Abstract

In North America, many historical sites of colonial encounters feature monuments that honor European colonial settler histories, while obscuring Indigenous histories. For example, in 1912, the Franco-American community in Plattsburgh, New York erected a dramatic monument to Samuel de Champlain, and positioned it on the western shore of Lake Champlain. The inscription identifies him as “Navigator, Discoverer, Colonizer,” and the sculpture includes a crouching Native American scout at his feet. Although meant to record the success of inter-cultural alliances in New France, this monument evokes memories of the violent, and ongoing, impacts of European colonization. Recent attempts to improve the monument by adding a new interpretive plaque made things worse, introducing confusing images that further obscure Indigenous histories. From a Native perspective, monuments to colonial encounters are rarely celebratory; they are often painful reminders of diplomacy gone wrong and colonization run rampant.

The Indigenous territory that we now call “North America” is covered with monuments to the colonial settler past that, in many cases, stand unquestioned, despite the historical errors and stereotypes they typically embody. In examining these markers, it is crucial to understand exactly why these monuments exist. What was the historical context: who is this person, when did they live, and why do they matter? What was the popular social context: when was the monument created, who designed it, why is it beloved? What was the ethnic and political context: which communities were being intentionally represented by this monument, and who was misrepresented or marginalized as a result? Perhaps the most important point to be made is that public images and words matter. The general public has been trained to believe, based on the Euro-American tradition of erecting statues to “important” people, that these monuments communicate some kind of elemental “truth.” There is, however, so much more to be said.

As a case in point, there is an impressive monument to French “Navigator, Explorer, Colonizer” Samuel de Champlain (1567-1635), standing proudly on the western shore of Lake Champlain in present-day Plattsburgh, New York, even though Champlain never set foot on that shore. [Figure 1.] The monument — which stands in Kanienkehaka (Mohawk) territory, overlooking the place the Abenaki call Bitawbakw (Lake Champlain) — was erected by members of the Franco-American community in Plattsburgh and dedicated in 1912. Related monuments and markers to Champlain were set up in various locales on the Vermont side of the lake in Swanton, Vergennes, and Isle La Motte. Champlain was especially popular during the tercentenary year of 1909, when Fort Ticonderoga and other locales hosted pageants and re-enactments celebrating the infamous “Battle of Lake Champlain” in 1609.1

Champlain is an unusual example of a European colonizer who was actually invited to these lands by Indigenous people. In 1609, a group of Maliseet, Montagnais, Algonquin, and Abenaki leaders asked him to serve as an ally in their conflict with the Haudenosaunee (then known to colonizers as the Five Nations Iroquois). Champlain’s first-person account of the July 30, 1609 “Battle of Lake Champlain” describes the ritual nature of Indigenous warfare, while also noting the shock at the unexpected havoc created by the first use of European firearms in this region.

“When evening came we embarked in our canoes to continue on our way; and as we were going along very quietly. . .we met the Iroquois at ten o’clock at night at the end of a cape that projects into the lake on the west side [near present-day Fort Ticonderoga]. We both began to make loud cries, each getting his arms ready. . . When they were armed and in array, they sent two canoes set apart from the others to learn from their enemies if they wanted to fight. They replied that they desired nothing else; but that, at the moment, there was not much light and that they must wait for the daylight to recognize each other, and that as soon as the sun rose they would open the battle. . .the whole night was passed in dances and songs, as much on one side as on the other, with endless insults and other talk. . . After plenty of singing, dancing, and parleying with one another, daylight came. My companions and I remained concealed, for fear that the enemy should see us, preparing our arms. . .After arming ourselves with light armor, each of us took each an arquebuse [a short musket] and went ashore. I saw the enemy come out of their barricade, nearly 200 men, strong and robust to look at, coming slowly toward us with a dignity and assurance that pleased me very much. At their head were three chiefs.” 2

Figure 2: “Champlain’s Fight with the Iroquois,” illustration by Samuel de Champlain c. 1613, in Francis Parkman, Historic Handbook of the Northern Tour. Lakes George and Champlain; Niagara; Montreal; Quebec (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company, 1912), 9.

