Abstract

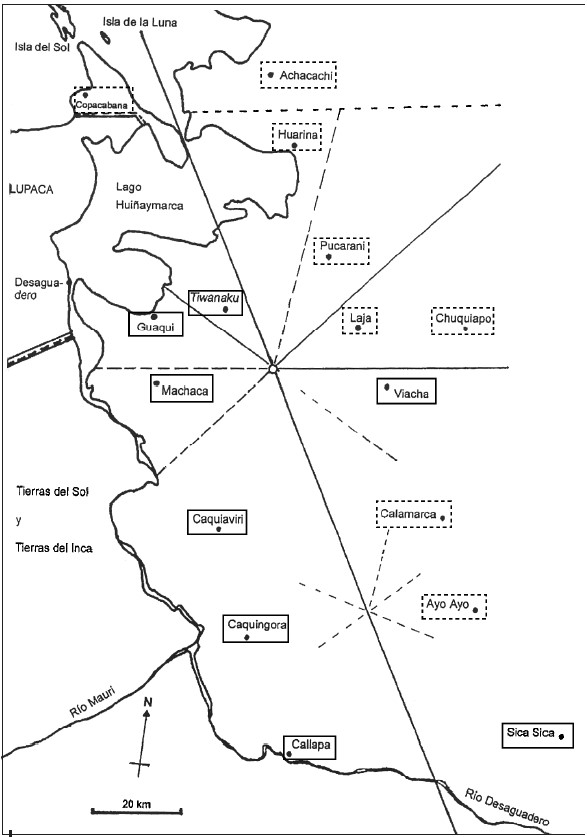

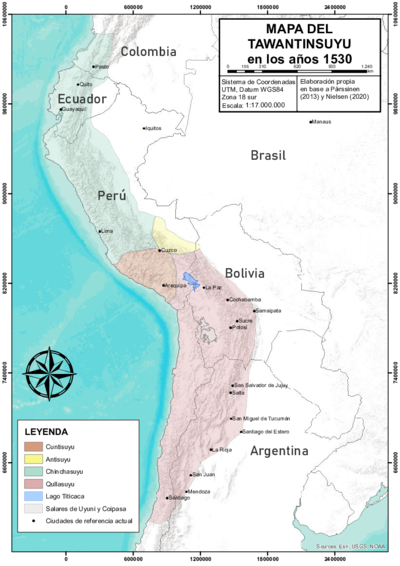

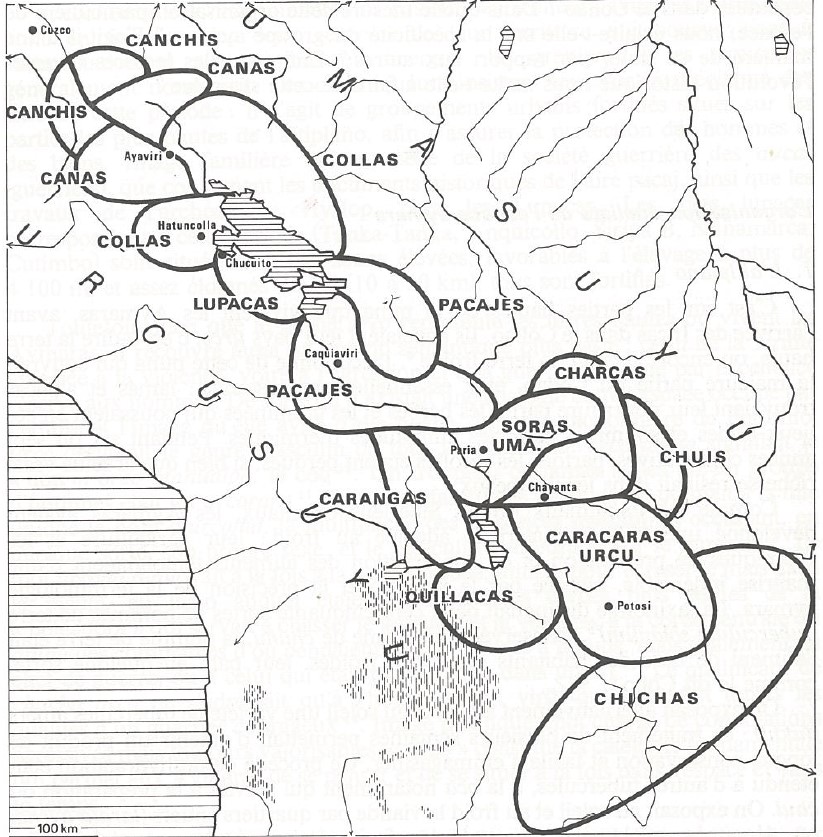

The map shows the nucleated ‘Indian Royal Towns’ established by the Spanish colonial state, through a massive forced resettlement program, in a portion of the territory of the Aymara polity of the Pakaxa (Paka Jaqi or Pacajes) located on the high plateau near the southern tip of the Titicaca lake (in present day Bolivia).1 Before Spanish colonization, this area was part of theQullasuyu, the southern district of the Inca state or Tawantinsuyu and it was the area in which the core settlements of the large Aymara polity of the Pakaxa were located (upper moiety or Urqu Pakaxa). Viceroy Toledo’s design and institutionalization of the colonial mita draft labor system was based partially on pre-hispanic territoriality and political organization, as can be seen in this map in which the Andean Aymara dualist conception of space AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY is perfectly illustrated.

