.R. § 83.11 (2015). ↩︎

“Requests for Administrative Acknowledgment of Federal Indian Tribes,” Federal Register, last modified July 1, 2015, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2015/07/01/2015-16194/requests-for-administrative-acknowledgment-of-federal-indian-tribes. ↩︎

“Proposed Finding for Federal Acknowledgment of the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana,” Federal Register, last modified July 21, 2000, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2000/07/21/00-18490/proposed-finding-for-federal-acknowledgment-of-the-little-shell-tribe-of-chippewa-indians-of-montana; “Final Determination Against Federal Acknowledgment of the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana,” Federal Register, last modified November 3, 2009, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2009/11/03/E9-26373/final-determination-against-federal-acknowledgment-of-the-little-shell-tribe-of-chippewa-indians-of. ↩︎

“Notice of Final Rule: Procedures for Federal Acknowledgment of Indian Tribes,” Federal Register, May 6, 2020, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-05-06/pdf/2020-09100.pdf. ↩︎

“Petitions Resolved: Denied,” Office of Federal Acknowledgment, Bureau of Indian Affairs, accessed May 28, 2024, https://www.bia.gov/as-ia/ofa/petitions-resolved/denied. ↩︎