Abstract

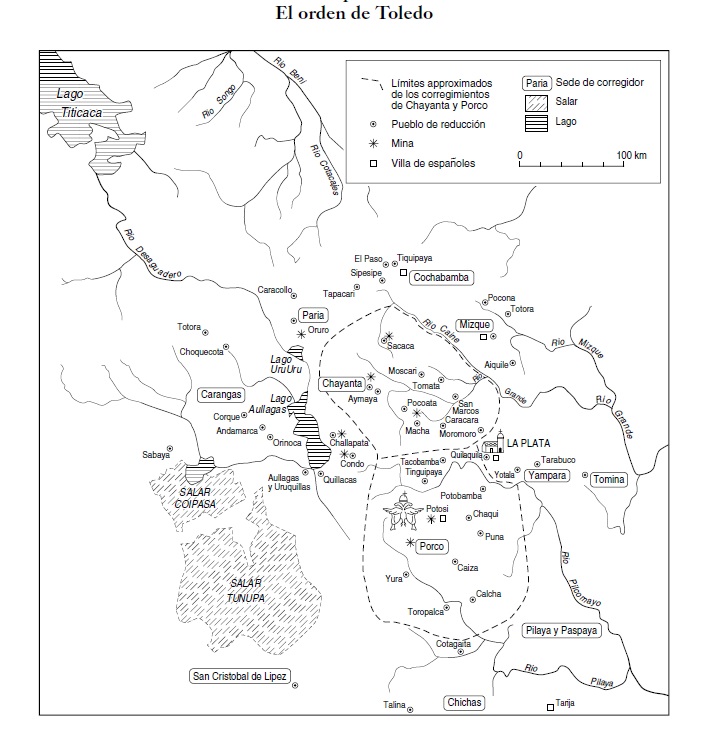

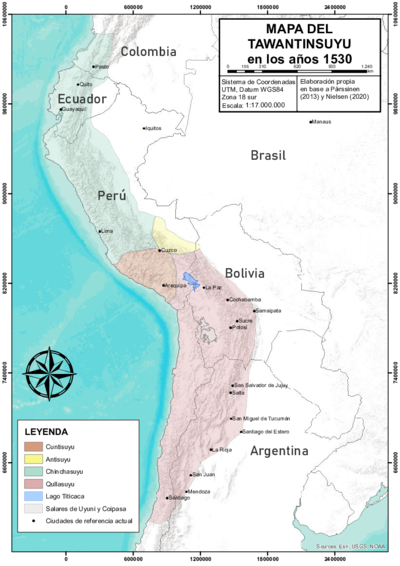

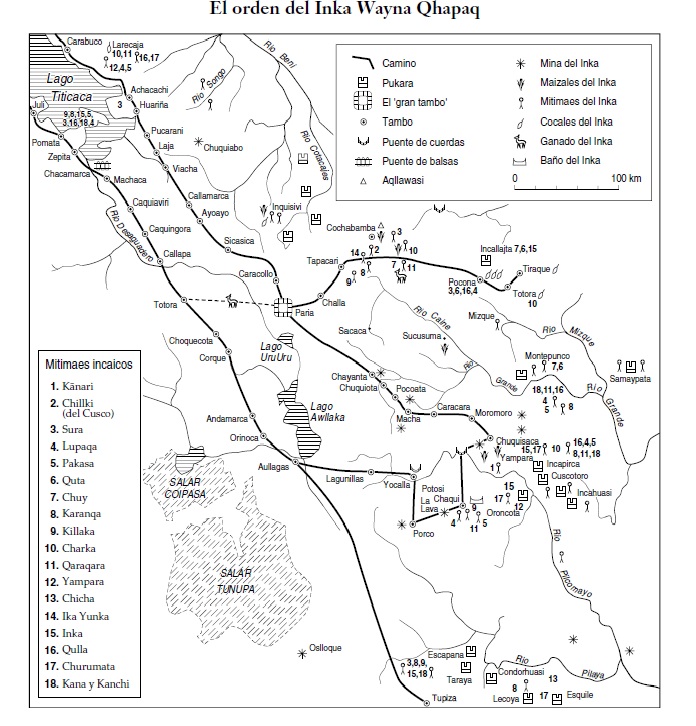

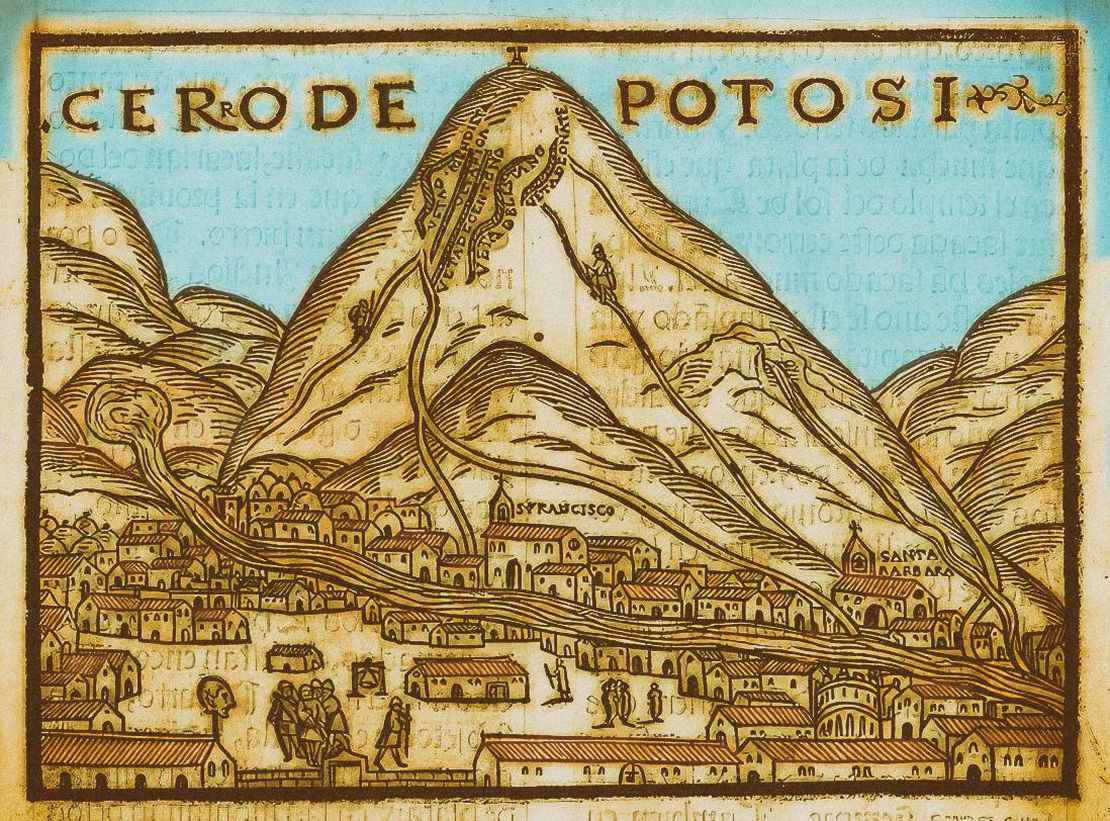

Viceroy Toledo´s reforms represented a new reordering of the Andean region (1569-1581). This map aims to show the transformation of the political-administrative space triggered by these reforms in the new corregimientos, and the displacement of administrative centers from Paria to Chuquisaca and from Cochabamba to Potosí, respectively.1 With a focus on the altiplano and the inter-Andean valleys, more specifically the area around the mines of Potosí, the map illustrates the organization and uses of space under Spanish rule in the 16th century. In pre-colonial times, this region was part of the Qullasuyu, the southern district of the Inca state or Tawantinsuyu. During colonial rule, it became part of the Audiencia de Charcas. Unlike space organization under the Inca rule SPATIAL ORGANIZATION OF THE QULLASUYU UNDER INCA RULE ,during the time as a colony, Potosí became the center of an integrated economic space, thus defining the territorial, administrative and economic organization of this region.

