Abstract

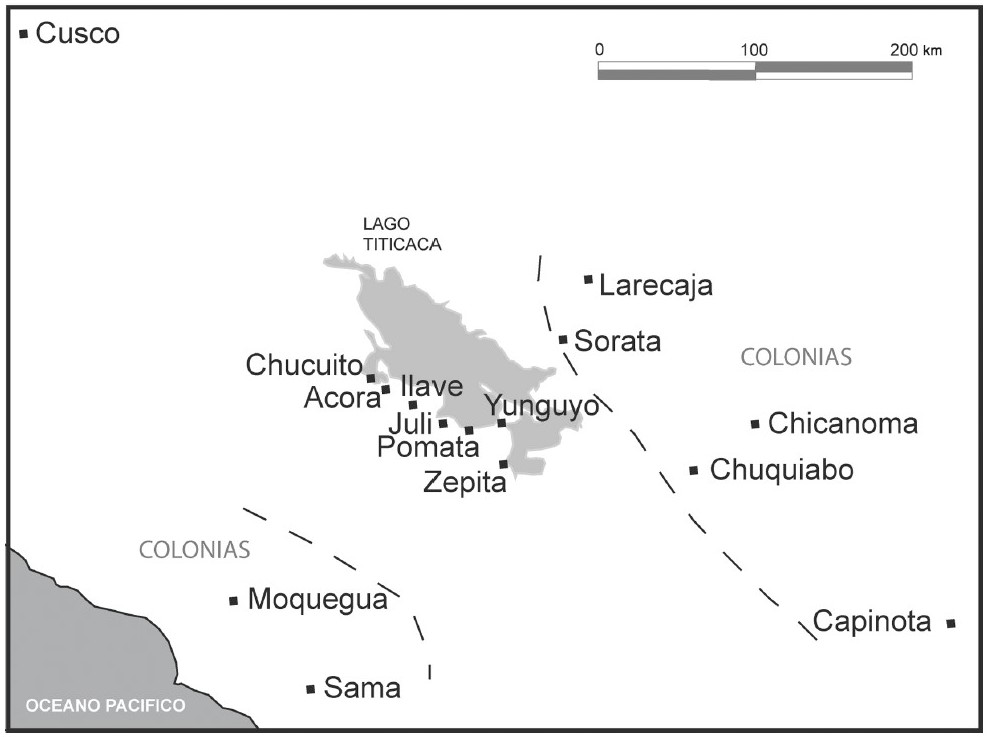

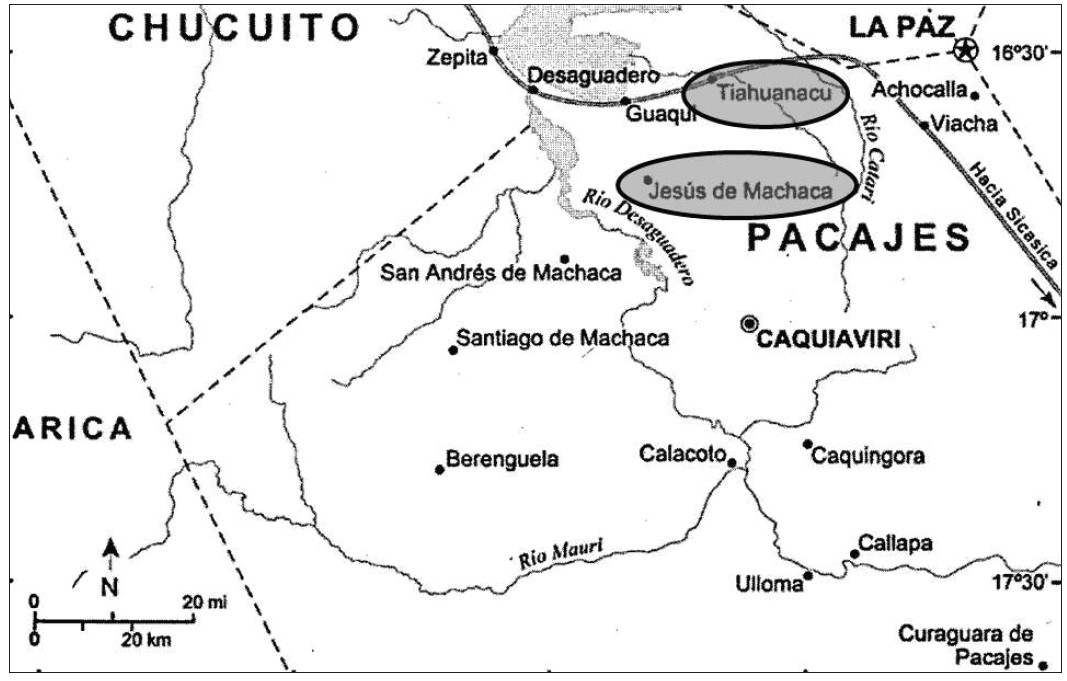

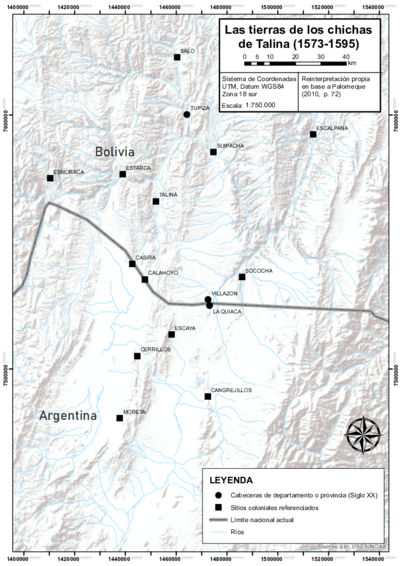

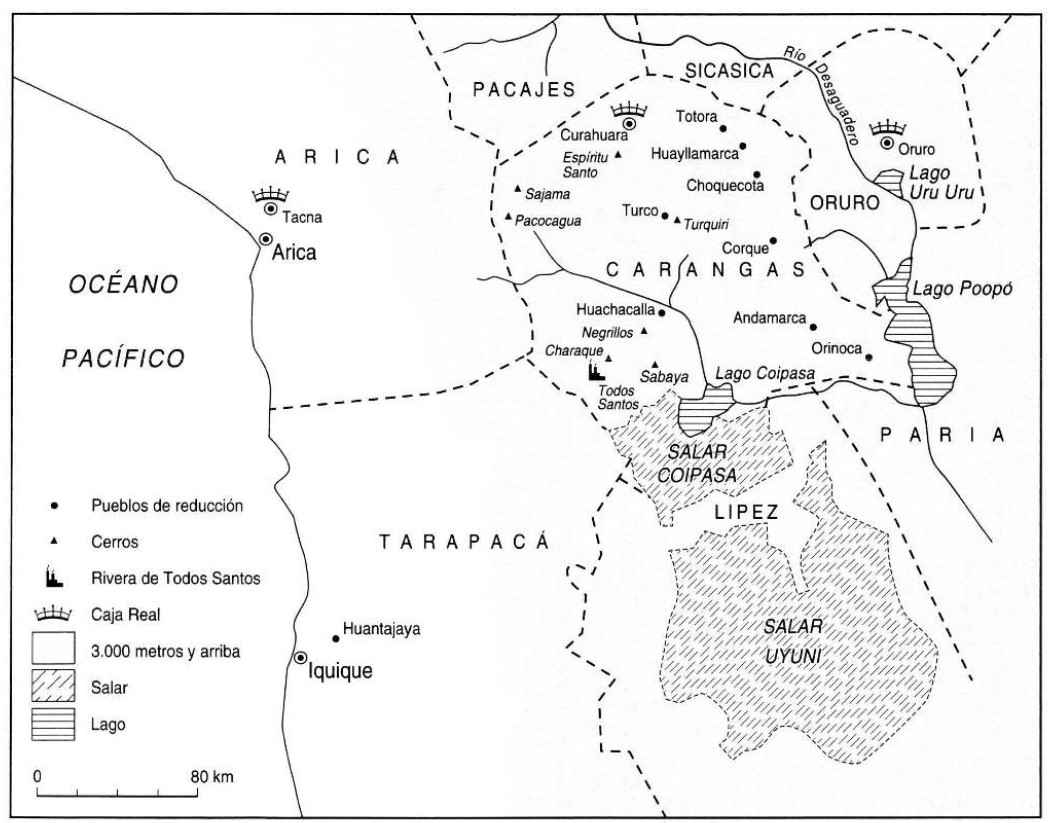

This map shows the approximate borders of the Karanqas (or Carangas or Karankas) Aymara polity territory in the 19th century.1 The Karanqas territory was found at the western end of the great Andean plateau, comprising a mountainous territory to the north and west, undulating in the east, flat and sandy in the center and south; it was bordered to the north by the province of Pacajes, to the east by the province of Paria, to the south by the province of Lipez and to the west by the provinces of Arica and Tarapacá.2 The area had been part of the Qullasuyu, the southern district of the Inca state or Tawantinsuyu and it was the area in which the core settlements of large and powerful Aymara politiessuch as the Lupaqas, Pakaxa, Chichas, or Suras, among many others, were located when the Spanish arrived in the region.

