Abstract

What is MALLKUANKA- Vuelo Surnorte De Colores/ The South-North Flight of Colors?

How do we imagine encounters of people from the south and the north? How do we foster connections between South America and North America, or Latin America and the U.S.? Renowned Bolivian and Aymara artist Roberto Mamani Mamani, with a team of people from Bolivia and Philadelphia, created and painted the vibrant mural MALLKUANKA – Vuelo Surnorte de Colores/The South-North Flight of Colors in Philadelphia, PA, as a way of visualizing unity. The mural’s beauty highlights the interrelationships of people and nature in ways that transcend borders.

MallkuAnka depicts Andean and Philadelphia landscapes, using color to chart encounters among cultures and beings. The mural harmonizes dualities that emerge from meetings: the condor (south) and the eagle (north), the city and the mountains, the sun and the moon, the earthly and the sacred. Painted on the side of a veterinary clinic (PASE), along a long wall (130’ wide/ 20’ high), animals representing South and North America bring together both cultures under the embrace of Pachamama, or Mother Earth — the mural’s central figure. The design shows the importance of unity between two hemispheres, with the flight of the condor and eagle from south to north, and how people from both can live in harmony respecting the Pachamama, and all that she symbolizes, including energy and life.

In the creation of MALLKUANKA – Vuelo Sur-Norte de Colores/The South-North Flight of Colors, Mamani Mamani was assisted by Yody Ruben Quisbert Quispe, Ilampu Adhemar Aguilar Jove, Ilimani Gabriel Aquilar Jove, Emmanuel Amaru Aquilar Jove and Mara Henao.1

Who is Roberto Mamani Mamani?

Roberto Mamani Mamani is an internationally acclaimed Aymara artist and muralist from La Paz and Cochabamba, Bolivia. His extraordinary, vivid artwork depicts symbols of the Andean Indigenous tradition and cosmovision or worldview, conveying strength, pride, and a commitment to sustainable, peaceful, and spiritual living. He weaves in historical themes such as the impact of colonization and how the Aymara-Quechua community, after years of marginalization and oppression, has fought for an empowered collective identity in the region. A self-taught artist, Mamani Mamani has displayed his artwork in approximately 60 exhibitions worldwide, including in Argentina, Brazil, United States, Mexico, Italy, France, and the United Kingdom. He has participated in World Expos and the La Biennale Di Venezia/ International Art Exhibition in Italy, and he has received numerous national and international accolades over the years. In addition, Mamani Mamani painted giant, 12-story murals on the Wiphala community housing project in El Alto, Bolivia, a city adjacent to La Paz.

His art brings to life the spirit of “Buen Vivir” (or Sumak Kawsay in Quechua), a movement and philosophy inspired by the Andean cosmovision that calls for living in harmony with the community and environment, and rejecting rampant, unfettered consumerism and capitalism. At a very young age, Mamani Mamani began creating art in his hometown of Cochabamba, and throughout his career the principles of Buen Vivir and the entire Andean cosmovision have driven his work and artistic fervor. He greets everyone with “Jallalla: toda la energía de los Andes,” or may all of the energy of the Andes be with you.

Why commission this mural in Philadelphia?

The mural’s magnificent artwork was produced by Mamani Mamani as part of the Penn-Mellon Dispossessions in the Americas project, with organizational support from the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Latin American and Latinx Studies, the University of Pennsylvania’s Sachs Program for Arts Innovation, and Mural Arts Philadelphia.

Mural Arts Philadelphia is “dedicated to the belief that art ignites change.” The 50-100 public art projects led annually by Mural Arts are carried out through a participatory process, which aims to “to create art that transforms public spaces and individual lives.”

“Mural Arts Philadelphia envisions a world where all people have a say in the future of their lives and communities; where art and creative practice are respected as critical to sense of self and place; and where cultural vibrancy reflects and honors all human identities and experiences.”2

Mural Arts also emphasizes inquiry-based learning and respectful and mindful collaboration. Their programming spans restorative justice, arts education, and civic engagement.