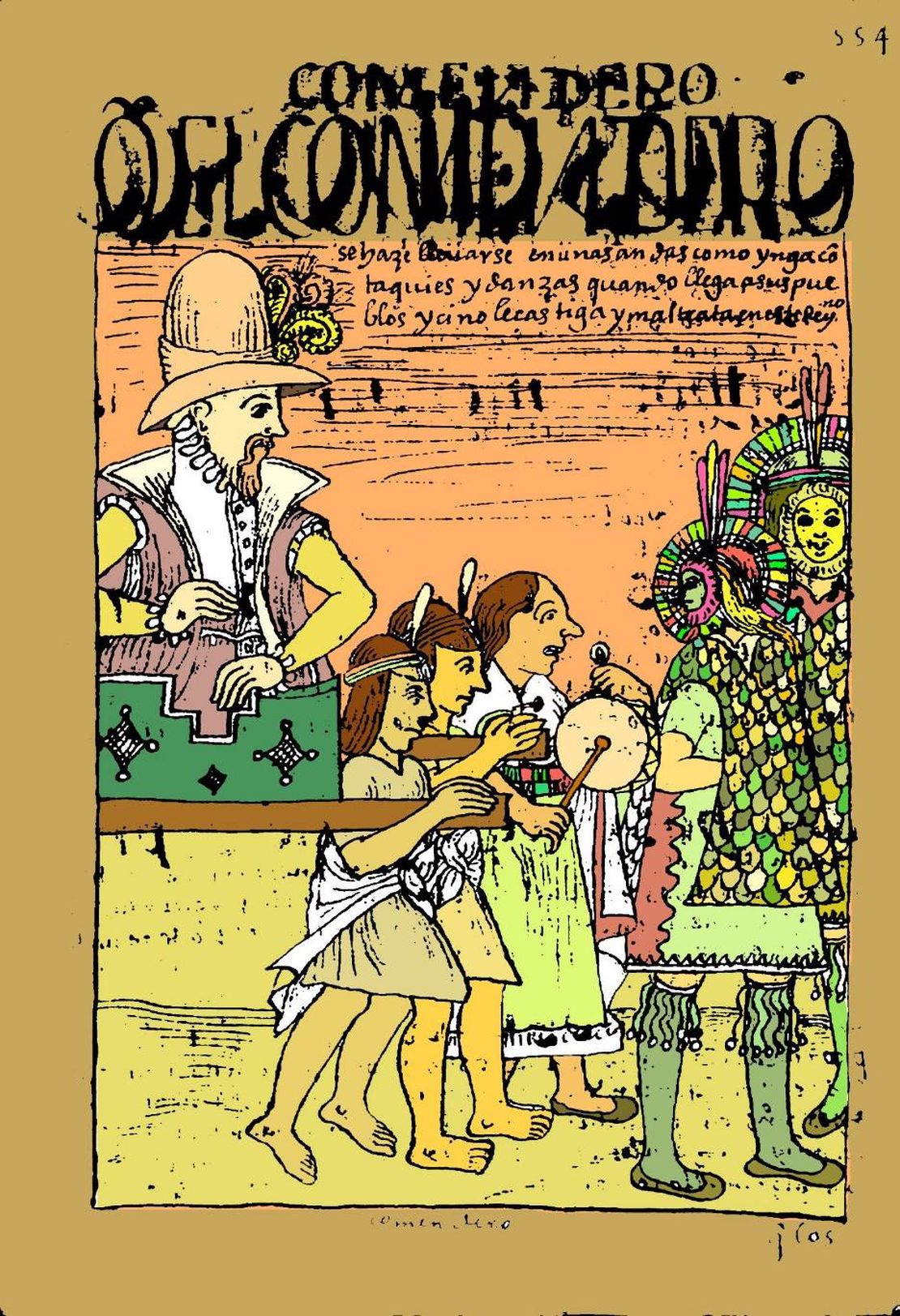

The 1570s stood as an important turning point in the strategies employed by the Spanish Crown to govern both the Spanish colonizers and the colonized Andeans. Pressed by financial needs, concerned about the decline of the silver mines of Potosí, and the evident signs of decay in the native population, the Spanish king ordered Viceroy Toledo (1569-1581) to conduct a general inspection or census, known as Visita General. Through these visits, he sought to readjust the Indigenous tribute, limit the power and privileges of the encomenderos and, above all, revitalize Potosí’s silver production.2 Toledo’s reforms were designed to strengthen Spain´s institutional presence in the Andean region and consolidate the colonial state as an agent of metropolitan interests and direct adjudicator of native resources. The reforms represented the most important set of transformations that the Spanish crown was able to implement in the viceroyalty of Peru.3

