Abstract

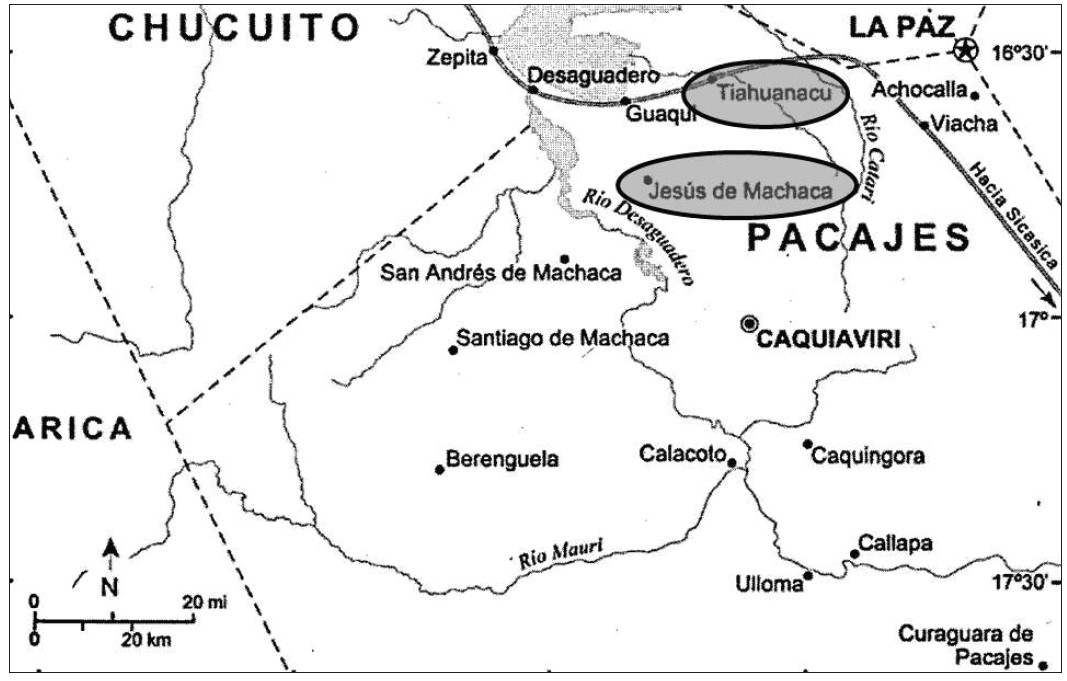

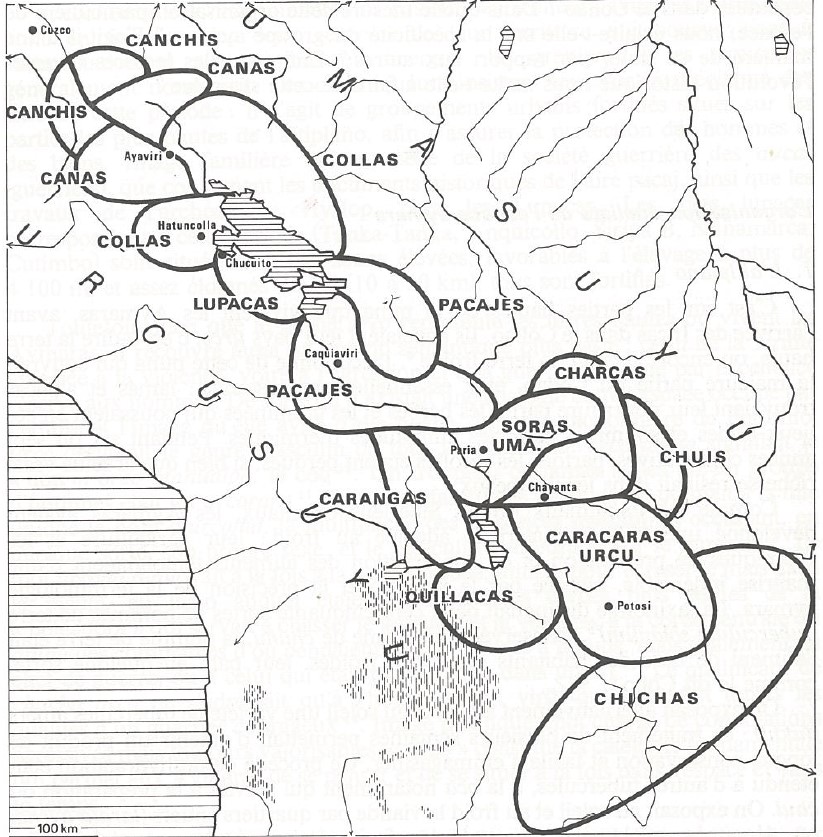

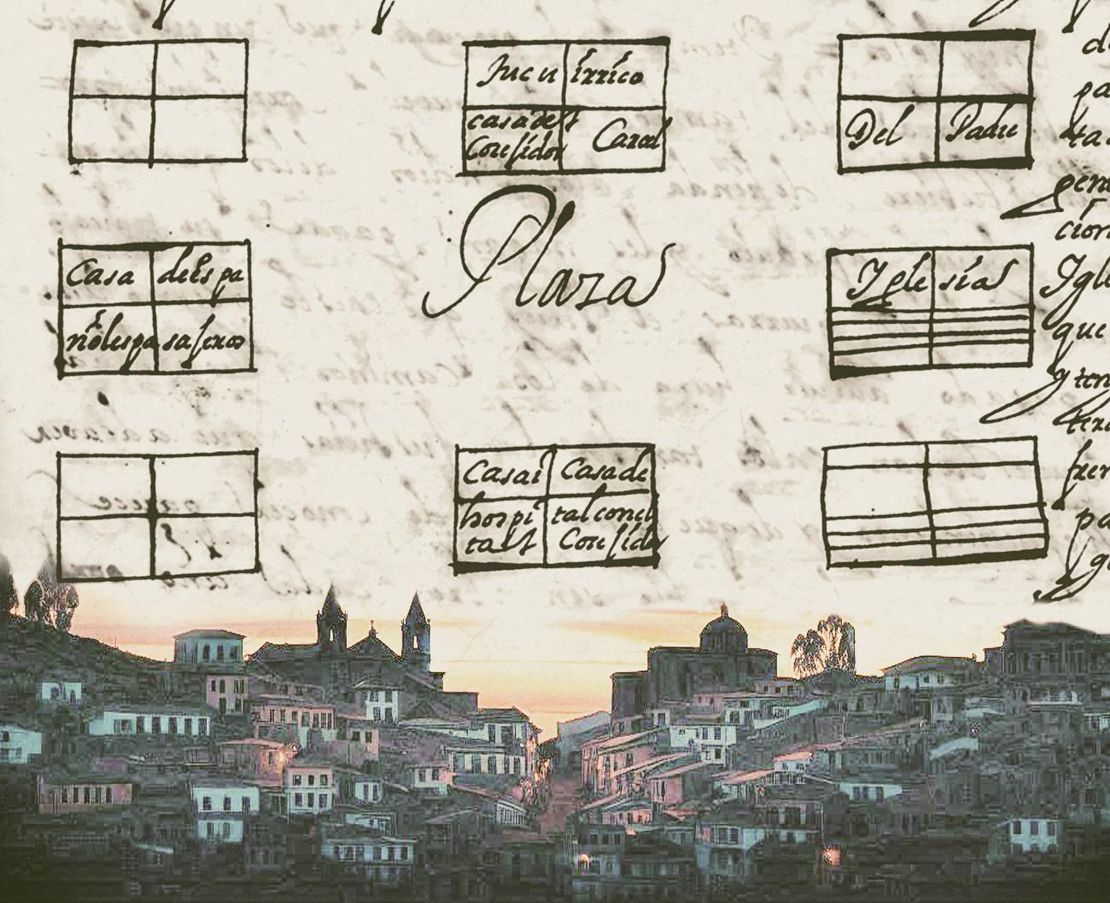

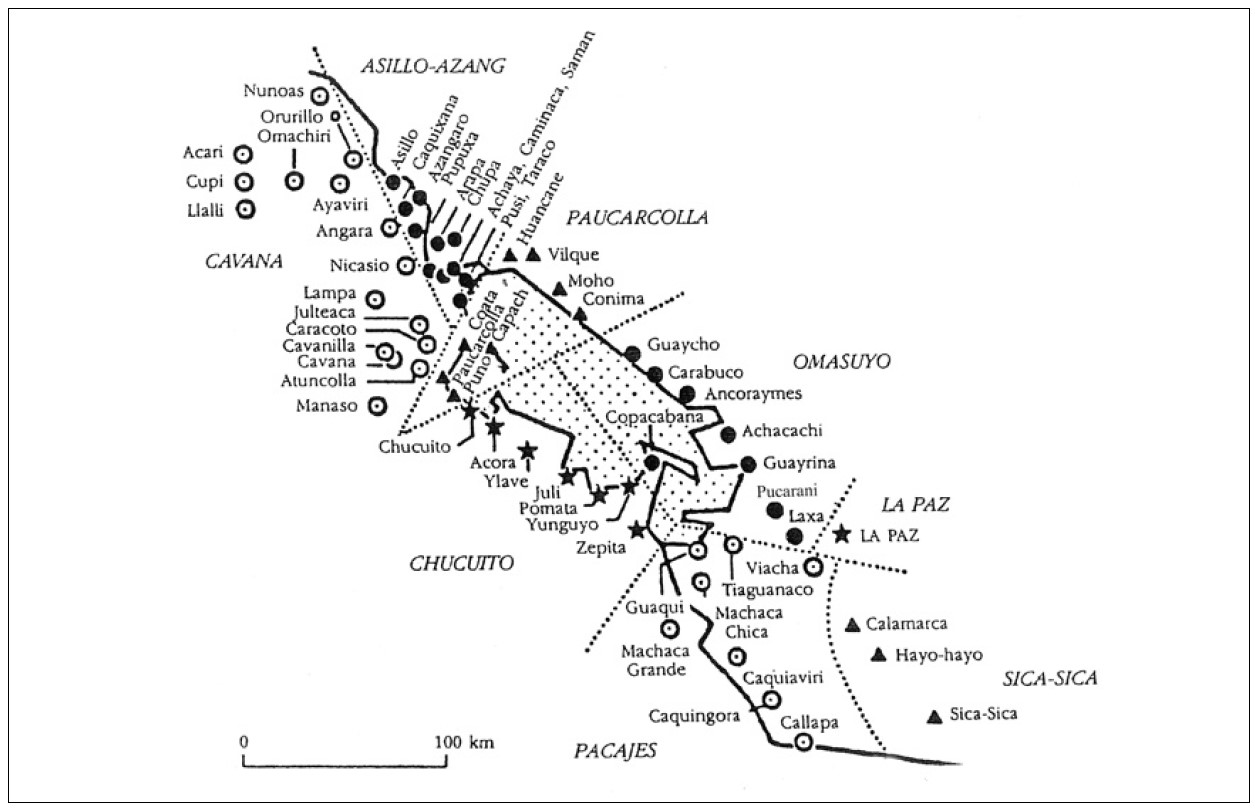

This map shows the nucleated ‘Indian Royal Towns’ established by the Spanish colonial state, through a massive forced resettlement program, in a portion of the territory of the Aymara polity of the Pakaxa (Paka Jaqi or Pacajes) located on the high plateau near the southern tip of the Titicaca lake (in present day Bolivia).1 Before Spanish colonization, this area was part of the Qullasuyu, the southern district of the Inca state or Tawantinsuyu and it was the area in which the core settlements of the large Aymara polity AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY of the Pakaxa were located (upper moiety or Urqu Pakaxa). Under Spanish colonial rule, the Qullasuyu became the southern district of the Viceroyalty of Peru called Distrito de la Audiencia de Charcas or La Plata divided into two large provinces, Charcas and La Paz. The area on the map was part of the latter which was further divided into smaller territorial administrative units. The territorial units (sort of rural districts) assigned to the indigenous population were called Corregimientos de Indios. The area shown on the map became the Corregimiento of Pacajes and encompassed a number of ‘Indian Royal Towns’ also called reducciones.