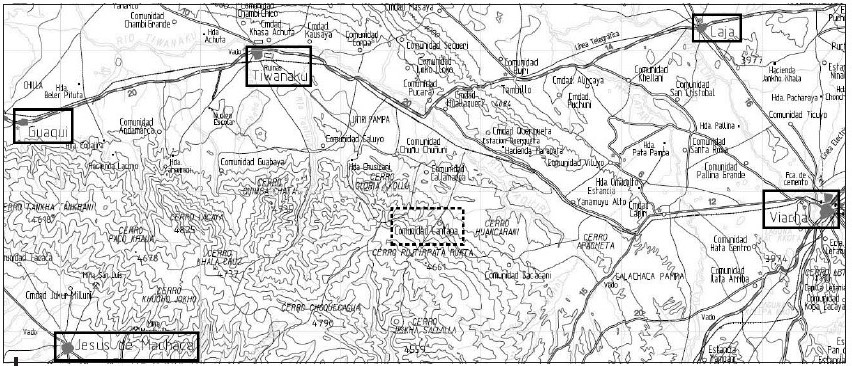

Following the dualist conception of space, Viceroy Toledo established two captaincies which were territorial and/or population units. These units encompassed tributary populations subjected to the mita draft labor system within specific areas, overseen by mita captains who were indigenous authorities responsible for ensuring compliance with mita obligations among their jurisdiction’s mita workers (mitayos). These captaincies are portrayed in the map: the first, Pacajes urqu, hierarchically superior, included the districts of Callapa, Caquingora, Caquiaviri, Machaca la Chica, Machaca la Grande, Guaqui, Tiwanaku, Viacha, Sica Sica, and Caracollo (here shown with a solid line); while the second, Pacajes uma, hierarchically inferior, included the districts of Achacachi, Guarina Pucarani, Laja, Chuquiabo, Copacabana, Calamarca and Ayo Ayo (here shown with a dotted line).