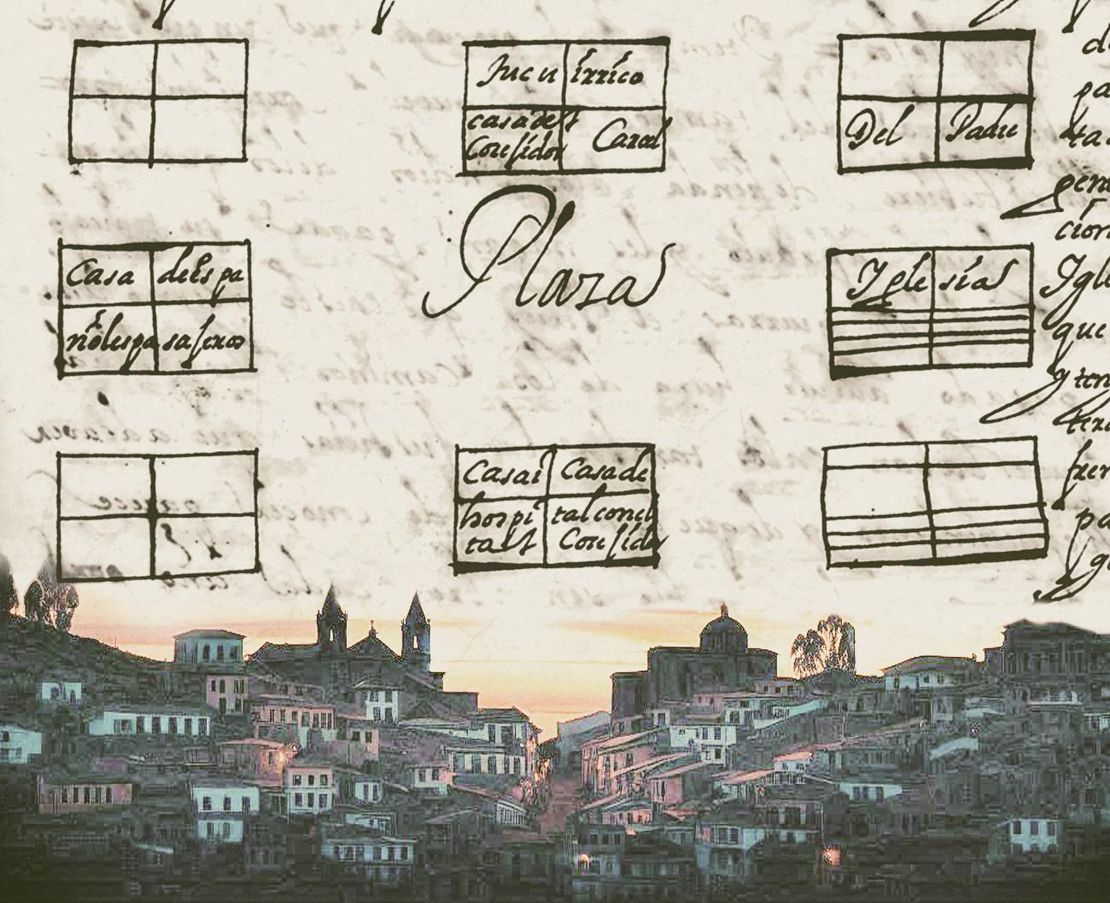

Toledo´s reforms institutionalized and reinforced the political-administrative organization of the viceroyalty territory with better defined borders, significantly reduced the time of encomienda concessions and imposed state officials (corregidores) among the encomenderos, thus sentencing the encomienda to a gradual phase out. More importantly, Toledo launched an ambitious program of massive and forced resettlement of “Indians” in fixed “Pueblos Reales de Indios,” also called Reducciones, which would be governed by ethnic and colonial authorities to manage, evangelize and impose tribute more efficiently. In these Reductions, the ethnic authorities, called kurakas, became officials paid by the state, in charge of collecting tributes under the close supervision of corregidores, parish priests and other colonial officials.

