Abstract

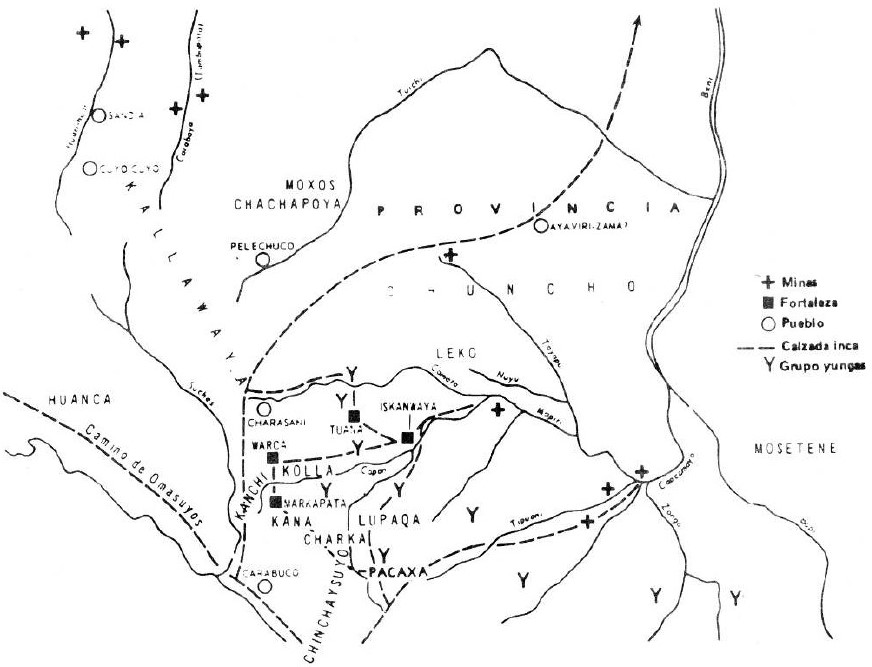

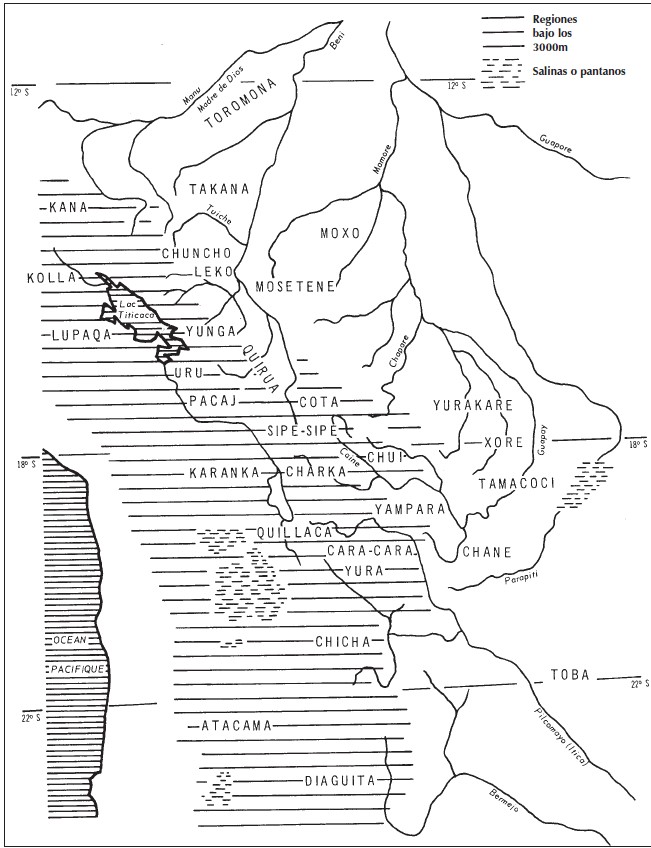

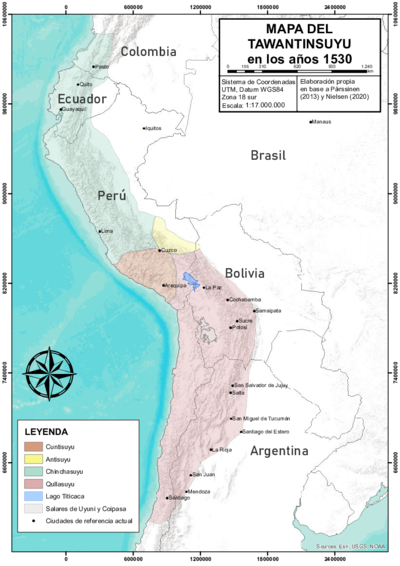

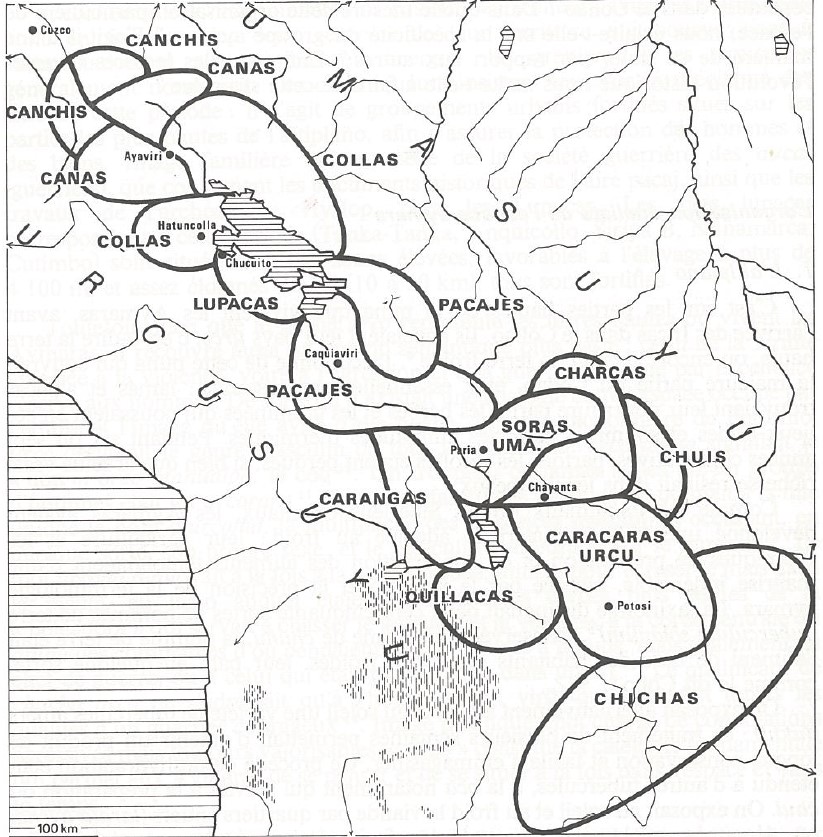

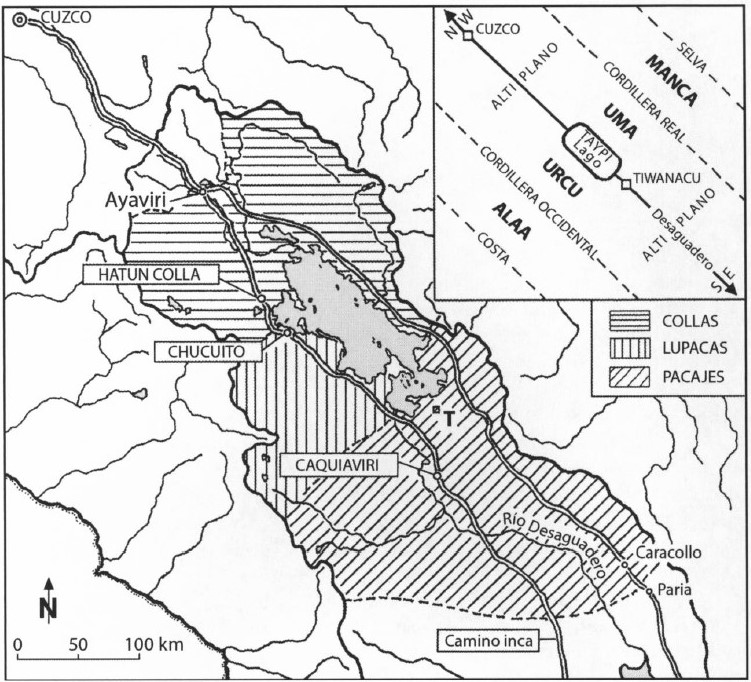

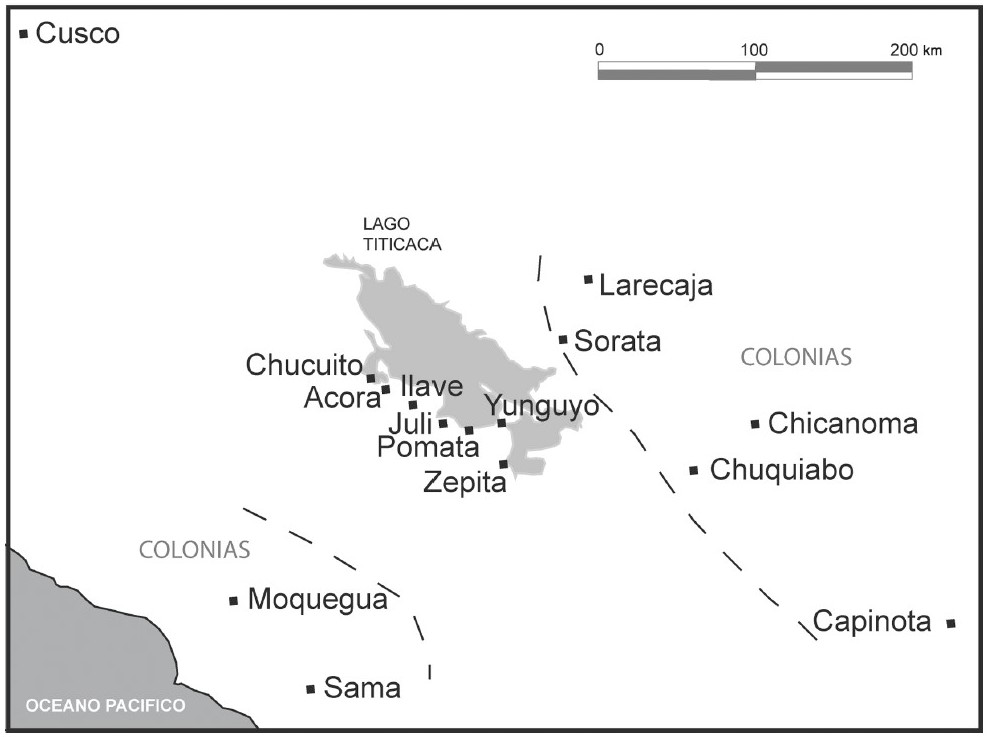

The region shown in the map, was part of theQullasuyu, which was the southern district of the Inca state, also known as the Tawantinsuyu which included the large high plateau where the Titicaca Lake is located, the inter-Andean valleys to the east, and the valleys and coastal lands to the west. This map shows the various Lupaqa islands located eastward in the valleys of Larecaja (in present-day Bolivia) in the 16th century. These islands which were intermixed with those of other Aymara Polities AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY , such as the Pakaxa ‘INDIAN ROYAL TOWNS’ (REDUCCIONES) IN THE PACAJES PROVINCE (CORREGIMIENTO) UNDER SPANISH COLONIAL RULE IN THE LATE 16TH