“They at once saw me and halted, looking at me, and I at them. When I saw them making a move to shoot at us, I rested my arquebuse against my cheek and aimed directly at one of the three chiefs. With the same shot two of them fell to the ground, and one of their companions who was wounded and afterwards died. . .The Iroquois were much astonished that two men had been so quickly killed, although they were provided with [arrow-proof] armor. . .As I was loading again, one of my companions fired a shot from the woods, which astonished them again to such a degree that, seeing their chiefs dead, they lost courage, took to flight and abandoned the field and their fort, fleeing into the depths of the woods. Pursuing them thither I killed some more of them. . . After we had gained the victory they [Champlain’s Native allies] amused themselves by taking a great quantity of Indian corn and meal from their enemies, and also their arms, which they had left in order to run better.” 3

In the aftermath of this brief, but devastating encounter, Champlain’s allies “made good cheer, danced and sung,” and collected prisoners. In his journal, he noted that he then took the liberty of naming the lake “ where this charge was made” after himself: “Lake Champlain.”

The effects of this encounter were long-lasting, given the subsequent widespread use, of firearms in inter-national and inter-tribal warfare. The arrogance of naming the lake after himself is obvious, but Champlain was not (like so many colonizers) driven solely by the assumption that European colonizers had inherent rights to claim non-Christian lands under the “doctrine of discovery.” His goal - in line with the painful legacy of settler colonialism everywhere - was to colonize Indigenous lands with settlers from Europe to create the colony of “New France.” Thus, although meant to record the success of inter-cultural alliances in New France, this monument also evokes memories of the violent impacts of European colonization. Indigenous peoples suffered through generations of inter-cultural warfare, land loss, and religious oppression that their communities are still recovering from today. From a Native perspective, these monuments to colonial encounters are not celebratory; they are painful reminders of diplomacy gone wrong.

The Champlain monument still stands watch over the lake in the present day, with its stereotypical and culturally inaccurate portrayal of an eastern Algonkian Native warrior in a Western Plains style feather headdress (bearing no resemblance to Native dress in the 1600s), crouching at the foot of the pedestal. [Figure 3.]

Figure 3: Samuel Champlain monument, Plattsburgh, New York. Photograph by Margaret M. Bruchac.

