Abstract

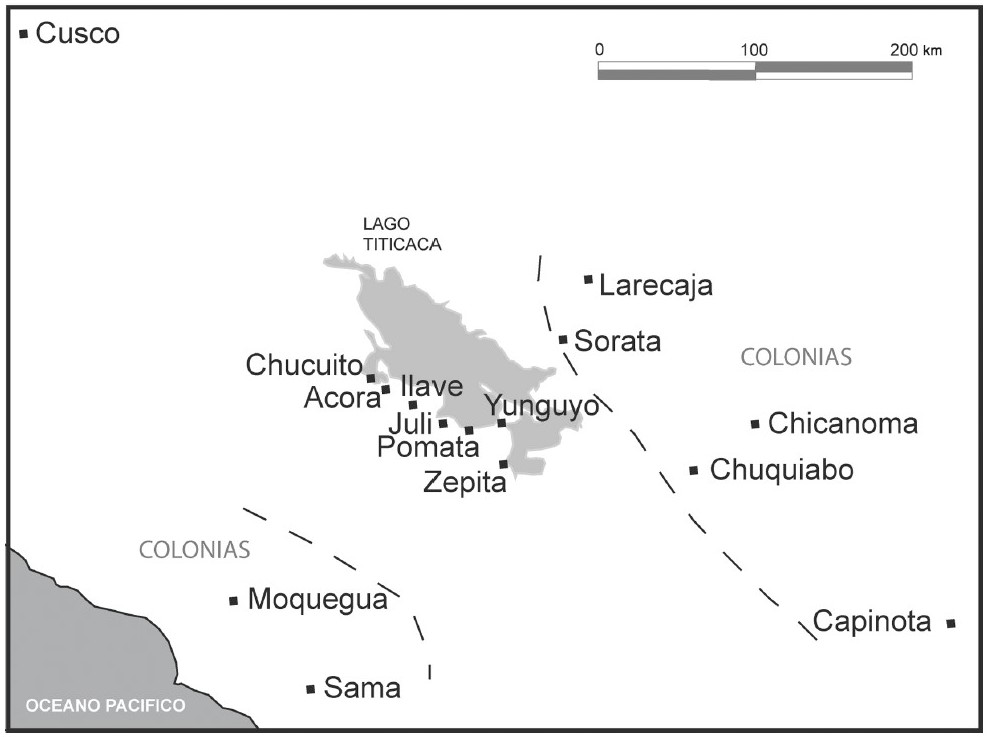

This map shows the various ‘islands’ or colonies that the Aymara polity AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY of the Lupaqa had both to the east and the west of the high plateau in the [*Qullasuyu*](/en/content/BOL0002Y/), the southern district of the Inca state or [*Tawantinsuyu*](/en/content/BOL0001Y/), in the 16th century. The map is based on the information found in the 1567 Spanish colonial census, which included testimonies from the Lupaqa authorities.[^1] Following the Andean model of ‘vertical control of ecological tiers’ AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY the core settlements of the Lupaqa were located in the cold lands of the high-plateau, but their territory included a series of “islands” at different altitudes down the western and eastern valleys thus forming a sort of ‘vertical archipelago.’[^2] As shown in the map, the core settlements were near the Titicaca Lake (the most important being Chucuito, located at the border between present-day Peru and Bolivia), two islands or colonies down the western slopes (now in Peru) and 5 down the eastern slopes (now in Bolivia).The Lupaqa polity is believed to have had a population of 20,000 households according to the last Inca khipu record or 100,000 inhabitants at the time of the Spanish Conquest – a significant population for those days and much larger than the other polities that existed contemporaneously to them.1 Much of what is known today about the Lupaqas comes from two main sources: the 1567 administrative visit carried out by Garci Diez de San Miguel and the new census carried out during Toledo’s Visita General in the 1570s.2 In 1951 Marie Helmer published a summary of the administrative visit carried out in 1567 which included the province of Chucuito, the administrative center of the Lupaqa. When the full text of the visit was published some years later a greater interest arose thanks to the detailed information it contained therefore engaging ethnologists, archeologists, ethnographers, and historians alike. 3 This text which included information on the previous censuses of 1553 and 1559 as well as the 1567 one, gained wider historical perspective when it was compared to the information of Virrey Francisco de Toledo’s rule (1569 – 1581) during which a new census was carried out during his Visita General in the 1570s.4