This collaborative community-university project represents a relatively rare opportunity. In fact, in an interview with Mural Arts Executive Director Jane Golden, she mentioned that university partnerships with Mural Arts have been few, saying one can “count them on one hand.”3 The MallkuAnka initiative also provided an opportunity to invite an international artist to Philadelphia, which “aspires to be a global city”.4

The themes and images of the mural are relevant for communities across the world.png says Eduardo Gudyana, a senior researcher at the Latin American Center for Social Ecology.5 Philadelphia still holds the record for the highest poverty rate among the largest cities of the United States, with an average of 21.7% of people living in poverty, soaring to 33% for Hispanics and 35% for adults with less than a high school diploma, according to the Pew Foundation.6 The Andean cosmovision, with the “buen vivir” concept, is important for Philadelphia and other cities like it, worldwide, that confront poverty, racism, gun violence and other societal problems that threaten health, wellbeing and community.

The mural also highlights the importance of diversity in Philadelphia. Sixteen percent of the approximately 1.5 million people who live in Philadelphia identify as Latino or Hispanic.7 It is also important that the mural captures the importance of Indigenous peoples and their philosophies, because narratives about Indigenous peoples found in education, by leaders, or in mass media often propagate harmful and discriminatory stereotypes.8

Naeemah Patterson, one of the MallkuAnka mural project coordinators with Mural Arts Philadelphia, explained that MallkuAnka sends the message “we’re here,” including everyone who is Indigenous, Latin American, or who finds meaning in the Andean Cosmovision. “It’s a big, bright, obvious sign that we’re here, so children can see that and identify with that, and elders can see that and feel validated and welcome,” said Patterson.9

Delving deeper into the MallkuAnka mural and its symbols:

Condor and Eagle: According to Mamani Mamani, Mallku, or Aymara for condor, represents authority, and is a spiritual guide of the Andes. Anka is Quechua for eagle, North America’s regal bird. The mural’s subtitle refers to the flight from south to north, and the artist uses many different colors to recognize that we are all equal; that we can walk together, and the condor and eagle coming together represent this. The Pachamama shows happiness and sadness for her children and it reflects that all beings are alive - not just humans but also plants, animals, and other creatures.

The condor is on the left and the eagle on the right. Photo by Erin Blewett.

The wings attached to the condor (on the left side) sport the colors of the Wiphala, and the right side colors, connected to the eagle, reflect the colors of the U.S. flag. Laura González Tinoco, an art historian, who is a scholar of Mamani Mamani’s works, explains:

“The central figure of the mural represents the divinity Pachamama, surrounded by resplendent coca leaves, escorted by a double-headed bird with its wings outstretched. With this gesture, the painter expresses his good will and hopes for unity between the nations, by representing the head of the condor (South America) and the eagle (North America) fused to accompany Mother Earth. This vision corresponds to the embodiment of the popular prophecy that announces a time in which the two birds will come to meet them to accompany their flight, so that the two Americas will meet again in the mythical continent of Abya-yala.”10

Cosmovision and animals: Mamani Mamani explains that the mural captures a cosmovision in each space, which is the encounter between the Andes and Philadelphia. The animals painted on the Philadelphia side of the mural are endemic to North America, like squirrels, bison or buffalo, wolves, deer, and owls. On the other side, you have bears, llamas, quirquinchos, and vizcachas. The mural reflects the artist’s reverence for animals and nature, including the Andean mountain ranges (on the left side of the mural).

González Tinoco underscores that “the mural also tells us about the importance of animals in the spirituality of Indigenous peoples.” For example, she explains, “the bird refers to the tutelary visit of the spirits of the ancestors, while the llama is another sacred animal” with “prominence in rituality.”11

Images of animals on the Philadelphia side of the mural, including buffalo and squirrel. Photo by Erin Blewett.

A bison or buffalo, native to North America. Photo by Erin Blewett.

Bears, a mammal inhabiting both North and South America. Photo by Erin Blewett.

Beautiful birds, an armadillo or quirquincho and llamas, on the Andean side of the mural. Photo by Erin Blewett.

![An armadillo, originally from South America—although there are now many in the United States. In 2022, Bolivia declared the endangered armadillo or the quirquincho, as part of its natural heritage to increase conservation efforts.[^12] Photo by Erin Blewett.](/images/content/BartchC001/image7.jpeg)

An armadillo, originally from South America—although there are now many in the United States. In 2022, Bolivia declared the endangered armadillo or the quirquincho, as part of its natural heritage to increase conservation efforts.[^12] Photo by Erin Blewett.

