Abstract

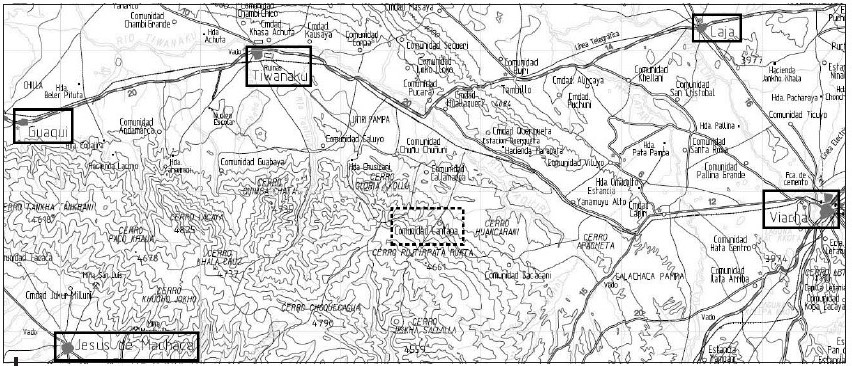

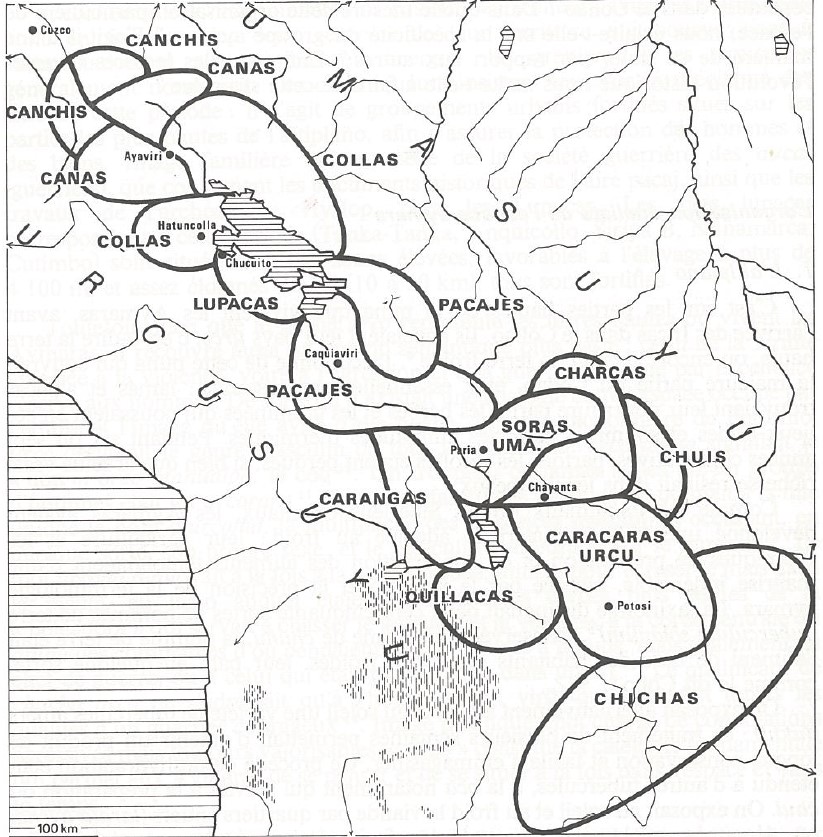

The map shows the nucleated ‘Indian Royal Towns’ established by the Spanish colonial state, through a massive forced resettlement program, in a portion of the territory of the Aymara polity of the Pakaxa (Paka Jaqi or Pacajes) located on the high plateau near the southern tip of the Titicaca lake (in present day Bolivia).1 Before Spanish colonization, this area was part of the Qullasuyu, the southern district of the Inca state or Tawantinsuyu and it was the area in which the core settlements of the large Aymara polity AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY of the Pakaxa were located (upper moiety or Urqu Pakaxa). Under Spanish colonial rule, the Qullasuyu became the southern district of the Viceroyalty of Peru called Distrito de la Audiencia de Charcas or La Plata divided into two large provinces, Charcas and La Paz. The area on the map was part of the latter which was further divided into smaller territorial administrative units. The territorial units (sort of rural districts) assigned to the indigenous population were called Corregimientos de Indios. The area shown on the map became the Corregimiento of Pacajes and encompassed a number of ‘Indian Royal Towns’ also called reducciones represented by the dots on the map and marked with boxes.