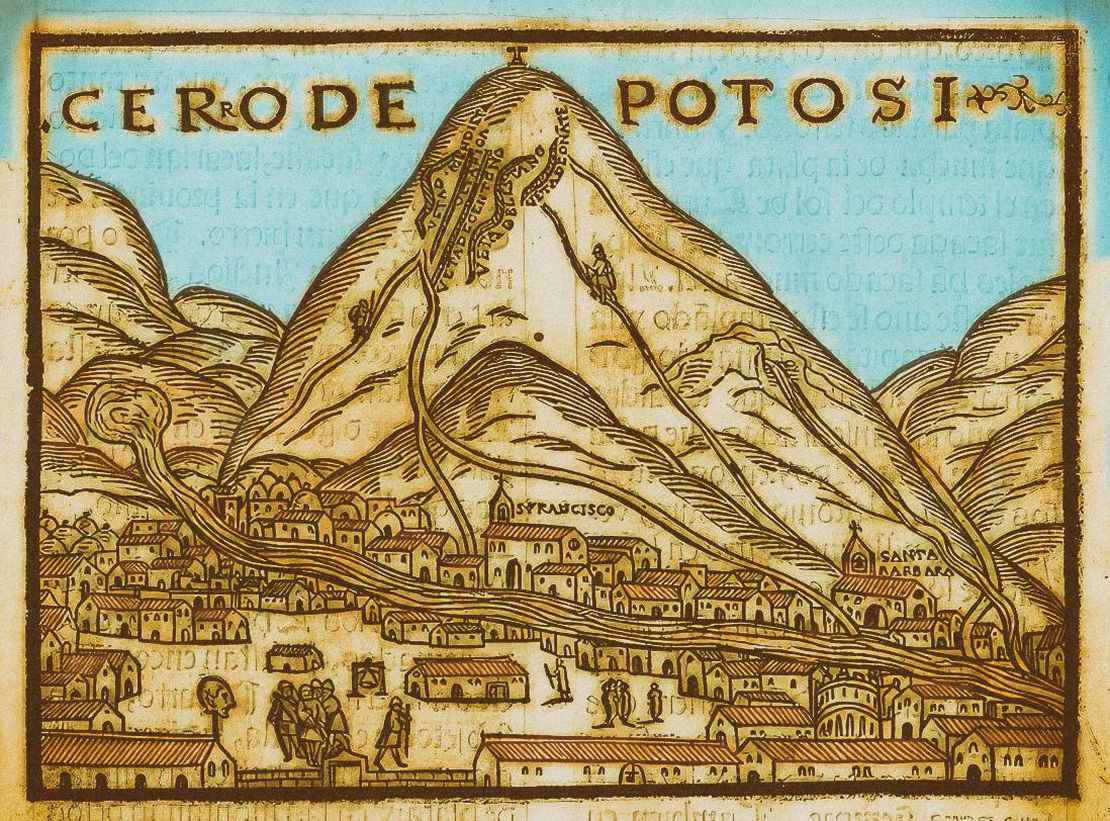

Spanish conquerors arrived into the region of the Qullasuyu in the late 1530s, but it is only in the 1570s that the Spanish crown was able to implement major transformations in order to institutionalize the presence of the Spanish colonial state in the region, consolidate its role as agent of metropolitan interests and revitalize the production of silver in the mines of Potosi. These transformations included the enforcement of a new political administrative organization of the territory of the viceroyalty, the monetization of indigenous tribute, the institutionalization of a system of indigenous draft labor,mita , and an ambitious program of forced resettlement of dispersed indigenous hamlets into fixed concentrated towns where the indigenous population could be managed, evangelized and taxed more efficiently.

