Abstract

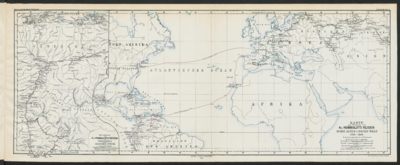

This map represents Guiana after the expedition of Walter Raleigh (1553-1618) between 1594 and 1595 and the publication of his memoir in 1596. Raleigh’s narrative acquired graphical representation in 1598 in this map crafted by the Dutch engraver Jodocus Hondius (1563-1612).

The publication of this map in Amsterdam was not fortuitous, as the Netherlands was highly interested in the Guiana’s region at the time.1 In the 16th century, the Spanish and the Portuguese had established in the densely populated areas of the Americas and delayed settling in Guiana. Three compelling reasons explain their delay and hesitancy. First, the fierce dominion of the Caribe people over the region and their vehement rejection of the colonizers. Second, the challenge of imposing a system of taxation and control over nomadic or semi-nomadic Indigenous groups. Third, the tropical forest’s uneasy conditions.

However, the Americas encountered a second wave of colonization in the late 16th century. British, Dutch, and French explorers sought to establish colonial settlements in “unclaimed” territories, such as Guiana. The ambition of possessing America’s richness fueled European empires. Walter Raleigh stands among those explorers. He received Queen Elizabeth’s authorization to conquer territories under her name in 1584. Besides commissioning explorations to North America in 1584 and 1587, he traveled and commanded two missions to the region of Guiana, in 1595 and 1617. Raleigh published the memoirs of his first trip in the Discovery of the Large, Rich, and Beautiful Empire of Guiana of 1596.2 In his book, Raleigh emphasized Guiana’s richness and stressed the assumed existence of the city of El Dorado.

Jodocus’ map broadly summarizes Raleigh’s narrative, locating it in the Guiana Shield. This geographical and geological region includes the current countries of Surinam, British Guiana, French Guiana, and parts of southeastern Venezuela, northern Brazil, and eastern Colombia. The map combines fictional and veritable data. On the one hand, aligned with Raleigh’s fixation with the myth of El Dorado, the map includes this fictional city by the shores of the also imagined Parime Lake, and it describes its purposed population’s customs, resources, and how to access them. The map presents legendary humans as headless men and a narrative about the Amazonas Kingdom.3

On the other hand, beyond this fantastic construction, the map mentions the human and natural conditions of the territory. In Raleigh’s narrative, the British explorer includes accounts of his encounters with locals and their reports about the location of other Indigenous communities, of which there is information nowadays.4 Archeological research confirms that people on the coast were mainly from Caribe and Arawak linguistic families, with nomadic and semi-nomadic groups from the Tupi-Guarani family in the interior. Moreover, the map also includes images of detailed American fauna, such as turtles by the Orinoco River or armadillos or the natural resources of Cayenne.5

The power of the Raleigh’s narrative and Hondius’ cartographic and pictorial representation of it will be long-lasting. For instance, the depiction of the mythic Parime Lake in maps of South America will remain commonplace for over two centuries, all the way to the 19th century.6 In fact, this map will be the reference from which most Europeans envisioned the land of Guiana and one of the earliest accounts of its population.7

Map citation:

Jodocus Hondius. Nieuwe Caerte van het wonderbaer ende goudrijcke landt Guiana, gelegen onder de Linie Aequinoctiael tusschen Brasilien ende Péru. Map, 36,5 x 52 cm. Amsterdam, 1598. Bibliothèque Nationale de France - Gallica. Accessed August 1, 2023. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b531217166

Marion F. Godfroy, Kourou and the Struggle for a French America (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 44. ↩︎

Walter Raleigh, Discoverie of The Large, Rich, And Bevvtifvl Empire of Gviana, With A Relation of The Great And Golden Citie Of Manoa (Which The Spanyards Call El Dorado) (London: Imprinted at London by Robert Robinson. 1596). In the digital collection *Early English Books Online Demo. *https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebodemo/arz7311.0001.001. University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. Accessed July 7, 2024. ↩︎

The description located under the Essequibo River reads: “The surrounding nations/groups of this river traveled in a few days from the mouth of the same river to a day’s journey to the Great Lake Parime. From there, they first brought the goods over their shoulders overland to the lake. After that, they travel with their canoes and carried their goods overland again to the Salt Lake to trade. Usually, the Spaniards do not adventure further than the Essequibo river.” (I thank the historian Miguel Durango for his help with this translation.) ↩︎

Pluchon and Abénon, Histoire Des Antilles Et De La Guyane, 36-37; Serge Mam-Lam-Fouck and Apollinaire Anakesa-Kululuka, Nouvelle Histoire De La Guyane Française: Des Souverainetés Amérindiennes Aux Mutations De La Société (Matoury, Guyane: Ibis rouge, 2013), 28. ↩︎

The second paragraph under the representation of the Oyapok River says: “Cajane is a very clean and suitable river to enter/come with many ships. At its beginning or mouth, it is more than a German mile wide. There are three rocks at the mouth, through which it also has three outflows. The nations around here are very rich in provisions and good at trading. It is believed, for sure, that by means of these rivers, one could access the great lake and the city of Manoa, which is very rich in wood/timber.” (I thank the historian Miguel Durango for his help with this translation.) ↩︎

See, for instance: CNT0010, CNT0018, CNT0061, CNT0062, CNT0063, CNT0066, CNY0074, VEN0052, VEN0056, VEN0058, VEN0068, VEN0099. ↩︎

Godfroy, Kourou, 41. ↩︎