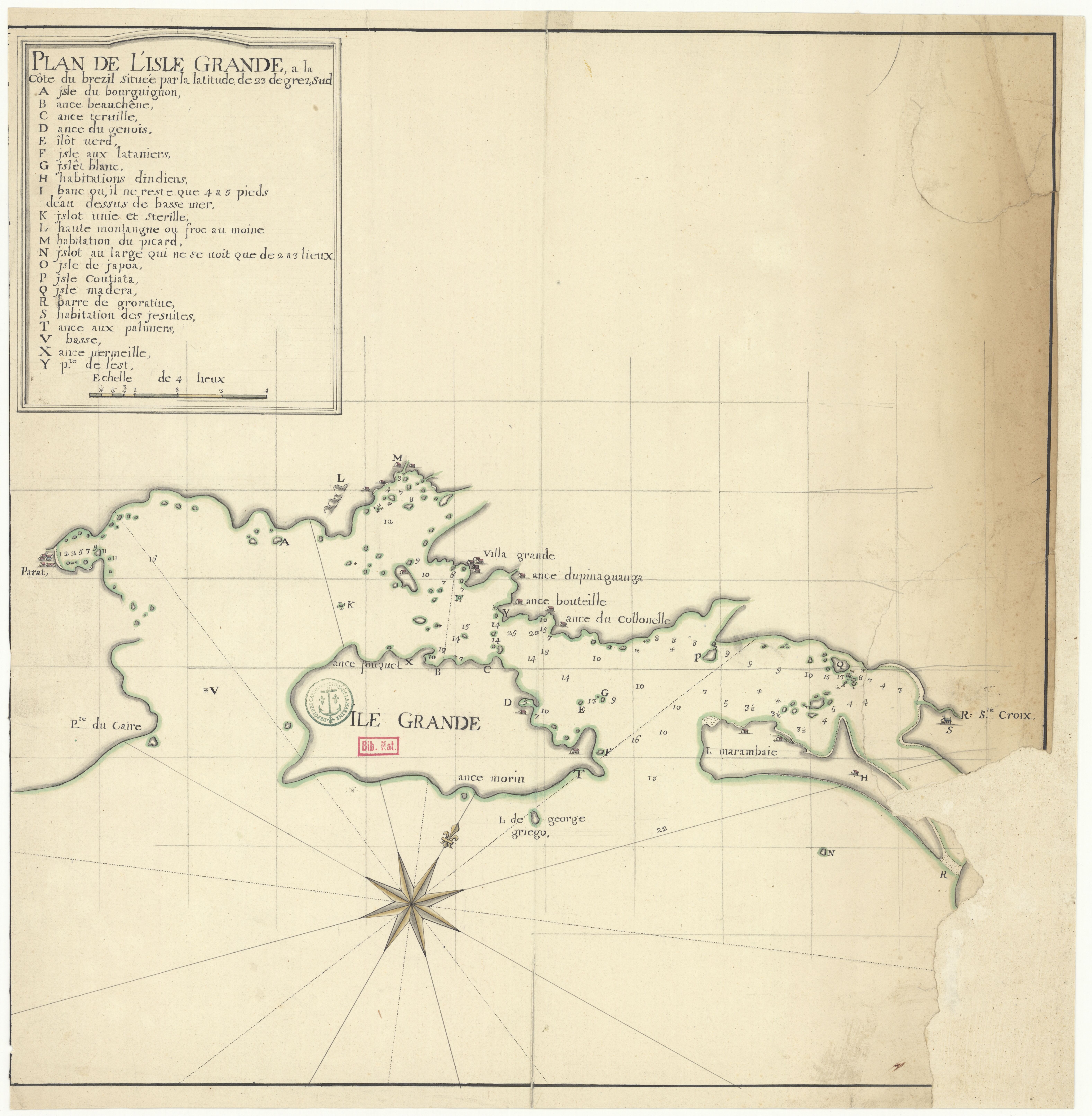

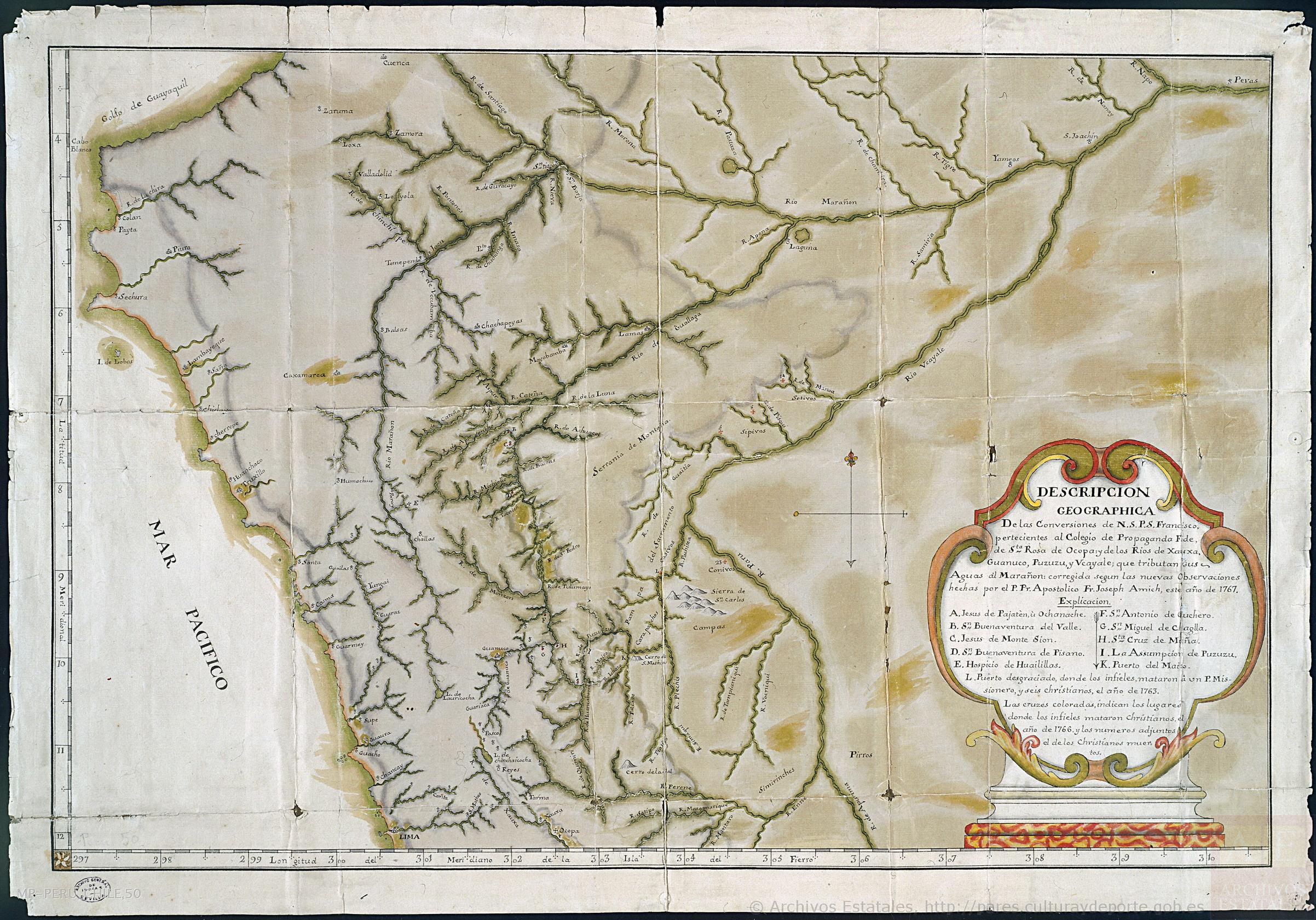

In 2020, in an effort to somehow reconcile with this fraught history and awkward imagery, the city of Plattsburgh decided to install a new interpretive plaque.4 This plaque represented an attempt to fill in the blanks by highlighting Indigenous history, but it introduced considerable confusion.5 Although intended to address historical errors, the design mixes accurate and inaccurate images and text in a curious manner.6 It features a very large (and very antiquated) map that includes illustrations of nearly naked Natives depicted in a typically Euro-centric romantic fashion. Champlain’s own illustration of the famous Battle at Lake Champlain is strikingly absent.

The plaque includes two modern illustrations by John Fadden, a skilled Haudenosaunee artist. One shows a Maliseet canoe, and one shows an Onondaga Chief addressing John Hancock in Philadelphia in 1776. Both of these are culturally accurate and interesting, but Hancock’s relations with Haudenosaunee people in the 1770s have no relation to Champlain’s relations with his Algonkian allies, or to his battle with the Iroquois in the 1600s. There is also an image of a new US dollar coin, with an image of Sacagawea, the Lemhi Shoshone woman who accompanied the 1804-1806 Lewis and Clark Expedition on the other side of the continent. There is no explanation for including this image, which has no relation whatsoever to any aspect of Lake Champlain’s history.

The plaque also features a new map of the lake itself, which unfortunately obscures any sense of the lake as part of long-inhabited Indigenous homelands and ancestral territory. There are no markers to show the past or present locations of any of the Indigenous communities – at Missisquoi, Kahnawake, Kanesatake, and Odanak – who are historically connected to this region and this lake. There is no mention of either Mohawk or Abenaki history, even though this monument stands at the edge of the lake that connects their territories. There is no mention of any Indigenous nations today, or of the complex inter-tribal relations among them. In essence, the plaque obscures, rather than illuminates, Indigenous history.