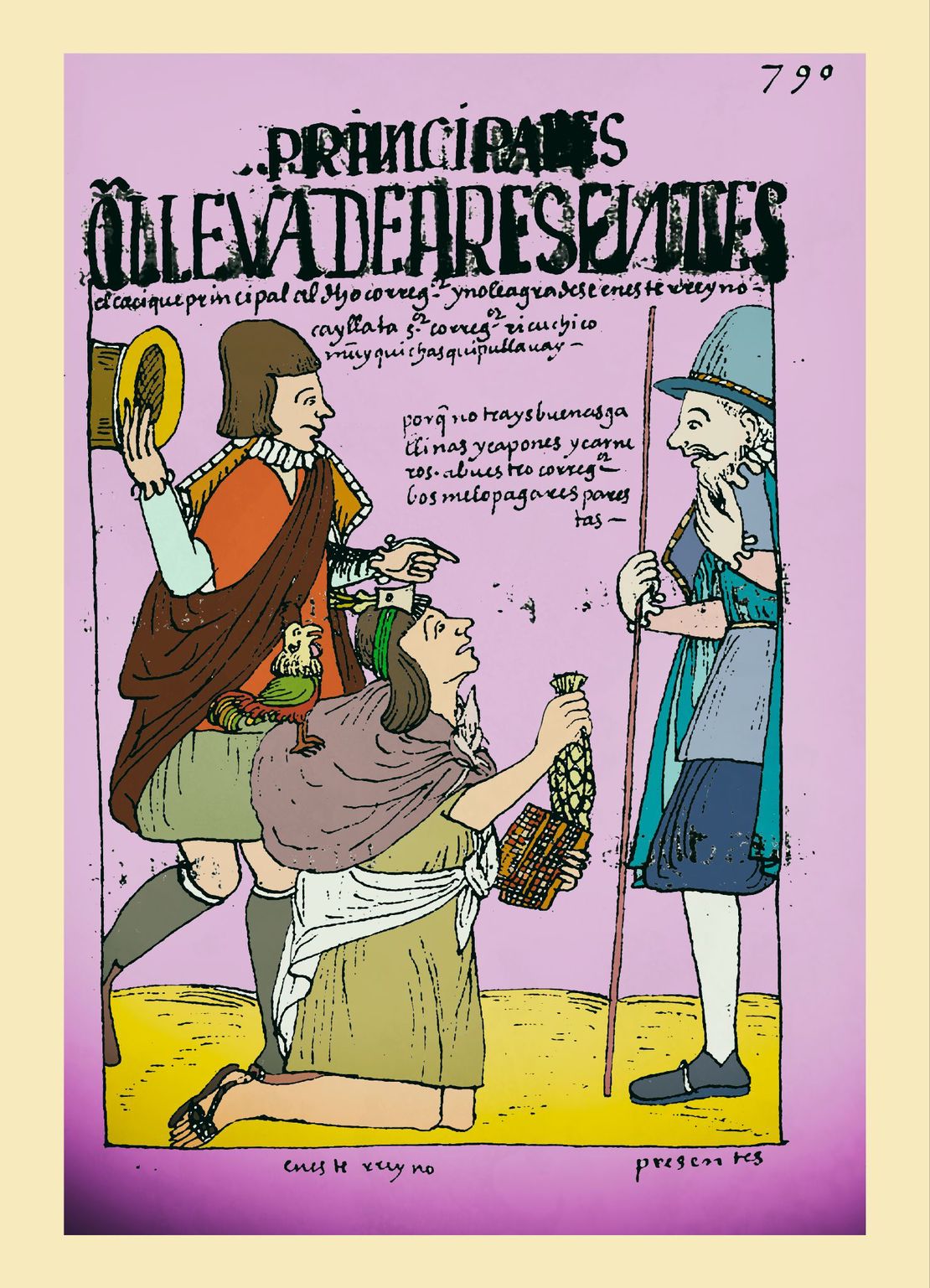

In these so called Indian Royal Towns or ‘reducciones’ ethnic authorities were to become state paid functionaries in charge of collecting tribute and delivering levied labor under the close supervision of parish priests, and other colonial officials. Dismantling what was left from pre-Columbian ethnic territories and stripping the Aymara polities from their traditional land rights, Spanish colonial officials drove people away from their ancient lands and often joined them with members of different polities. This process entailed the disarticulation of the large macro-ethnic Aymara polities, their fragmentation into smaller ‘Indian communities’ and a thorough reconfiguration of ethnic identities and claims. The memory of belonging to the larger Aymara polities faded away and the reconstituted communities within the Indian royal towns eventually became the main identity reference.

This map in particular, shows the space and forced resettlement programs experienced by the Pakaxa who occupied a large territory south of Lake Titicaca, reaching from far beyond the present borders of present-day Bolivia with Peru and Chile in the west and into the warm valleys of the Yungas in the east. The Pakaxa had land under the system of ‘vertical control of ecological tiers’ AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY both to the west in the coasts of Arica (now Chile) and Arequipa (now Perú) and to the east in the Cochabamba and Cauari valleys (now Bolivia).