Pachamama: The central feature of the mural is the Pachamama. Pacha means earth, cosmos, universe in Quechua and Aymara, and the second part of the word, mama, means mother. She is the Goddess of nature, fertility and crops. An offering to her is an offering to the spiritual world. It’s a term that has important meaning for Indigenous people in the Andes because they see themselves as interconnected with the spiritual and natural world; they are integrated into it. According to González Tinoco, the Pachamama represents time and space, and the importance of earth and the synthesis between humans and nature.

At least 60 percent of Bolivians trace their heritage to Indigenous peoples, and offerings to the Pachamama are commonplace. These can be in the form of flowers, or pourings of drink or coca leaves onto the ground. Bolivians who are Catholic also show respect and offerings to the Pachamama.

The Pachamama as depicted by Roberto Mamani Mamani. She is painted in the center of the mural, representing the powerful force of Mother Earth. Photo by Erin Blewett.

Wiphala: Known as the Andean flag, this is a squared representation of the rainbow which is considered sacred in ancient knowledge. In the present, the Wiphala also is a symbol of Indigenous pride. Many communities in the Andes reclaim the Wiphala as a representation of their culture. In the above photo, the female figure of the Chacha Warmi holds the Wiphala.

Nature: There are many elements in nature (sun, moon, thunder, etc.) that are considered part of the Pachamama. Therefore, nature cannot be reduced to commodities; it is sacred. Natural elements complement each other and have spiritual significance. This Andean cosmovision, based on respect for the earth, contributes greatly to contemporary global conversations on how to take care of the planet during times of climate change.

Coca: Coca is a sacred leaf, and it is used as an offering to Mother Earth. In fact, common offerings give coca to various levels of the spiritual world. Coca could be given as an offering for the underworld (Uju Pacha) represented by the powerful, wise serpent or Amaru; Kay Pacha (the surface world that we inhabit as humans (also known as Pacha Mama), symbolized by the mighty puma; or to Janaq Pacha (the upper world), symbolized by the soaring condor. Sometimes shamans – spiritual leaders- believe that coca leaves connect us with the gods of the three worlds.

In the mural, Roberto Mamani Mamani has painted coca leaves on both sides of the arc that adorn the Pachamama. On the left side, the arc is painted the colors of the Wiphala, and on the right side, the arc is painted the colors of the flag of the city of Philadelphia.

Coca leaves adorning the Pachamama. Photo by Erin Blewett.

Inti- In the left corner, one can see Inti, who is the sun god considered the father of the Aymara people and represented by the golden sun. He is a source of warmth, light and life, and he ensures bountiful harvests and prosperity.

Mama Killa- In the right hand corner, one can see Mama Killa, or the moon goddess, who is the sister and wife of Inti. Together with other gods, they represent the foundation of Inca civilization. Mama Killa is associated with fertility, femininity, and cycles of life. She also protects women and children and is invoked during childbirth.

Chacha Warmi- These are the figures at the bottom of the Pachamama. Mamani Mamani says they represents two opposites complementing one another, or man and woman coming from the soil or the earth. The figures reveal the force from each hemisphere to convey there is equilibrium in the world and to call for respect of all that surrounds living things.

González Tinoco emphasizes that the figures reveal the transmutation of animals into people and vice versa. Symbols like the chacha puma (hombre puma) or the chachacondori (hombre condor) speak about the synthesis of humans and animals. Many legends include people who are descendants or kin to sacred animals, and thus, they are half human and half animal as living beings. Some images in the mural capture this belief of animals and humans as one.

González Tinoco further explains the historical significance of these two figures:

The image of the Pachamama houses the figures of an Indigenous man and woman who raise the command of power and the wiphala as leaders who summon the people to their call. Mamani Mamani represents the characters Tupac Katari and Bartolina Sisa as symbols of Indigenous collective rebellion against oppression. It should be remembered that Indigenous insurgency was continuous throughout Spanish colonization, with the Aymara-Quechua rebel cycle of the years 1780-1783 being a precursor to Latin American independence. Various uprisings incited by the Katari brothers, near Charcas; the Tupaq Amaru family, near Cuzco; and Tupac Katari, together with his wife Bartolina Sisa, in La Paz, meant the mobilization of the former kollasuyu against the yoke of colonialism.12

Wiracocha- On the left side of the mural, on the side of the Condor, one can see Wiracocha, or the great creator of the whole Universo Andino (Andean Universe). Rising from water, he is a teacher of the world. Wiracocha was a nomadic God with a magical, messenger bird with gold wings. Wiracocha created men by carving them in stone, and as he gave them names, they took on a life of their own and unfolded in the dark universe before the sun was created.