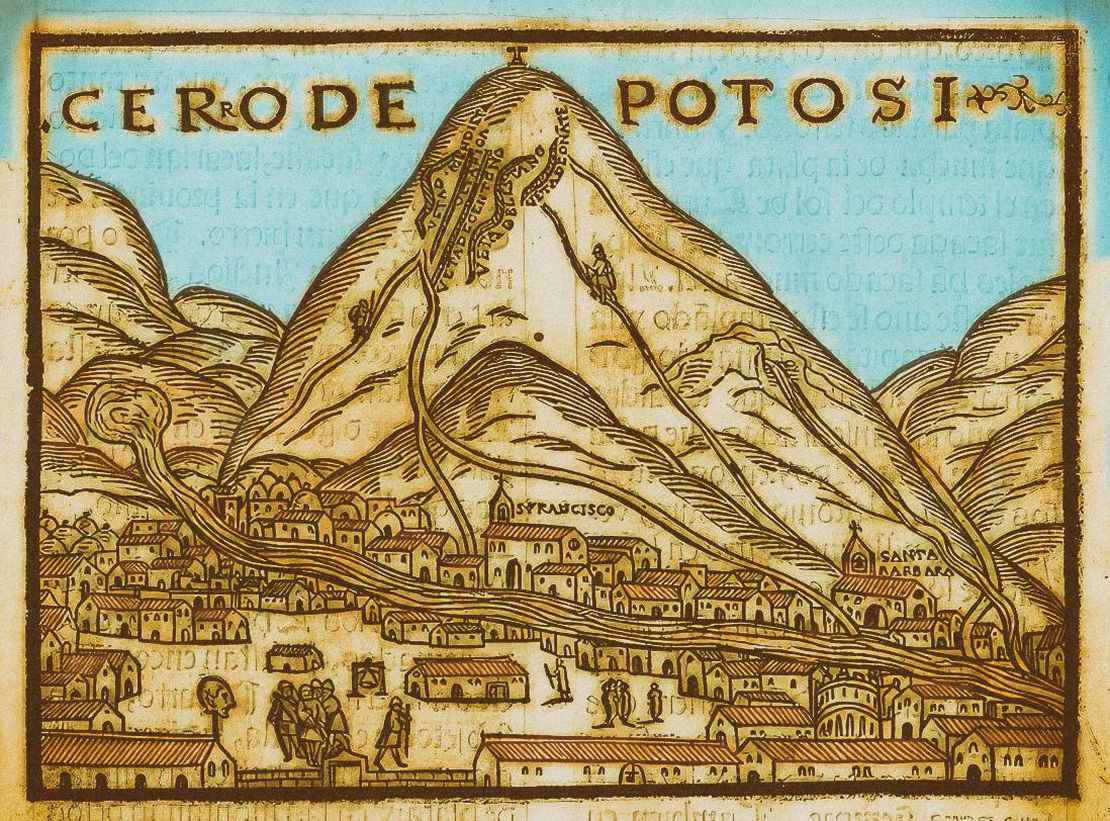

In addition, this map highlights both the sacred center of Cantapa ‘INDIAN ROYAL TOWNS’ (REDUCCIONES) AND SACRED SPACES UNDER SPANISH COLONIAL RULE IN THE TERRITORY OF THE PRE-COLONIAL AYMARA POLITY OF THE PAKAXA IN THE LATE 16TH CENTURY and that of Topohoco. According to Morrone, Topohoco was a second central sacred place, supporting the hypothesis of two symbolically central points in a balanced dualism. These points might had been established under Inca rule and later redefined by colonial authorities for organizing the mining mita draft labor system for the mines of Potosi. This redefinition perhaps mirrored existing differences, hierarchies, and precedence. It was not coincidental that the colonial government strategically selected these two central nodes for recruiting and concentrating the mita workforce before sending them to Potosí. These nodes likely served a similar function for the mit’a during the Tawantinsuyu era.2