Although the Karanqas have been the subject of extensive academic research it is still difficult to establish their origin given that they suffered significant depopulation and an irreversible fracture in their socio-organizational structure during the colony.3 According to ethnohistoric documents, the formation of this polity had much to do with the development of a local tradition that began in the Formative period (Culture of the Tumuli or Wankarani) and continued until its consolidation before the arrival of the Incas.4

It is documented that Karanqas played a crucial role during the Inca conquest of the Qullasuyu, becoming a strategic territorial point - so much so that no other region of the Bolivian altiplano (except Copacabana, the Isla del Sol and the Isla de la Luna in Lake Titicaca) has the quantity and quality of Inca remains that have been found in the many archaeological investigations in Karanqas. In fact, the alliance forged between the Inca state and the Karanqas had great logistical significance in the expansion of the Tawantinsuyu state towards the Cochabamba valleys and the south of present-day Bolivia.5 It is important to note that when the Spaniards arrived in this region of the altiplano, they encountered a culturally complex landscape because multiple languages were spoken in Karanqas. Although the majority of the population of this socio-political unit communicated in Aymara, it is known that there were also Pukina and Uru speakers; near Oruro, Quechua was also spoken.6

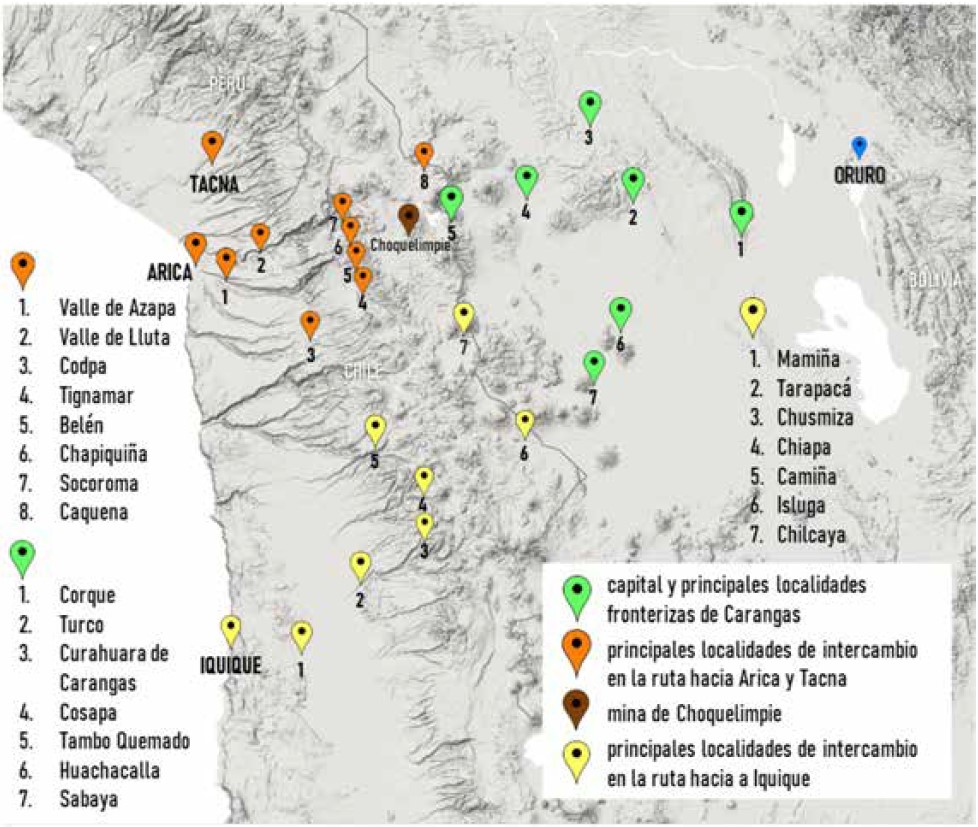

Similar to other Aymara socio-political units, the Karanqas had a dualistic division of space into Urcusuyu (male) and Omasuyu (female), and their social organization was based on kinship ties and social redistribution, with hierarchies of ethnic authorities or lords that governed the group. While not illustrated in this map, following the model of vertical control of ecological niches AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY , the main territory of the Karanqas was located in the central western part of the high plateau but it included ‘ethnic islands’ in the valleys west and east. After Bolivia and Chile established themselves as independent republics in the 19th century, the territory was divided between the two nations. Despite this division, Karanqas trans-border connections persisted and continue to exist today THE KARANQAS AYMARA POLITY - Instant shot of trans-border connections around 1900 (Google Earth adaptation) .