Wiracocha, with Inti, the sun god, above. Photo by Illampu Aguilar Jove.

Inca Cross or Chakana—In the middle of the Pachamama is the very powerful symbol of Chakana, which has four quadrants and signifies “crossing over” in Quechua. It denotes the interplay between the underground, celestial, and terrestrial or human worlds, as well as the interconnectedness of virtues and values, such as honesty and work.

Symbols of Philadelphia/North America- On the right side, Mamani Mamani painted a skyline of Philadelphia, including Independence Hall, the Philadelphia Art Museum, Ben Franklin Bridge, and other historic buildings. He also included North American Native American symbols such as the Totem Pole.

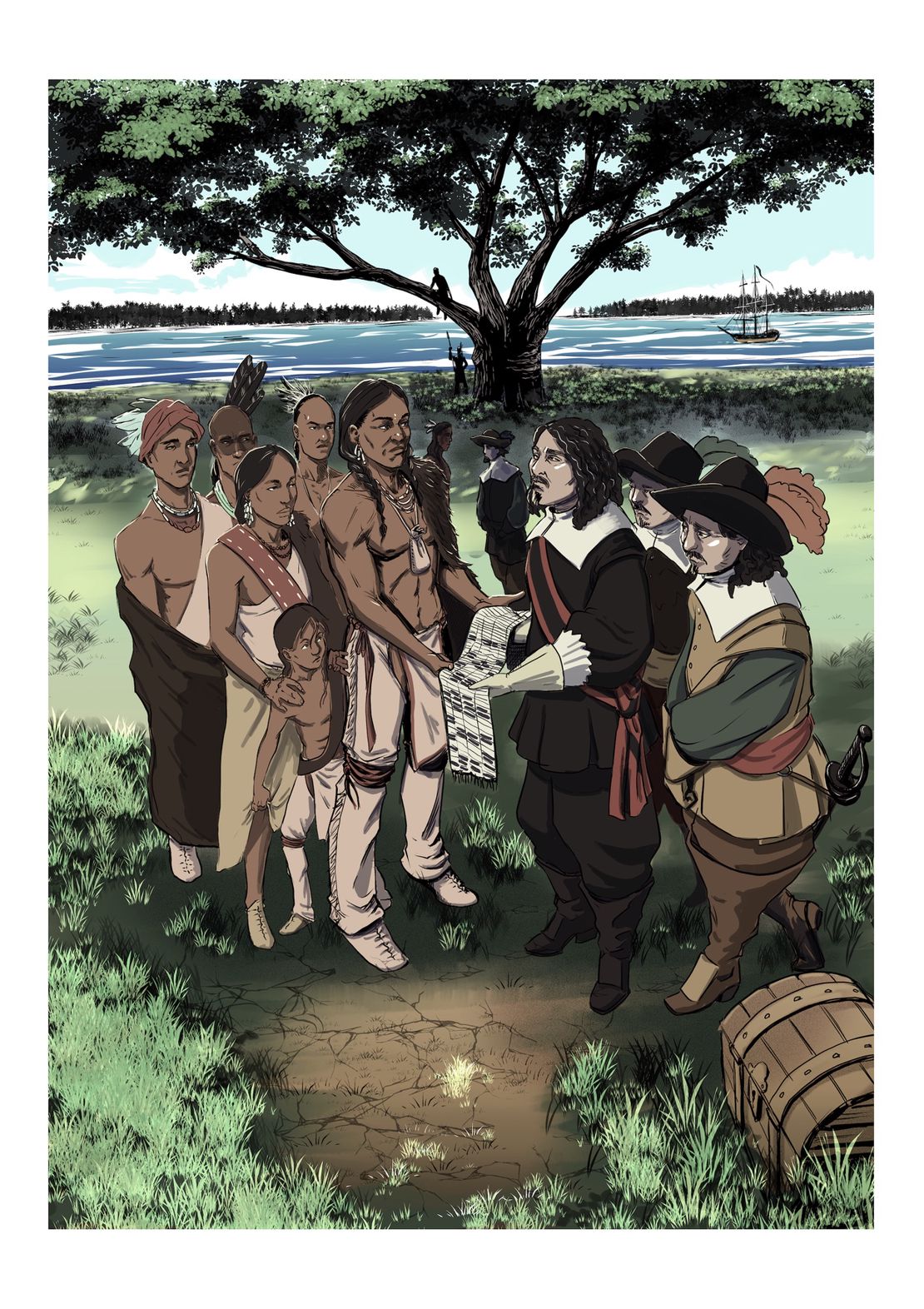

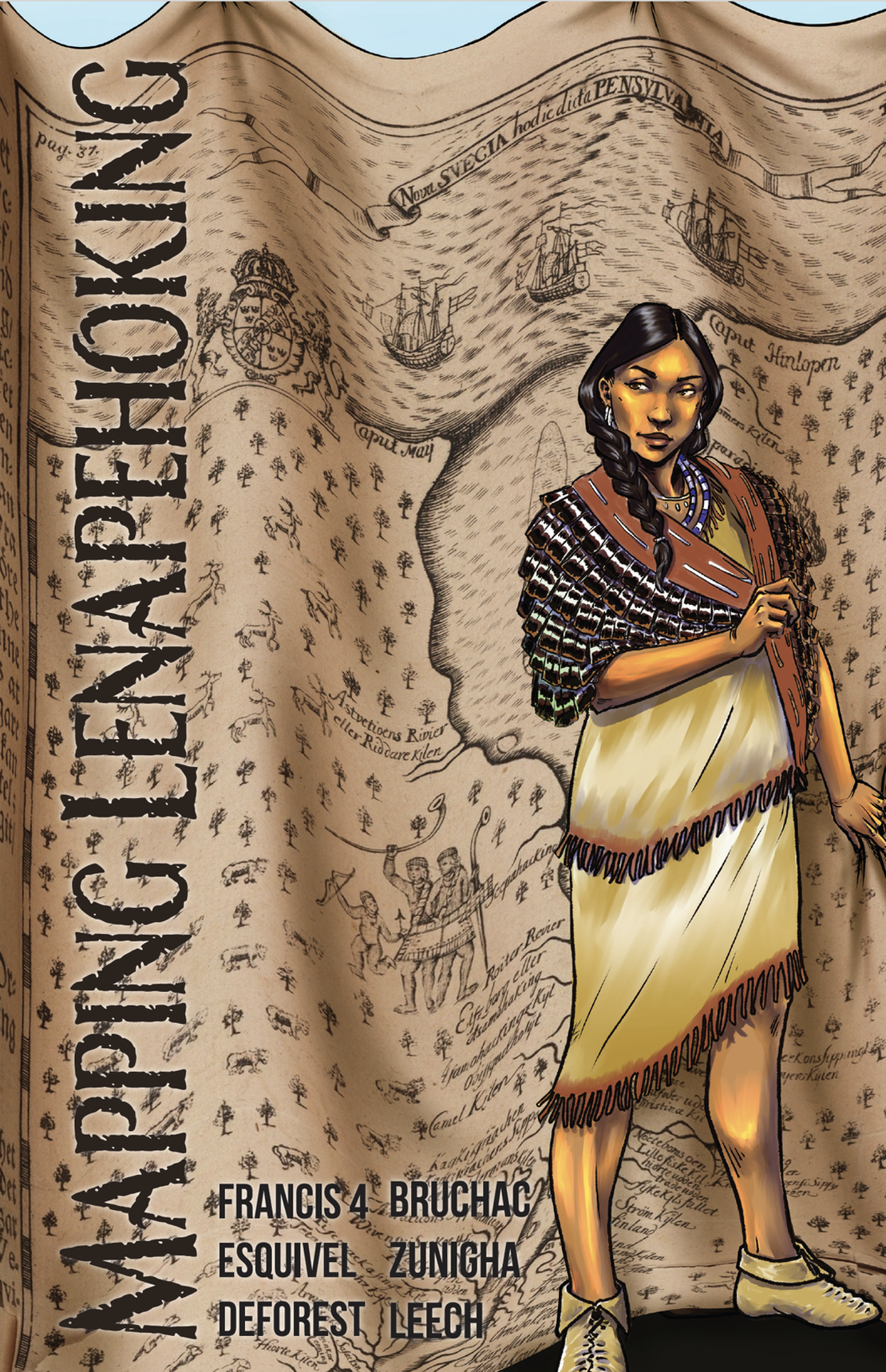

Totem Poles – These are monuments created by Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest to honor Indigenous peoples’ ancestry, history, events. Often they display beings or crest animals to capture histories of families’ rights and privileges. Philadelphia is situated within Lenapehoking, the ancestral homelands of the Lenape peoples.

As you visit the mural, please consider the following questions:

What do you see in the mural?

What can we learn from the Andean cosmovision? How may understanding the stories behind the various symbols shed light on today’s society, here in Philadelphia, abroad in Bolivia, or anywhere in the world?