CENTURY , Charka, Kana and Qulla, are a result of Inca state resettlement policies which were based on the ‘vertical control of ecological tiers’ system. While the core settlements of the Lupaqa were located in the cold lands of the high-plateau THE AYMARA POLITY OF THE LUPAQA: COMMERCIAL DESTINIES AND VERTICALITY IN THE 16TH CENTURY near the Titicaca Lake (the most important being Chucuito, located at the border between present-day Peru and Bolivia), their territory also included a series of “islands” at different altitudes down the western and eastern valleys thus forming a sort of ‘vertical archipelago.’1

In the process of Inca expansion southwards, Aymara polities such as the Lupaqa were initially major rivals to the Incas and were only subdued after long struggles. Once integrated into the Inca state (late 1400s) as respectful allies and warriors, they made substantial contributions to the expansion of the Inca state’s eastern and southern borders THE EASTERN BORDERS OF THE QULLASUYU - SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF THE INCA STATE - 16th CENTURY . For these contributions, Aymara polities were rewarded with grants of maize valley land, exempted from certain tribute obligations, and, more importantly, were allowed to retain a large degree of autonomy under Inca indirect rule. In these ways the Inca state consolidated the hegemony of Aymara polities and the power of their authorities over the territories they shared with the Urus, Pukinas, and other ethnic groups. The Lupaqa islands THE AYMARA POLITY OF THE LUPAQA: COMMERCIAL DESTINIES AND VERTICALITY IN THE 16TH CENTURY both to the west and the east were occupied by permanently resettled Lupaqas (called mitmaqkuna) who were sent there from the seven Lupaqa high plateau centers to produce goods (such as coca and maize) which were in turn sent back to the center within a framework of a tributary relationship.2