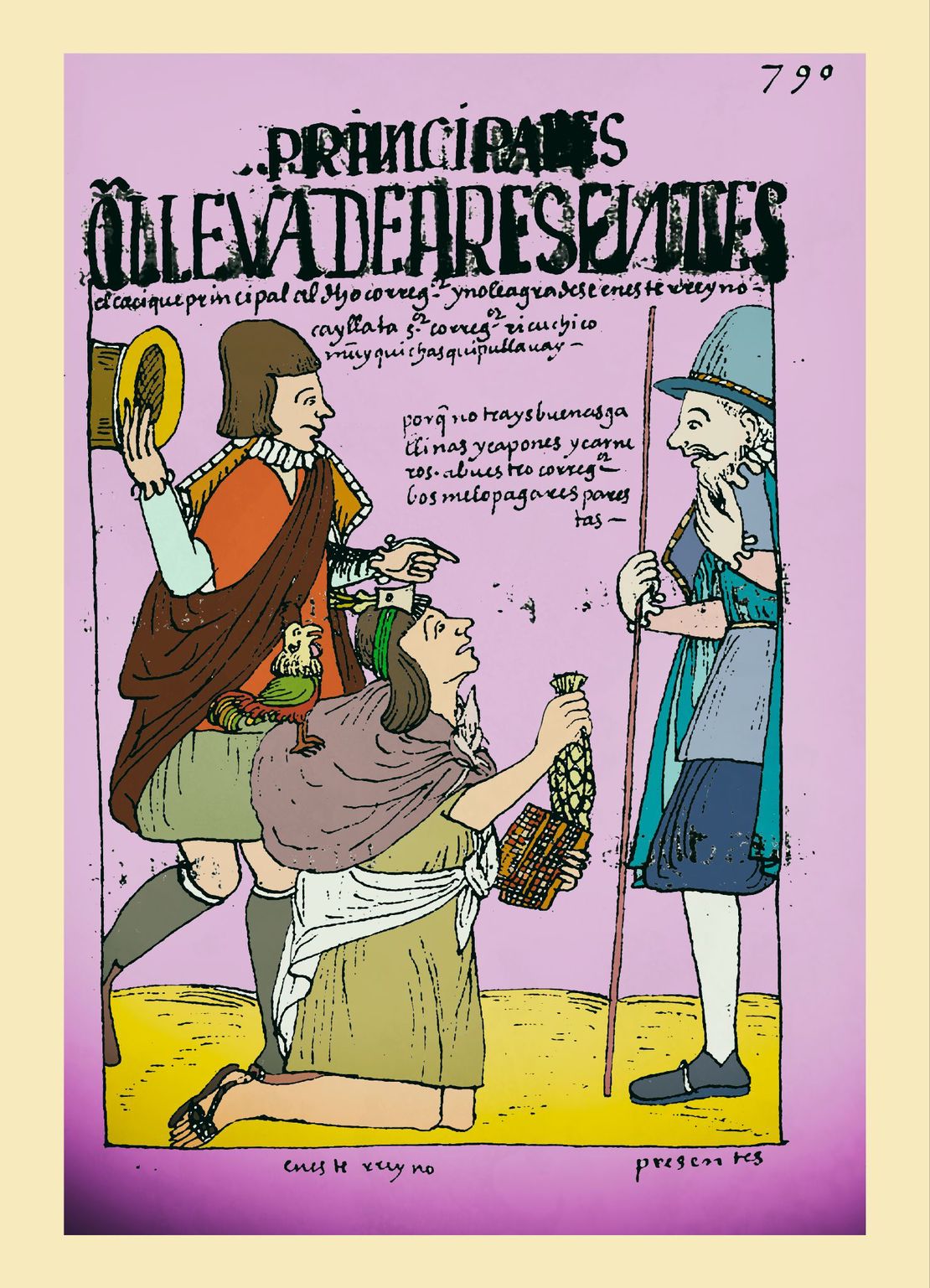

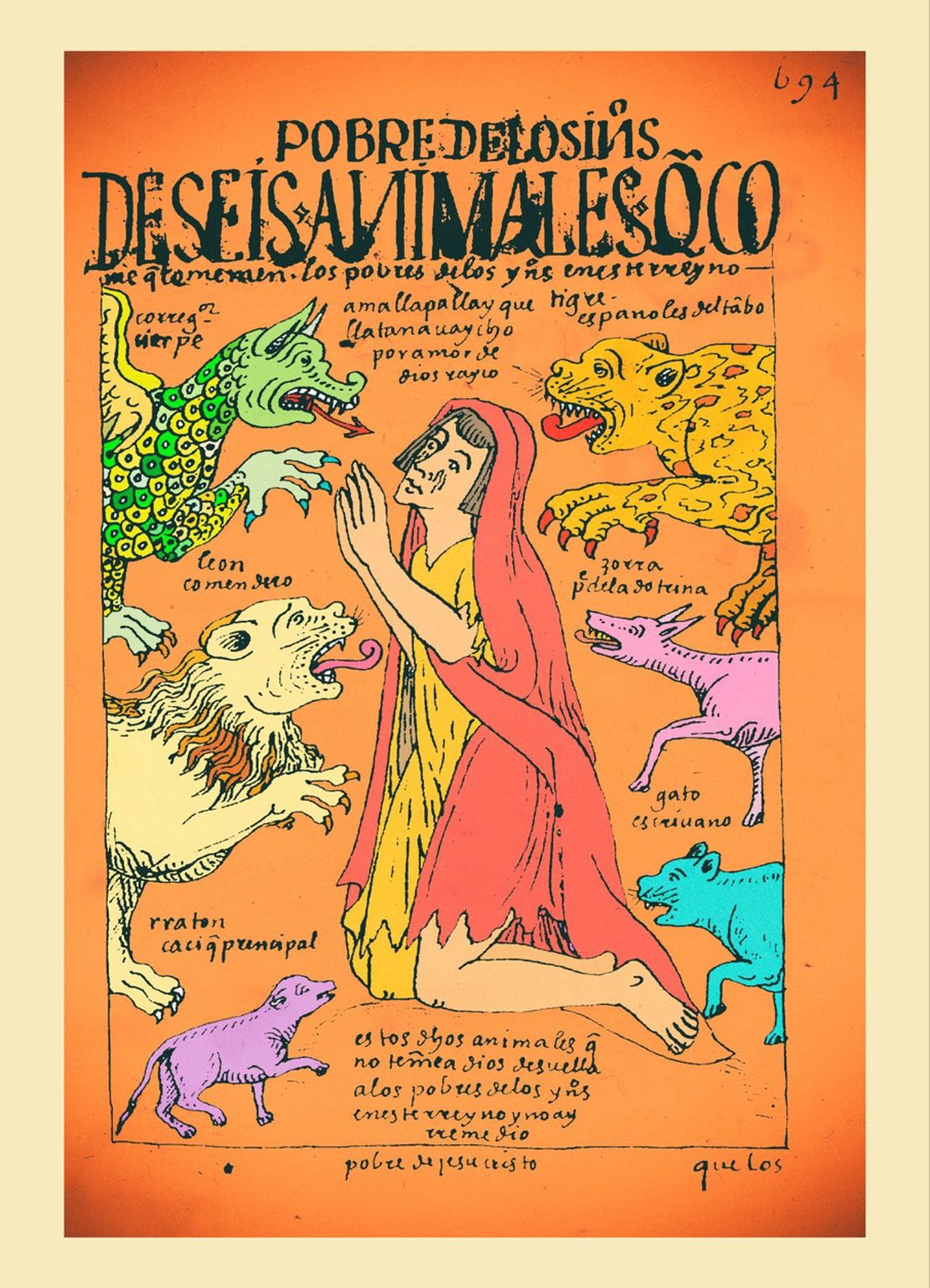

As happened elsewhere, the mita coupled with the ‘Indian’ tribute signified a heavy burden on the indigenous population. With time, mitayos decided not to return to their native land as a strategy for avoiding the mita draft and the tribute – some of them retiring to as far Arica (present-day Chile). By the 17th century, many towns such as San Andrés de Machaqa, Julluma, Waqi, Tiwanaku, and Santiago de Machaqa were literally abandoned; this process created a series of conflicting situations between the tributary population and their caciques and the colonial political and administrative authorities.3 By the 18th century, besides the tribute and the mita, indigenous peoples were forced to buy commodities under what became known as “repartos”. Whether they needed or wanted these products, indigenous were forced to buy clothings, livestock, wine etc at prices fixed by the colonial authorities. This abuse was one of the main catalysts of the Amaru and Katari 1780s rebellions in which the Pakaxa participated actively.4