Why do you think this mural is important for Philadelphia?

What else would you like to learn?

What other messages do you think the artist and his team were trying to convey with this mural?

Send us your pictures! Please send us your pictures of the mural so we can upload them on the “Jallalla” website, which serves as a repository of articles, videos, and other sources that speak to Mamani Mamani’s art and life: https://web.sas.upenn.edu/jallalla/.

Press and references related to the mural:

Acceso Total. “El artista de Bolivia Mamani Mamani muestra el aporte cultural con sus pinturas.” Noticiero 47 Telemundo. October 27, 2023. https://www.telemundo47.com/acceso-total-2/el-artista-de-bolivia-mamani-mamani-muestra-el-aporte-cultural-con-sus-pinturas/2428630/

Center for Latin American and Latinx Studies (CLALS), University of Pennsylvania. “A new mural by Bolivian artist Roberto Mamani Mamani brings the vibrant and powerful energy of the Andes to Philadelphia.” CLALS News. October 4, 2023. https://clals.sas.upenn.edu/news/new-mural-bolivian-artist-roberto-mamani-mamani-brings-vibrant-and-powerful-energy-andes

Center for Latin American and Latinx Studies (CLALS), University of Pennsylvania. “Renowned Bolivian Artist Roberto Mamani Mamani is now in town!” CLALS News. August 30, 2023. https://clals.sas.upenn.edu/news/renowned-bolivian-artist-roberto-mamani-mamani-now-town

Donnelly Johnson, Jenny. “Bolivia’s Roberto Mamani Mamani in Residence.” Mural Arts Website (blog). August 30, 2023. https://www.muralarts.org/blog/bolivias-roberto-mamani-mamani-in-residence/