When the Incas reached the Titicaca Lake, the Lupaqa did not confront them in battle - unlike local groups occupying the north and eastern shores of the Lake who offered great resistance to the Inca invasion - rather, they became integrated into the Inca jurisdiction.5 This meant that, “the Lupaca kings and their governors were local Aymara-speaking individuals who were not replaced by Inca governors, as was often the case in areas that fell under Tawantinsuyu rule”6 (own translation).

What is more, the strong Inca influence on Lupaqa life suggests that the Lupaqa polity (or at least its elite) was able to flourish through this symbiotic relationship with the Inca. It is possible that the Incas reinforced the elite’s power in exchange of these people’s contribution to the state in terms of clothing and manpower – especially when the state intervened in some conquest.7 From the Lupaqa point of view, this relationship allowed them to maintain their autonomy – at least relative to that of their neighbors. This is relevant when considering that the Lupaqas were able to maintain some of this autonomy well into the colonial regime. Indeed, the Lupaqa were not forced into an encomienda but rather they became a “repartimiento real”. This means that the Crown oversaw the repartimiento directly, and therefore the tribute they had to pay as vassals of the king went directly to the Spanish crown.

The map which shows distances that took up to two months to be traveled, is a testament of the Lupaqas prestige as herders and long-distance carriers. This proved expertise ultimately also gave them leverage and a privileged position when negotiating terms with both the Inca state and the subsequent Spanish colonial administration, therefore maintaining a level of autonomy, unlike other polities who might have been less influential.

It is also important to note that given their significant agricultural surplus, the Lupaqa valley ‘islands’ played a crucial role in supplying goods to Spanish colonizers, providing Spanish cities with wine, wheat, maize, and coca during the second half of the 16th century.8 This economic utility afforded the Lupaqas a different form of dispossession, where they were integrated into the colonial economy rather than being outrightly displaced or subjected to the same degree of exploitation as other groups. What is more, this agricultural output helped sustain Spanish cities and settlements, facilitating the growth and consolidation of colonial power in the region.