REFERENCES:

Bouysse-Cassagne, Thérèse. “L’Espace Aymara: Urcu et Uma.” Annales Economies

Societes Civilizations, 33, no. 5-6 (December 1978): 1057-1080.

Choque, Roberto, Jesús de Machaca: La Marka Rebelde. 2nd ed., vol 1. La Paz: CIPCA, 2003.

Morrone, Ariel. “Tras los Pasos del Mitayo: La Sacralización del Espacio en los

Corregimientos de Pacajes y Omasuyos (1570-1650).” Boletín del Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, 44, no. 1 (April 2015): 91-116.

Ariel Morrone, “No Todos los Caciques fueron Mallku: Mediación Política Truncada en los Corregimientos de Pacajes y Omasuyos (Audiencia de Charcas 1570 - 1630).” Diálogo Andino 50 (June 2016): 207-217. ↩︎

Morrone, “No Todos los Caciques fueron Mallku: Mediación Política Truncada en los Corregimientos de Pacajes y Omasuyos (Audiencia de Charcas 1570 - 1630),”104. ↩︎

Roberto Choque, *Jesús de Machaca: La marka rebelde. (*La Paz: CIPCA, 2003), 167-168. ↩︎

Choque, Jesús de Machaca: La Marka Rebelde, 174. ↩︎