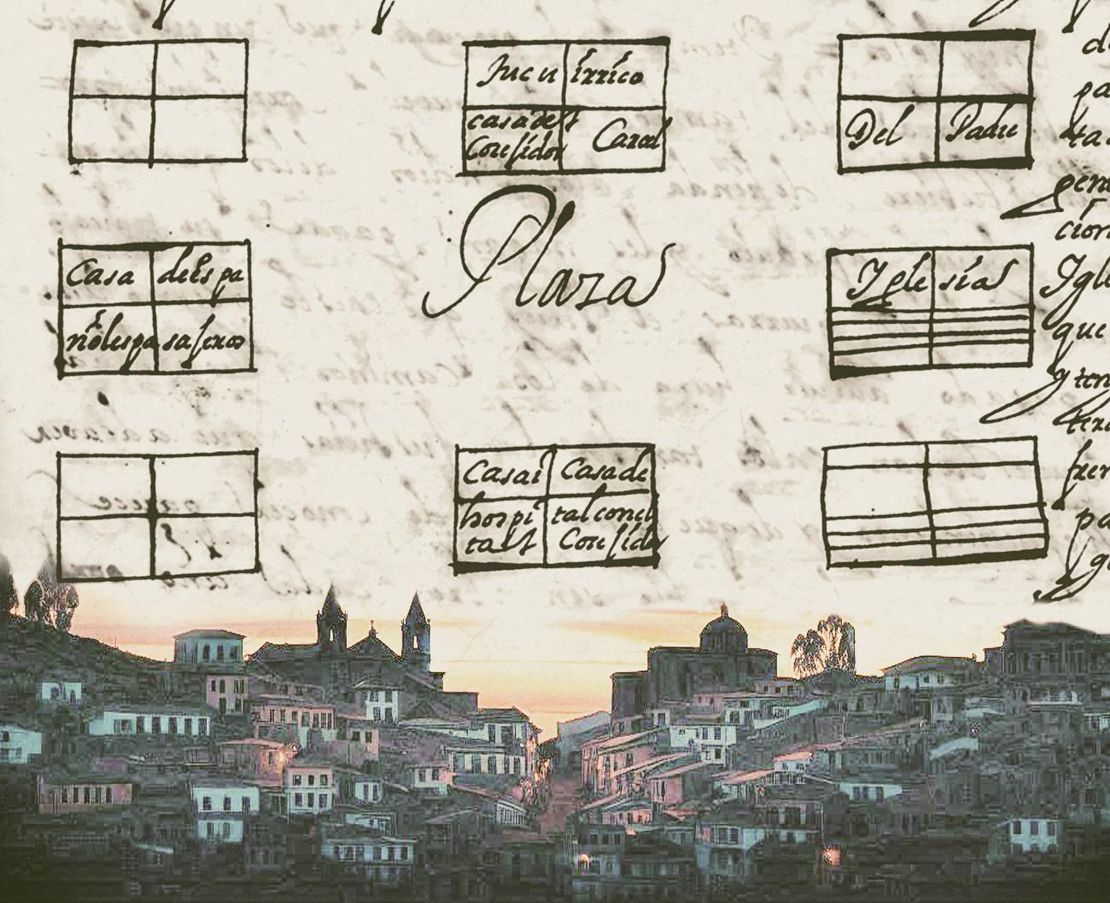

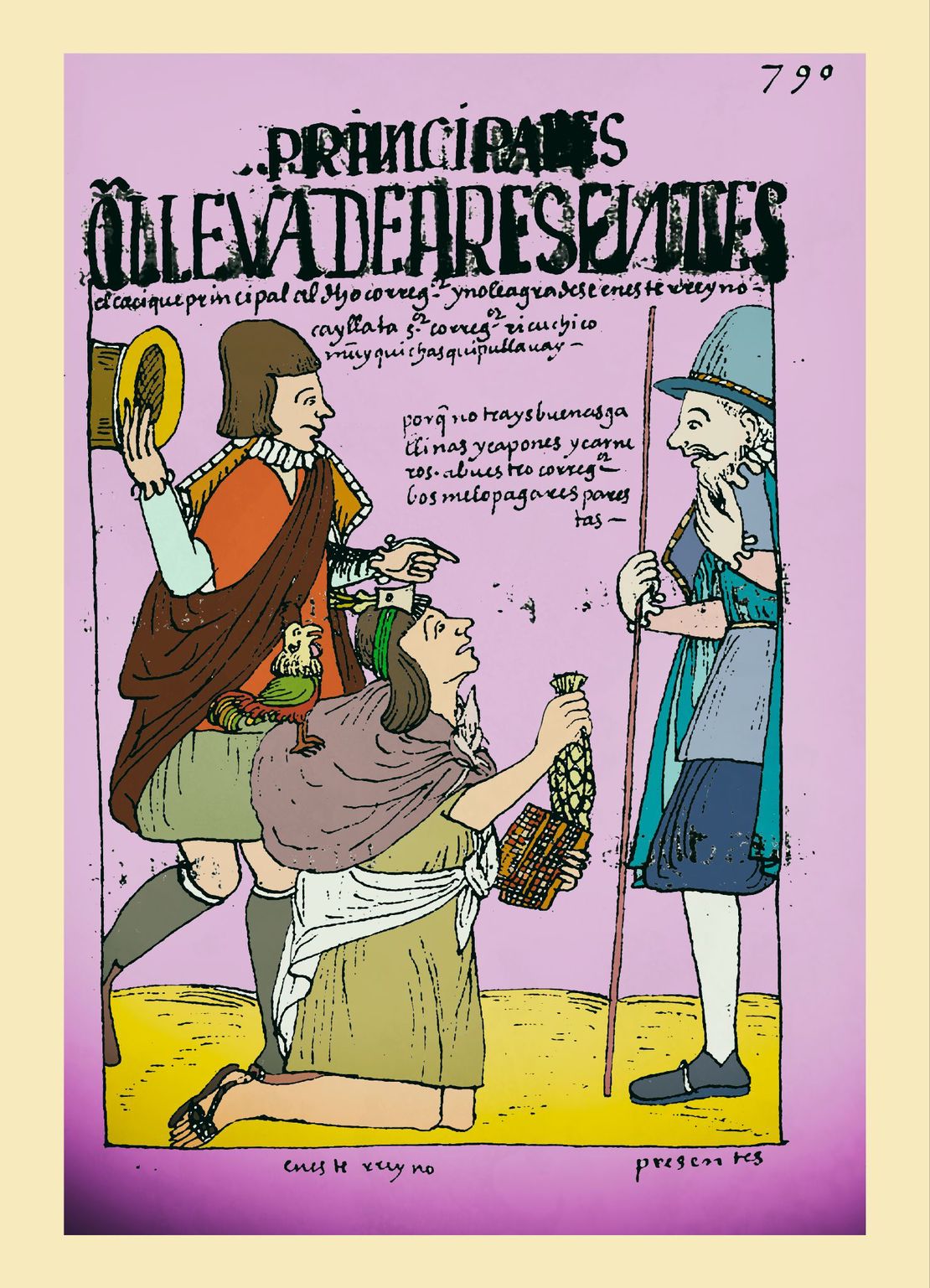

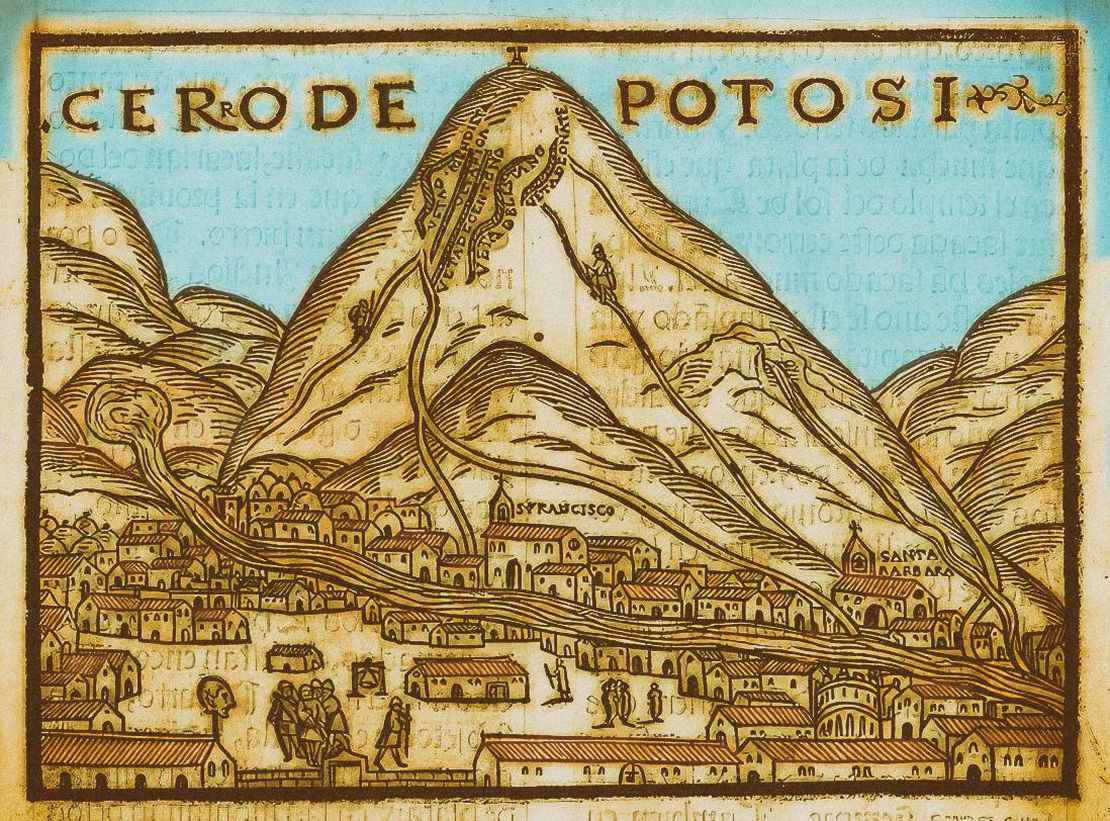

In these so called Indian Royal Towns or ‘reducciones’ ethnic authorities were to become state paid functionaries in charge of collecting tribute and delivering levied labor under the close supervision of parish priests, and other colonial officials. Dismantling what was left from pre-Columbian ethnic territories and stripping the Aymara polities from their traditional land rights, Spanish colonial officials drove people away from their ancient lands. Toledo also implemented the draft labor system COLONIAL LEGISLATIONS AS A FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE COLONIAL MITA known as the mita to lower the cost of indigenous labor in the mines of Potosí whose recovery was of utmost importance to the colonial state.

With this map we gain perspective into the fact that there were important territorial landmarks in the Pakaxa territory. In this case, these landmarks often encapsulated collective memory, ancestry, and cult, and defined borders between segments like ayllu, partiality, and marka (i.e. the units of internal organization of this aymara polity). In order to re-organize space in the resettlement process for the reducciones, the Spanish administration had to first consider these patterns of social occupation of the territory. And while these borders were reorganized during colonial reducciones, they remained crucial markers of physical space and collective ancestral memory2. Interestingly enough, the ethnic authority of the cacique would strategically activate this memory during negotiations to retain significant portions of their land. Cantapa which is portrayed in the middle of the map, for instance, was central to a network of imaginary lines similar to the Cuzco ceques, used by the Inca to mark boundaries for the Pakaxa groups. Conflicts over this territory likely stemmed from Cantapa’s significance as a space of ritual and political power. Similarly, the transfer of mitayos (mita workers) from their ‘Indian Royal Towns’ to the Potosí mines was done using ritual paths and spaces.3