García, Kristina. “Showcasing an Andean Cosmovision.” Penn Today. October 12, 2023. https://penntoday.upenn.edu/news/Mamani-Mamani-mural-andean-cosmovision-latin-american-studies

González Tinoco, Laura. La Cosmovisión andina y Mamani Mamani. El valor de la imagen como exaltación identitarian indígena. PhD dissertation. Universitat de Barcelona, 2024.

Mikati, Massarah. “Bolivia in Philadelphia: Mural Arts Commissions Renowned Artist Roberto Mamani Mamani.” Philadelphia Inquirer. October 4, 2023. https://www.inquirer.com/arts/roberto-mamino-mural-arts-bolivia-philadelphia-20231004.html

Additional references:

Anez, Arnoldo. “Ideas for Discussion for ‘Applying Andean Philosophies.’” Prepared for a Quechua@Penn and Center for Latin American and Latinx Studies talk on March 19, 2024. Includes cited text about the relationship between the Eagle and the Condor.

Brady, Christy, CPA. City Controller, City of Philadelphia. “Mapping Philadelphia’s Gun Violence Crisis.” 2024. https://controller.phila.gov/philadelphia-audits/mapping-gun-violence/#/?year=2024&map=10.00%2F40.05237%2F-75.15017

Cooper, Kenny. “Philadelphia is America’s Poorest Big City: Here’s What That Actually Means.” WHYY. January 10, 2024. https://whyy.org/articles/philadelphia-americas-poorest-big-city-poverty/#:~:text=Poverty%20is%20as%20synonymous%20with,state%20Senator%20Art%20Haywood%20said.