No different than the other aymara polities of the high plateau, the Pakaxa had been incorporated into the Inca state but still managed to maintain some of their autonomy. The resistance offered by the Pakaxa, however, forced the Incas to carry on with a population rearrangement strategy. Having founded a “new town” after destroying Wankani (which was a sacred temple found in the Pakaxa’s main marka, the Incas transferred trusted families as mitmaqkuna (that is, as settlers), so that they would live with other less trusted families. In this way, “these two groups would have been organized into two partialities: those from mitmaqkuna as Ayllu Hurinsaya and those natives from the place as Ayllu Hanansaya.”2 This marks the beginning of what later became the Machaqa la Chica and Machaqa la Grande - to this day (albeit many changes) the strongholds of the Pakaxa.

In the context of the 1570s Toledan reforms aimed at consolidating and institutionalizing the colonial state, the Pakaxa, like the other Aymara polities AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY were submitted to the organization of reducciones, i.e., the process of forced resettlement of dispersed hamlets into nucleated ‘Indian Royal Towns’, as explained above. Specifically, as a consequence of the Toledo reduction scheme, the old space and new colonial province of Pacajes ‘INDIAN ROYAL TOWNS’ (REDUCCIONES) AND PROVINCES (CORREGIMIENTOS) UNDER SPANISH COLONIAL RULE IN THE LATE 16TH CENTURY was structured around the following eight rural districts (repartimientos) and towns: Callapa (Qallapa), Machaca (Machaqa) la Grande or Hurinsaya (later San Andrés de Machaqa), Machaca (Machaqa) la Chica or Hanansaya (later Jesús de Machaqa), Caquiaviri (Qaqayawiri o Axawiri), Viacha (Wiyacha), Guaqui (Waqi), Tiahuanaco (Tiwanaku) and Cauingora (Qaqinkura)3.This was a violent and disintegrating measure against the political and social unity of the large Aymara polities and their territorial organization. 4 What is more, from early on the potential importance of the three Machaqa and the significant agricultural and mineralogical resources (e.g. Beringela) found in the province of Pacajes gave rise to considerable increase in the amount of tribute COLONIAL LEGISLATION AS THE FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE INDIGENOUS TRIBUTE 1570s -1620s to be applied there.

Toledo also implemented the draft labor system COLONIAL LEGISLATIONS AS A FRAMEWORK FOR DISPOSSESSIONS IN THE CENTRAL ANDES: THE COLONIAL MITA known as the mita to lower the cost of indigenous labor in the mines of Potosí whose recovery was of utmost importance to the colonial state. As happened elsewhere, the mita coupled with the tribute signified a heavy burden on the indigenous population. With time, mitayos (mita workers) decided not to return to their native land as a strategy for avoiding the mita draft and the tribute – some of them retiring to as far as Arica. By the 17th century, many towns such as San Andrés de Machaqa, Julluma, Waqi, Tiwanaku, and Santiago de Machaqa were literally abandoned. In Jesús de Machaqa, as elsewhere, this process created a series of conflicting situations between the tributary population, their indigenous authorities and the colonial authorities.5

By the 18th century, the tribute and the mita, indigenous peoples were forced to buy commodities under what became known as “repartos”. Whether they needed or wanted these products, indigenous had to buy clothings, livestock, wine etc. at prices fixed by the colonial authorities (corregidores). This abuse was one of the main catalysts of the Amaru and Katari 1780s rebellions in which the Pakaxa participated actively.6

After independence and the creation of the Republic of Bolivia in the early 19th century, the country underwent a transformation where colonial tributes evolved into direct contributions tied to land and rent. This shift deepened the breakdown of traditional ayllu and communal lands, converting them into private property. While in practice this process took some time to be fully implemented and communities managed to maintain their traditional structure for some additional time, when the 1874 Ley de Ex-vinculación was passed the real process of land expropriation took place. Indeed, this law canceled all forms of collective or communal property and imposed individual private property as the only legally sanctioned form of property. The brutal enforcement of this law, meant the territorial dispossession of indigenous communities and the significant expansion of privately owned large estates (latifundio) benefitting “progressive” landowners.7