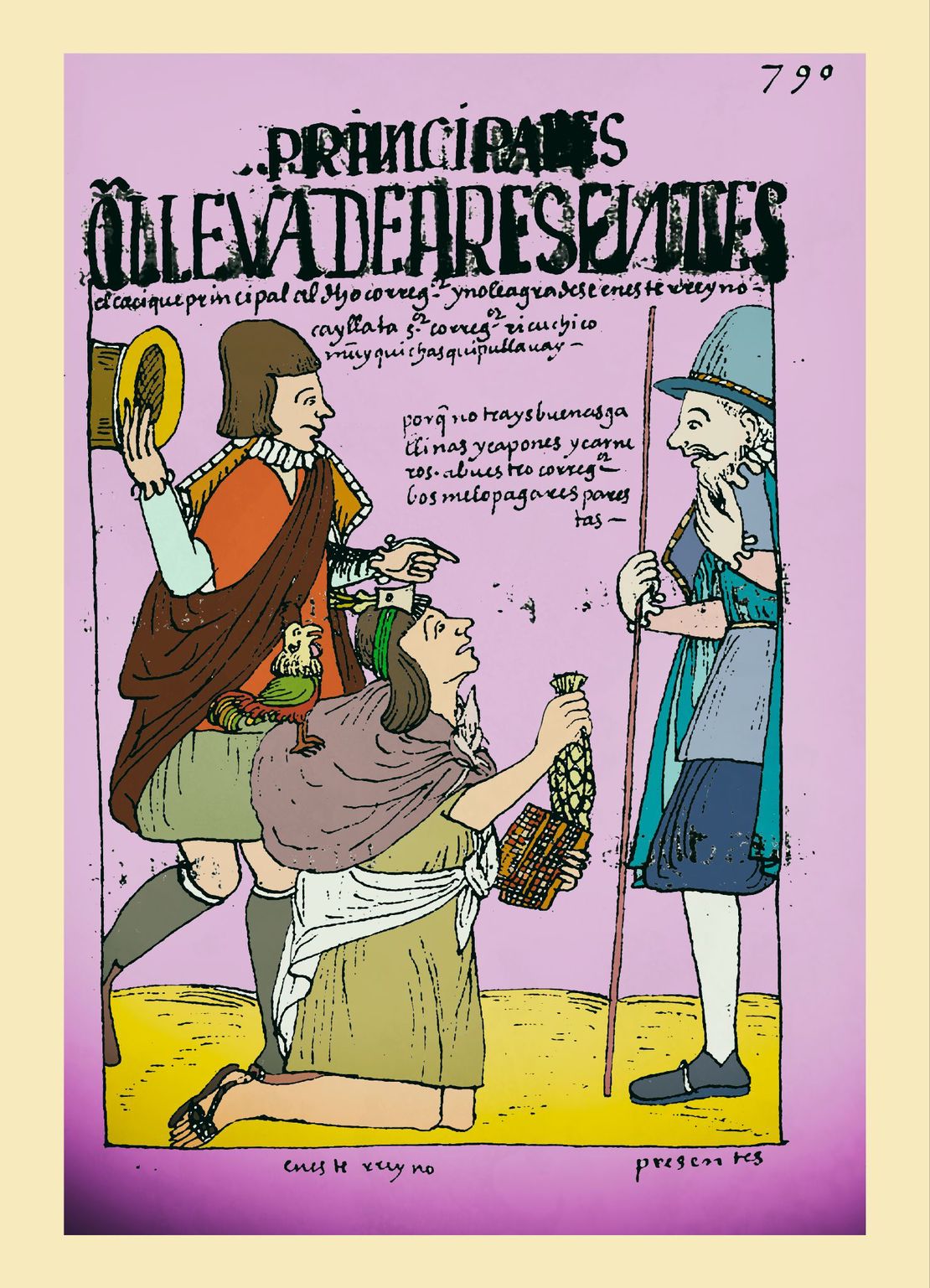

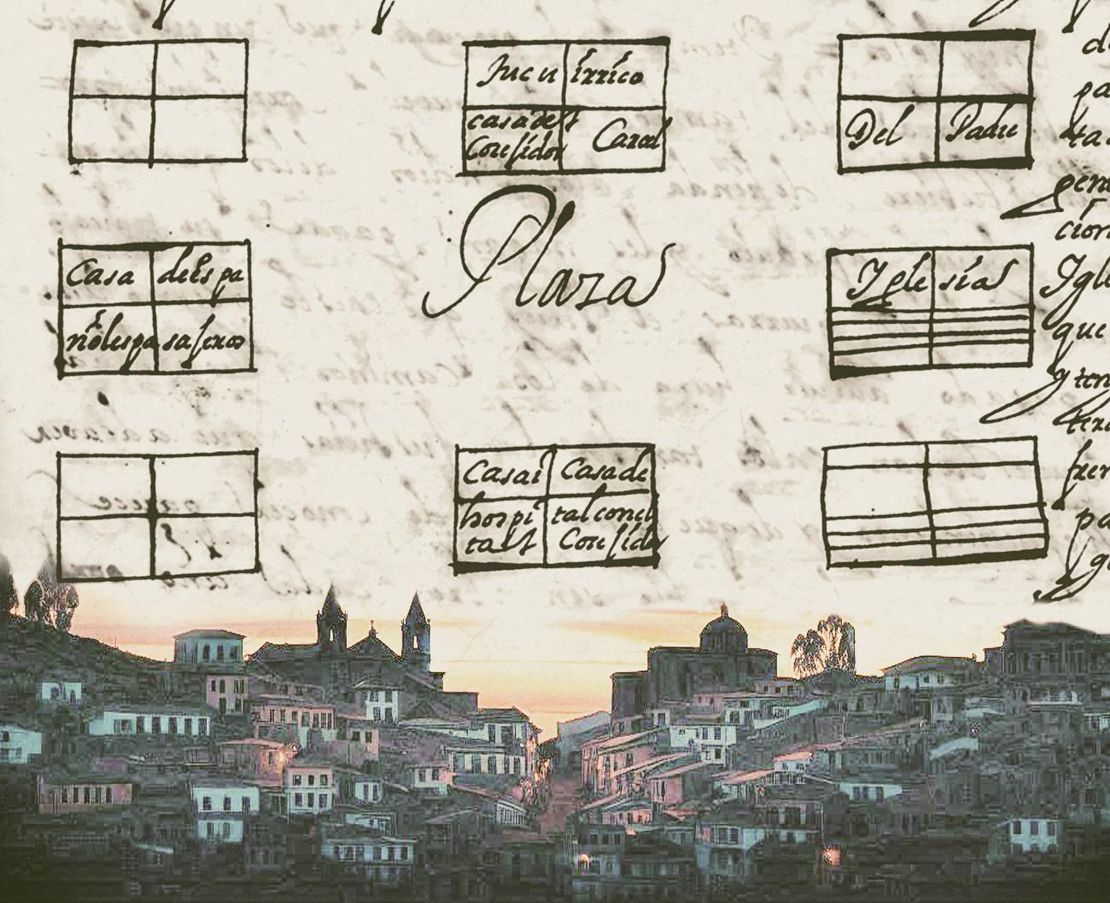

Over time, the pressures of colonial rule, including the pressures of tribute, the creation of reducciones (forced resettlements into concentrated indigenous towns designed to facilitate easier control and conversion) and the mita further eroded traditional structures and memories. **Colonial policies, aimed at integrating indigenous populations into the Spanish colonial framework, led to a gradual disarticulation and fragmentation of the large precolonial aymara polities. Nowadays, the indigenous communities residing in the former Lupaqa settlements primarily speak Aymara. However, the collective memory of having been part of a larger Lupaqa macro-ethnic polity has faded.

**

As communities adapted to new socio-political environments, the stories and traditions that once emphasized their belonging to the Lupaqa macro-ethnicity were not consistently passed down. Instead, a broader Aymara identity emerged, reflecting a more generalized cultural and linguistic heritage that is still vibrant today but no longer tied to the specific historical consciousness