Ferguson, Britten. “Coca: The Sacred Leaf.” TDA Global Cycling (blog). September 23, 2015, https://tdaglobalcycling.com/2015/09/coca-the-sacred-leaf/

González, Laura Tinoco, 2024. “The value of the indigenous worldview in Mallkuanka. Colorful south-north flight” https://web.sas.upenn.edu/jallalla/. Accessed November 16, 2024.

Gudynas, Eduardo2016. “Buen Vivir: the Social Philosophy Inspiring Movements in South America. https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/blog/buen-vivir-philosophy-south-america-eduardo-gudynas. Accessed November 16, 2024.

Huang, Alice. “What are Totem Poles?” Indigenous Foundations.arts.ubc.ca https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/totem_poles/

Jallalla: Healing and Claiming Indigeneity Through the Arts Website. https://web.sas.upenn.edu/jallalla/

Miniserie. Museo Larco. “Cosmovisión Indígena en las Américas.” https://www.museolarco.org/miniserie/cosmovision-indigena-en-las-americas/ (in English and other languages as well.)

PEW. Philadelphia 2024:The State of the City. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2024/04/philadelphia-2024

Roberto “Mamami Mamani” in front of his depiction of “Pachamamama,” on top the condor (south) and the eagle (north). Photo credit: Bryan Karl Lathrop.

Tulia Falleti, Principal Investigator, speaking at the mural dedication. Photo credit: Bryan Karl Lathrop.

Mural dedication event, September 28, 2023.Photo credit: Bryan Karl Lathrop.

Another view of the mural (it is so large it is hard to capture in single photo!). Photo credit: Bryan Karl Lathrop.

Roberto Mamani Mamani and his collaborators. Photo credit: Bryan Karl Lathrop.

Many thanks to those who contributed ideas, language, editing, and images to this essay, including Américo Mendoza Mori, Arnold Arnez, Dayanna Salas, Bryan Karl Lathrop, Erin Blewett, Ann Farnsworth-Alvear, and Vivian Deidre Rodriguez-Rocha. Special thanks to Laura González Tinoco, an art historian at the University of Barcelona, for her incisive analysis of the mural. ↩︎

Mural Arts Philadelphia. “About.” Accessed November 18, 2024. https://www.muralarts.org/about/ ↩︎

Golden, Jane. Executive Director, Mural Arts Philadelphia. Interview by Cathy Bartch, May 30, 2024. ↩︎

Jane Golden mentioned that only 15% of Mural Arts artists are national or international, as the organization is committed to supporting and commissioning the work of local artists. However, she shared how important it is to bring international artists as well. ↩︎

Oliver Balch, “Buen Vivir: the social philosophy inspiring movements in South America,” The Guardian (London), February, 4, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/blog/buen-vivir-philosophy-south-america-eduardo-gudynas. ↩︎

PEW, “Philadelphia 2024: The State of the City,” accessed November 17, 2024, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2024/04/philadelphia-2024. ↩︎

PEW, “Philadelphia 2024: The State of the City,” accessed November 17, 2024, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2024/04/philadelphia-2024. ↩︎

Also, poverty affects 43 percent of Indigenous peoples in Latin America, and 23 percent live in extreme poverty. World Bank, “Indigenous Latin America,” accessed November 17, 2024. https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/lac/brief/indigenous-latin-america-in-the-twenty-first-century-brief-report-page#:~:text=Poverty%20afflicts%2043%20percent%20of,people%20living%20in%20extreme%20poverty. ↩︎

Patterson, Naeemah, Community Murals Support, Interview by Cathy Bartch. June 1, 2024. ↩︎

Laura González Tinoco “The value of the indigenous worldview in Mallkuanka. Colorful south-north flight” https://web.sas.upenn.edu/jallalla/2024/11/. Accessed November 18, 2024. ↩︎

González Tinoco,“Indigenous worldview in MallkuAnka.” ↩︎

Gonzalez, “Indigenous worldview in Mallkuanka.” See also Víctor Hugo Cárdenas. “La lucha de un pueblo”, in Xavier Albó (Comp.) Raíces de América. El mundo aymara, pp. 499-500. ↩︎