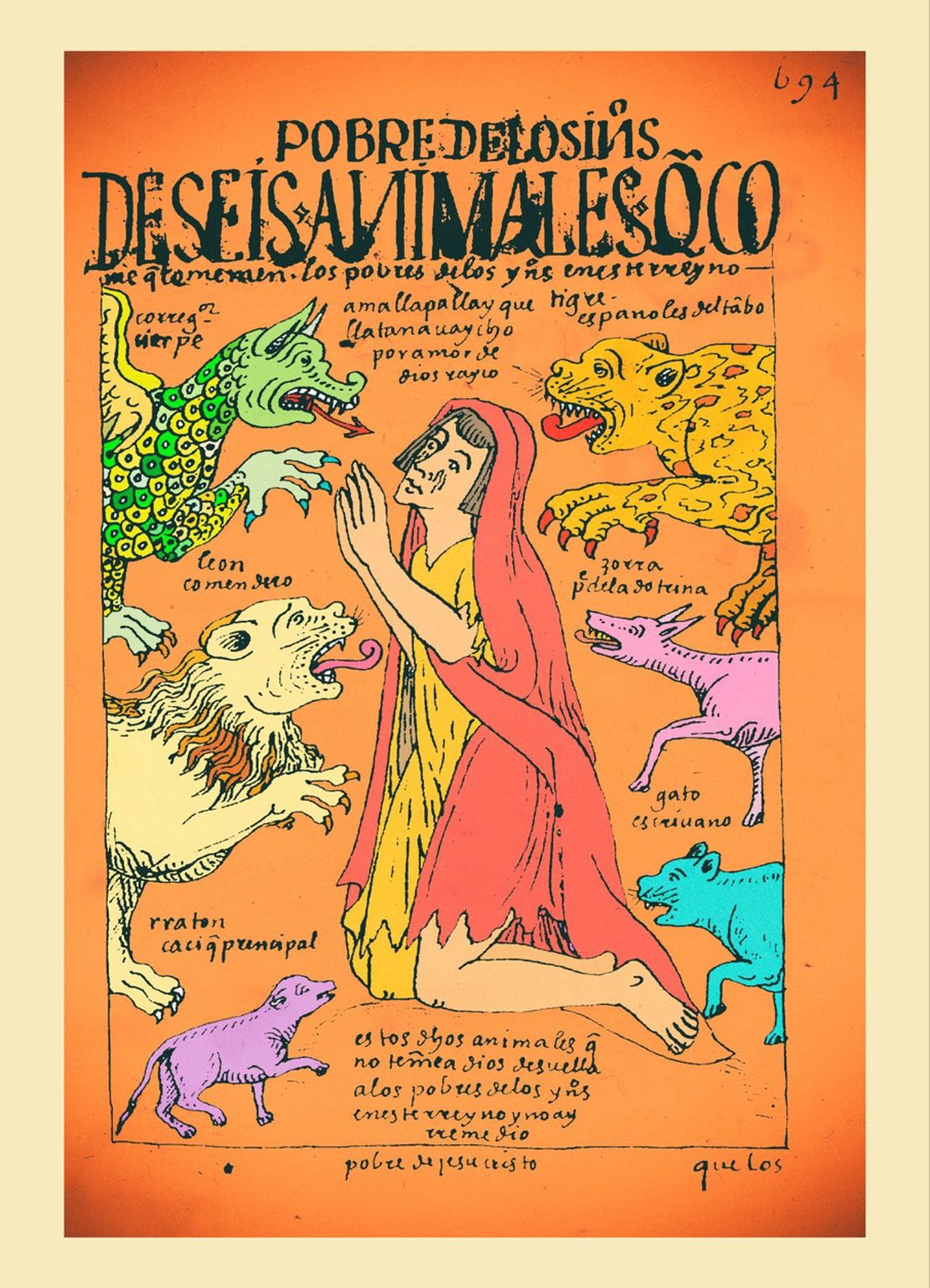

**The mita coupled with the ‘Indian’ tribute signified a heavy burden on the indigenous population. With time, mitayos decided not to return to their native land as a strategy for avoiding the mita draft and the tribute – some of them retiring to as far as Arica (now Chile). By the 17th century, many towns in the Pakaxa territory such as San Andrés de Machaqa, Julluma, Waqi, Tiwanaku, and Santiago de Machaqa were literally abandoned. In Jesús de Machaqa, as elsewhere, this process created a series of conflicting situations between the tributary population, their ethnic authorities, and the colonial authorities. By the 18th century, besides the tribute and the mita, indigenous peoples were forced to buy commodities under what became known as “repartos” . Whether they needed or wanted these products, indigenous had to buy clothings, livestock, wine etc at prices fixed by the colonial authorities. This abuse was one of the main catalysts of the Amaru and Katari 1780s rebellions in which the Pakaxa participated actively.4

REFERENCES:

Choque, Roberto, Jesús de Machaca: La Marka Rebelde. 2nd ed., vol 1. La Paz: CIPCA, 2003.

Morrone, Ariel. “Tras los Pasos del Mitayo: La Sacralización del Espacio en los ‘

Corregimientos de Pacajes y Omasuyos (1570-1650).” Boletín del Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, 44, no. 1 (April 2015): 91-116.

Morrone, Ariel .“No Todos los Caciques fueron Mallku: Mediación Política Truncada en

los Corregimientos de Pacajes y Omasuyos (Audiencia de Charcas 1570 - 1630).” Diálogo Andino 50 (June 2016): 207-217.

Pärsinnen, Martti. Caquiaviri y la Provincia Pacasa. Desde el Alto-Formativo

hasta la Conquista Española. Lima: Producciones CIMA.

Ariel Morrone, “No Todos los Caciques fueron Mallku: Mediación Política Truncada en los Corregimientos de Pacajes y Omasuyos (Audiencia de Charcas 1570 - 1630),” Diálogo Andino 50 (June 2016), 207-217. ↩︎

Ariel Morrone, “Tras los Pasos del Mitayo: la Sacralización del Espacio en los Corregimientos de Pacajes y Omasuyos (1570-1650),” Boletín del Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, 44, no. 1 (April 2015): 91-116. ↩︎

Morrone, “Tras los Pasos del Mitayo: la Sacralización del Espacio en los Corregimientos de Pacajes y Omasuyos (1570-1650)”, 96. ↩︎

Choque, Jesús de Machaca: La Marka Rebelde, 174. ↩︎