However, they faced fierce resistance in Machaqa where the indigenous communities (ayllus) managed to put together their collective titles as a testimony of their ancestral occupation of the territory.8 In October of 1870 a Supreme Resolution was passed by the government that declared the ‘Indians’ of Jesús de Machaqa as legitimate owners of their ancestral lands. Ever since, this has been the legal basis upon which the 12 ayllus of Jesús de Machaqa continued to defend their lands which were later officially titled by the National Institute of Agrarian Reform during the 1953 agrarian reform. Despite initial resistance and legal victories securing land rights in places like Jesús de Machaqa, these victories did not signify the end of the battles against the oppression they encountered daily. In 1921, there was an uprising in Jesus de Machaqa where “given their desperate reality, the indians who no longer wanted to endure the hateful oppression of their corregidor and not having found justice or some kind of protection, decided to physically get rid of the corregidor”9 This uprising was violently repressed by the government who sent military troops in what has been one of the bloodiest repressions and massacres documented in the contemporary history of the Bolivian indigenous people.10

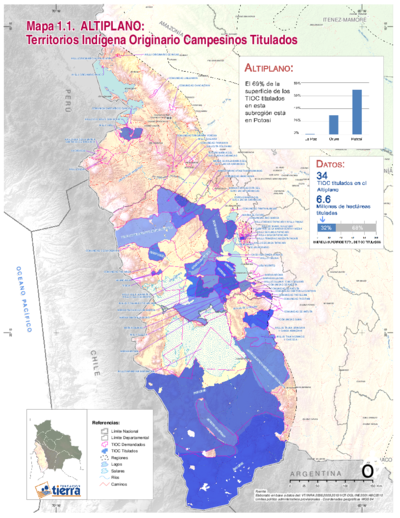

In the late 20th century, Bolivia witnessed a resurgence of indigenous identity and territorial claims, including the reconstitution of ayllus under the concept of a Pakajaqi nation in the Pacajes / Pakaxa case. This movement aimed to reclaim ancestral territories and cultural heritage, supported by organizations like CONAMAQ (Consejo Nacional de Markas y Ayllus del Qullasuyu). Efforts included seeking recognition as Territorios Indígenas Originario Campesinos (TIOCs) to formalize communal land titles, although the process faced bureaucratic challenges and internal divisions among community members; this denomination aims to acknowledge the names different indigenous peoples use to identify themselves.

Presently, the Pacajes territory encompasses multiple TIOCs, totaling approximately 200,000 hectares across La Paz and Potosí departments. This ongoing struggle reflects a broader indigenous movement in Bolivia striving for territorial autonomy, cultural preservation, and social justice in the face of historical and contemporary challenges.

REFERENCES:

Andrade, Norby Margoth. “La Mita en los Andes Bolivianos de la Provincia

Colonial de Omasuyos en el Siglo XVII.” Estudios Latinoamericanos 1 (2017):

28-33.

Choque, Roberto. Jesús de Machaca: La Marka Rebelde. 2nd ed., vol 1. La Paz:

CIPCA, 2003.

Choque, Roberto and Esteban Ticona. Jesús de Machaca: La Marka Rebelde. 1st ed,

vol. 2. La Paz: CIPCA, 1996.

Morrone, Ariel. “No Todos los Caciques Fueron Mallku: Mediación Política Truncada

en los Corregimientos de Pacajes y Omasuyos (Audiencia de Charcas 1570 -

1630).” Diálogo Andino, no.50 (June 2016): 207-217.

Ariel Morrone, “No Todos los Caciques fueron Mallku: Mediación Política Truncada en los Corregimientos de Pacajes y Omasuyos (Audiencia de Charcas 1570 - 1630),” Diálogo Andino 50 (June 2016), 207-217. ↩︎

Roberto Choque, *Jesús de Machaca: la Marka Rebelde (*La Paz: CIPCA, 2003), 31. ↩︎

Choque, Jesús de Machaca: la Marka Rebelde, 35. ↩︎

Norby Andrade, “La Mita en los Andes Bolivianos de la Provincia Colonial de Omasuyos en el Siglo XVII. Estudios Latinoamericanos 1 (2017), 30. ↩︎

Choque, Jesús de Machaca: la Marka Rebelde, 21. ↩︎

Choque, Jesús de Machaca: la Marka Rebelde, 174. ↩︎

Choque, Jesús de Machaca: la Marka Rebelde, 269. ↩︎

Choque, Jesús de Machaca: la Marka Rebelde, 266. ↩︎

Roberto Choque and Esteban Ticona, Jesús de Machaca: la Marka Rebelde. 1st ed, vol. 2. (La Paz: CIPCA,1996), 68. ↩︎

Choque and Ticona, Jesús de Machaca: la Marka Rebelde, 68. ↩︎