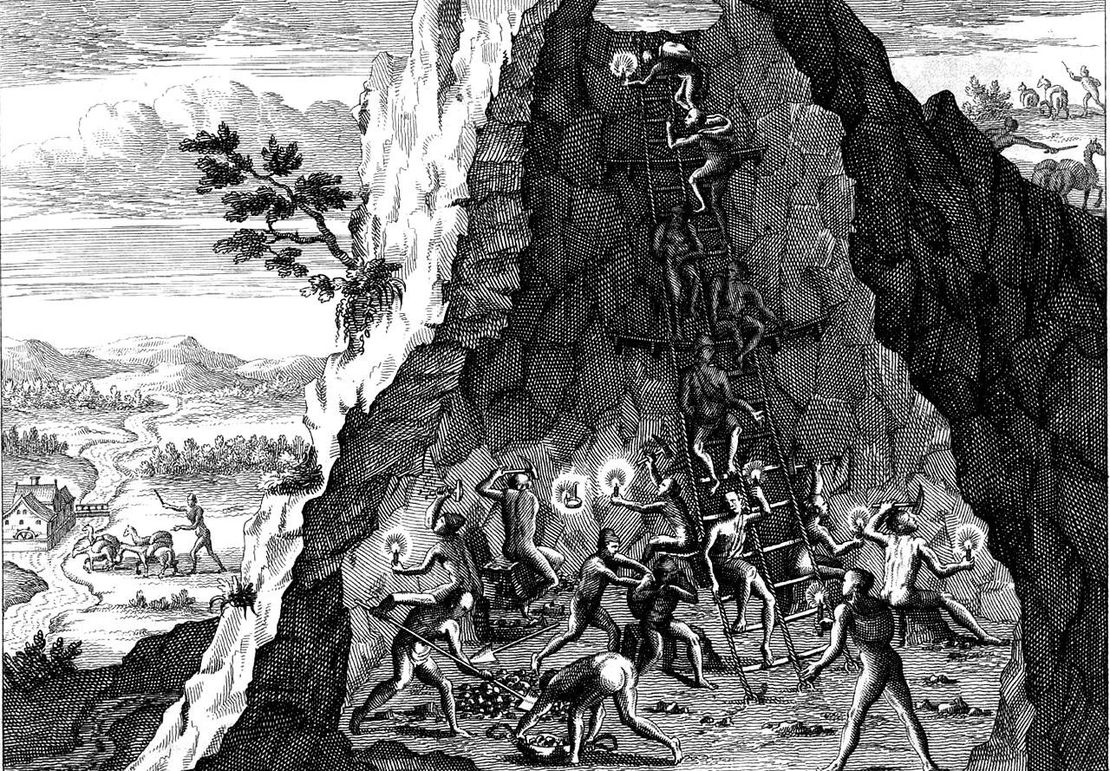

The tax and labor regimes were significantly redesigned, resulting in two main forms of tax collection from the relocated Indians. The first of these was a cash tax per individual to be paid by Indigenous taxpayers or “originarios” —physically fit men between 18 and 50 years old— registered and enrolled in the newly created Pueblos Reales de Indios (Reductions). This rationalization of the tax structure and the monetization of Indian tribute further forced Indigenous peoples into the Spanish economy, waged labor, and the market. The second form of tribute was a system of compulsory labor services, also known as mita, which aimed to solve the labor problem in Potosí´s silver production by turning the recruitment of Indigenous labor into a state enterprise that provided the owners of the Potosí mines with about 13,500 men each year.

Conceived as a —fairly recent— rationalization of the colonial management of territories and populations, and as a systematization of surplus and labor collection mechanisms, the monetization of the Indigenous tribute, the institutionalization of the mita **labor in Potosí, and the forced resettlement program or Reducciones, were the three interrelated reforms that most profoundly affected the territorial and social organization of the Aymara lordships AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY .4 By dismantling what remained of their macro-ethnic territories, the Spanish crown officials “reduced” thousands of small scattered villages to larger integrated towns. Ultimately, the program of forced resettlement and “Indian reduction” led to the fragmentation of the large macro-ethnic polities into a multiplicity of “Indian royal towns” which, as re-formed ayllus, became the main reference for the molding of new ethnic identities and claims. In time, they would be commonly referred to as “Indian communities.”5

REFERENCES:

Abercrombie, Thomas. Pathways of Memory and Power: Ethnography and History among an Andean People. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998.

Cook, Noble David, ed. Tasa de la Visita General de Francisco de Toledo. Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 1975.

Larson, Brooke. Colonialismo y Transformación Agraria en Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990. La Paz: Vicepresidencia del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2017.

Platt, Tristan, Thérèse Bouysse-Cassagne and Olivia Harris. Qaraqara-Charka:

Mallku, Inka, and King in the Province of Charcas (XV - XVII centuries): History

Antropológica de una Confederación Aymara. La Paz: Plural-IFEA, 2006.

Zagalsky, Paula. “El Concepto de ´Comunidad´ en su Dimensión Espacial. Una

Historización de su Semántica en el Contexto Colonial Andino (Siglos XVI-XVII)”. Revista Andina, 48 (2009): 57-90.

San Marcos, 1975).

(Vice Presidency of the Plurinational State of Bolivia, 2017).

Tristan Platt, Thérèse Bouysse-Cassagne, and Olivia Harris, Qaraqara-Charka: Mallku, Inka and King in the Province of Charcas (15th - 17th centuries): Anthropological History of an Aymara Confederation (La Paz: Plural-IFEA, 2006), 488. ↩︎

Noble David Cook, Tasa de la Visita General de Francisco Toledo (Universidad Nacional Mayor de ↩︎

Brooke Larson, Colonialismo y Transformación Agraria en Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990. ↩︎

Larson, Colonialismo y Transformación Agraria en Bolivia: Cochabamba 1550-1990. ↩︎

Zagalsky, Paula. “El Concepto de ´Comunidad´ en su Dimensión Espacial. Una Historización de su Semántica en el Contexto Colonial Andino (Siglos XVI-XVII). Revista Andina, 48 (2009): 57-90. ↩︎