This map not only provides a visual representation of the Karanqas territory but also helps to contextualize the polity’s relationship with the surrounding natural environment. The characteristics of the terrain—mainly above 3,600 meters, semi-desertic, with poor soil and abundant grazing pastures—have profoundly impacted the evolution of the Karanqas where camelid herding and the cultivation of cold-resistant crops formed their economic foundation. Being a pastoralist society, the adaptations and resilience of the Karanqas polity THE KARANQAS AYMARA POLITY UNDER SPANISH COLONIAL RULE IN THE 18TH CENTURY to the colonial regime and into modern times, varies from other Aymara polities once found in the region.7

While having suffered changes inside of the territory during the colonial regime, the Karanqas territory remained mostly unchanged. After independence most of the high plateau territory of the Karanqas became one large province of the department of Oruro. Throughout the 20th century this province has been subdivided into smaller provinces. Nowadays, the Karanqas region is organized into eight provinces, made up of municipalities (formerly cantons) whose boundaries largely coincide with those of the twelve communities or markas or their constituent communities, the ayllus. It is a politically active territory that has managed to maintain over time several aspects of its organizational and cultural structure. Annually, leadership over the ayllu is assigned through a rotating election system to a married couple from the community; they are guided by marka leaders and regional indigenous governing bodies. The latter are the “Consejo Occidental de Ayllus de Jach’a Karangas” (jach’a means “big” in Aymara) or COAJK and the “Consejo Autónomo Nativo de la Nación Nativa de Uru Chipaya” or CAOUC, at the national level represented by the Quechua-Aymara-Uru federation CONAMAQ (Consejo Nacional de Ayllus y Markas del Qollasuyu) that aspires to the reintegration of ancestral indigenous territories.8

REFERENCES:

Cottyn, Hanne. “Entre Comunidad Indígena y Estado Liberal: los ‘Vecinos’ de Carangas

(Siglos XIX-XX).” Boletín Americanista 2, no. 65 (2012): 39-59.

Cottyn, H. “Global land commodification, national land reform and communal land tenure in Carangas (Bolivia), 19th -20th centuries”. Paper presented at the Rural History conference, Bern, 2013.

Cottyn, Hanne. “Carangas en Movimiento: Estado Liberal, Elites Provinciales y

Movilidad Transfronteriza Andina entre el Altiplano Boliviano y el Pacífico

(1860-1930).” Diálogo Andino 66 (December 2021): 261-272.

Gavira-Marquez, M. C. “Población Indígena, Minería y Sublevación en Carangas: La Caja

Real de Carangas y el Mineral de Huantajaya, 1750-1804”, Lima: Instituto Francés

de Estudios Andinos - CIHDE, 2008.

Michel, M. “El Señorío Prehispánico de Carangas.” Thesis of the Advanced Diploma in Indigenous Peoples’ Law. La Paz: Universidad de la Cordillera, 2000.

Montero Montero, R. Gil. “Migración y Minería en el Corregimiento de Carangas (actual Bolivia), Siglo XVII.” Anuario de Historia de América Latina 55 (2018): 190-217.

XIX-XX).” Boletín Americanista 2, no. 65 (2012): 39-59.

Hanne Cottyn, “Entre Comunidad Indígena y Estado Liberal: los ‘Vecinos’ de Carangas (Siglos ↩︎

M. C. Gavira-Márquez, Población Indígena, Minería y Sublevación en Carangas: La Caja Real de Carangas y el Mineral de Huantajaya, 1750-1804 (Lima: Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos – CIHDE, 2008). ↩︎

R. Gil Montero Montero, “Migración y minería en el corregimiento de Carangas (actual Bolivia), siglo XVII,” Anuario de Historia de América Latina 55 (2018): 190-217. ↩︎

M. Michel, “El señorío prehispánico de Carangas.” (Thesis of the Advanced Diploma in Indigenous Peoples’ Law, Universidad de la Cordillera, 2000), 19-20. ↩︎

Michel, “El señorío prehispánico de Carangas”, 85. ↩︎

Michel, “El Señorío Prehispánico de Carangas.”, 16. ↩︎

Cottyn, Hanne. “Carangas en Movimiento: Estado Liberal, Elites Provinciales y Movilidad Trans- Fronteriza Andina entre el Altiplano Boliviano y el Pacífico (1860-1930).” Diálogo Andino 66 (December 2021): 261-272. ↩︎

Cottyn. “Global Land Commodification, National Land Reform and Communal Land Tenure in Carangas (Bolivia), 19th -20th Centuries.” Paper presented at the Rural History conference, Bern, 2013. ↩︎

![Idiáquez, E. (2000 [1894]). «Mapa Elemental de Bolivia». En: INSTITUTO GEOGRÁFICO MILITAR, La Paz](https://dnet8ble6lm7w.cloudfront.net/maps/BOL/BOL0039.jpg)