In the end, monuments like these to colonial heroes and colonial encounters — even when they purport to celebrate the transnational nature of early alliances — stand as painful reminders of diplomacy gone wrong and colonization. This statue, even with its new plaque, remains firmly rooted in the past. Clearly, more context, more information, and better interpretations of these foundational histories are needed.

References Cited:

Barilla, Elena. July 22, 2020. “‘Interpretive panel’ added to Samuel de Champlain monument in Plattsburgh.” NBC5 News. https://www.mynbc5.com/article/interpretive-panel-added-to-samuel-de-champlain-monument-in-plattsburgh/33383840.

Beaudreau, Sylvie M. July 24, 2020. “In My Opinion: The Friends of the Saranac River Trail and their interpretive panel for the Champlain Monument: Thoughtful or misleading?” The Press Republican. https://www.pressrepublican.com/opinion/in-my-opinion-the-friends-of-the-saranac-river-trail-and-their-interpretive-panel-for/article_d72c2b5c-5d6e-5341-94ac-611af7f20f49.html.

Beaudreau, Sylvie M. “Commemorating a Transnational Hero: The 1909 Celebration of the Tercentenary of the Discovery of Lake Champlain.” Vermont History 77, no. 2 (Summer/Fall 2009): 99–118. https://vermonthistory.org/journal/77/VHS770202_99-118.pdf.

Bradley, Pat. July 22, 2020. “Champlain Statue Remains With Education Panel Installed To Explain Historical Errors.” WAMC Northeast Public Radio. https://www.wamc.org/north-country-news/2020-07-22/champlain-statue-remains-with-education-panel-installed-to-explain-historical-errors.

Bourne, Edward Gaylord, ed. 1922. The Voyages and Explorations of Samuel de Champlain 1604–1616 Narrated by Himself. Translated from the original French by Annie Nettleton Bourne. New York, NY: Allerton Books. https://libsysdigi.library.uiuc.edu/oca/Books2008-05/voyagesexplorati/voyagesexplorati01cham/voyagesexplorati01cham.pdf.

Hill, Henry Wayland, ed. 1911. The Champlain Tercentenary Report. Report of the New York Lake Champlain Tercentenary Commission. Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Company.

Lake Champlain Tercentenary Commission of Vermont. The Tercentenary of the Discovery of Lake Champlain and Vermont: A Report to the General Assembly of the State of Vermont. Montpelier, VT: Capital City Press, 1910.

Parkman, Francis. 1912. Historic Handbook of the Northern Tour. Lakes George and Champlain; Niagara; Montreal; Quebec. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company. https://archive.org/details/cu31924014024305/page/n9/mode/2up

List of Figures:

See, for example, Henry Wayland Hill, ed., The Champlain Tercentenary Report (Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Company, 1911). ↩︎

Samuel de Champlain, quoted in Edward Gaylord Bourne, ed., The Voyages and Explorations of Samuel de Champlain 1604-1616, translated from the original French by Annie Nettleton Bourne (New York, NY: Allerton Books, 1922), Vol. 1, 209-211. ↩︎

Samuel de Champlain, quoted in Bourne, ed., The Voyages and Explorations of Samuel de Champlain 1604-1616, Vol. 1, 212-213. ↩︎

See Elena Barilla, “Interpretive panel’ added to Samuel de Champlain monument in Plattsburgh,” NBC5 News, July 22, 2020. https://www.mynbc5.com/article/interpretive-panel-added-to-samuel-de-champlain-monument-in-plattsburgh/33383840 ↩︎

The new plaque also, not incidentally, erases the legacy of the Franco-American descendant community that built the monument. See Sylvie M. Beaudreau, “In My Opinion: The Friends of the Saranac River Trail and their interpretive panel for the Champlain Monument: Thoughtful or misleading?” The Press Republican, July 24, 2020. ↩︎

See Pat Bradley, “Champlain Statue Remains With Education Panel Installed To Explain Historical Errors,” WAMC Northeast Public Radio, July 22, 2020. https://www.wamc.org/north-country-news/2020-07-22/champlain-statue-remainswith-education-panel-installed-to-explain-historical-errors ↩︎