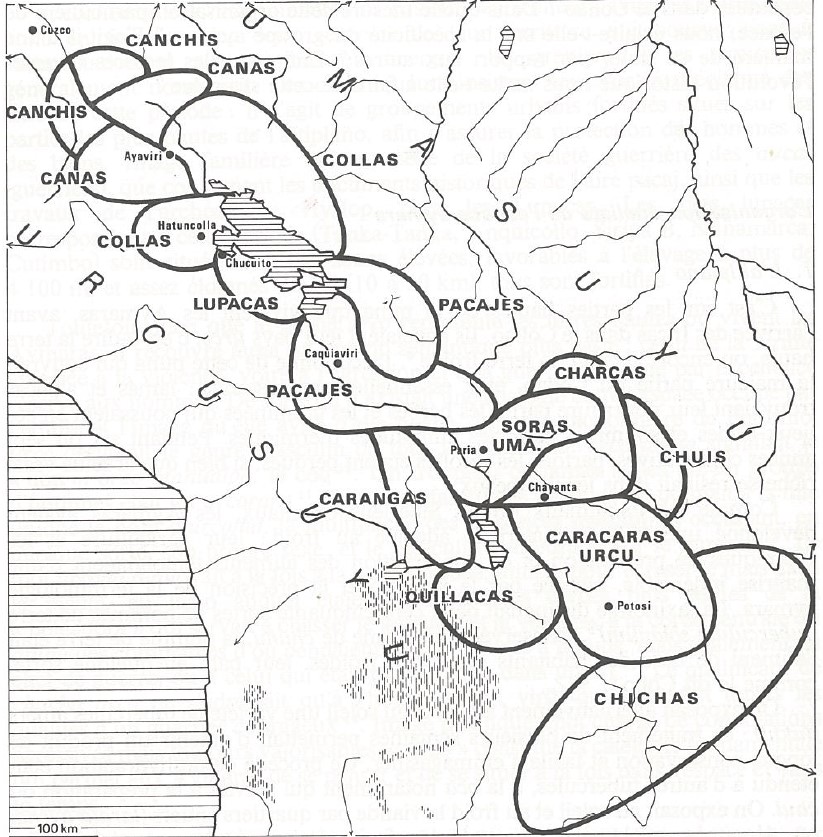

Altogether, this illustrates how the colonization experience, and therefore the varying forms of dispossession experienced, was unique to each Aymara polity AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY . Each group’s pre-colonial social structure, economic activities, geographical location, and relationship with the Inca state influenced how they were affected by and responded to Spanish colonization.

REFERENCES:

Choquecahua, Alex. “Caciques del Reino Lupaca en la Provincia de Chucuito de la

Intendencia de Puno - 1786 – 1824”. Revista Peruana de Antropología 5, no. 6 (2020): 159-164.

Cook, Noble David (Ed.). Tasa de Visita General de Francisco de Toledo. Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 1975.

Diez de San Miguel, Garci. Visita Hecha a la Provincia de Chucuito por Garci Diez de San Miguel en el Año 1567. Lima: Casa de la Cultura Peruana, 1964.

Gallardo Ibáñez, Francisco. “Sobre El Comercio y Mercado Tradicional Entre Los Lupaca Del Siglo XVI: Un Enfoque Económico Sustantivo.” Chungará 45, no. 4 (2013): 599–612.

Hyslop, John. “El Área Lupaca bajo el Dominio Incaico: un Reconocimiento Arqueológico”. Histórica 3, No.1, (1979): 53-79.

Julien, Catherine. Toledo y los Lupacas: Las Tasas de 1574 y 1579. Herausgeber, 1998.

Murra, John. “An Aymara Kingdom in 1567”. Ethnohistory 15, no. 2 (1968): 115-151.

Murra, John. “Los Límites y las Limitaciones del ‘Archipiélago Vertical’ en los Andes.” Lecture, Segundo Congreso Peruano del Hombre y la Cultura Andina, Trujillo, Perú, October, 1974.

Van Buren, Mary. “Rethinking the Vertical Archipelago.” American Anthropologist 98, no. 2 (June 1996): 338–51.

John. Hyslop, “El Área Lupaca bajo el Dominio Incaico: un Reconocimiento Arqueológico” Histórica 3, no.1 (1979): 53-79; Van Buren, “Rethinking the Vertical Archipelago.”, 338–51.; John Murra, “An Aymara Kingdom in 1567”. Ethnohistory 15, no. 2 (1968): 115-151; Alex Choquecahua, “Caciques del Reino Lupaca en la Provincia de Chucuito de la Intendencia de Puno - 1786 – 1824”. Revista Peruana de Antropología 5, no. 6 (2020). ↩︎

Noble David. Cook, (Ed.). Tasa de Visita General de Francisco de Toledo (Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 1975); Garci Diez de San Miguel, Visita Hecha a la Provincia de Chucuito por Garci Diez de San Miguel en el año 1567. (Lima: Casa de la Cultura Peruana, 1964). ↩︎

Diez de San Miguel, Visita hecha a la Provincia de Chucuito por Garci Diez de San Miguel en el año 1567. ↩︎

Catherine Julien, Toledo y los Lupacas: Las Tasas de 1574 y 1579. (Herausgeber, 1998). ↩︎

Choquecahua, “Caciques del Reino Lupaca en la Provincia de Chucuito de la Intendencia de Puno - 1786 – 1824,” 159-164; Hyslop, “El área Lupaca bajo el Dominio Incaico: un Reconocimiento Arqueológico,”,53-79. ↩︎

Hyslop, “El Área Lupaca bajo el Dominio Incaico: un Reconocimiento Arqueológico,” 55. ↩︎

Hyslop, “El Área Lupaca bajo el Dominio Incaico: un Reconocimiento Arqueológico,” 55. ↩︎

Gallardo Ibáñez, “Sobre El Comercio y Mercado Tradicional Entre Los Lupaca Del Siglo XVI: Un Enfoque Económico Sustantivo,” 341. ↩︎