of the Lupaqa polity. In essence, while the language and some cultural practices have persisted, the specific ethnic identity tied to the Lupaqa macro-ethnicity has been overshadowed by the broader Aymara identity. This reflects the profound and lasting impacts of colonization and the complex processes of cultural change and resistance over the centuries.

REFERENCES:

Murra, John. “Los límites y las limitaciones del ‘archipiélago vertical’ en los Andes.” Lecture, Segundo Congreso Peruano del Hombre y la Cultura Andina, Trujillo. October, 1974.

Saignes, Thierry. Los Andes Orientales Historia de un Olvido. Cochabamba: CERES/IFEA, 1985.

Van Buren, Mary. “Rethinking the Vertical Archipelago.” American Anthropologist 98, no. 2 (June 1996): 338–51.

John Murra, “Los Límites y las Limitaciones del ‘Archipiélago Vertical’ en los Andes.” (Lecture at the Segundo Congreso Peruano del Hombre y la Cultura Andina, Trujillo, Perú, October, 1974); Mary Van Buren, “Rethinking the Vertical Archipelago.” American Anthropologist 98, no. 2 (June 1996): 338–51 ↩︎

Thierry Saignes. Los Andes Orientales Historia de un Olvido. (Cochabamba: CERES/ IFEA, 1985). ↩︎