Abstract

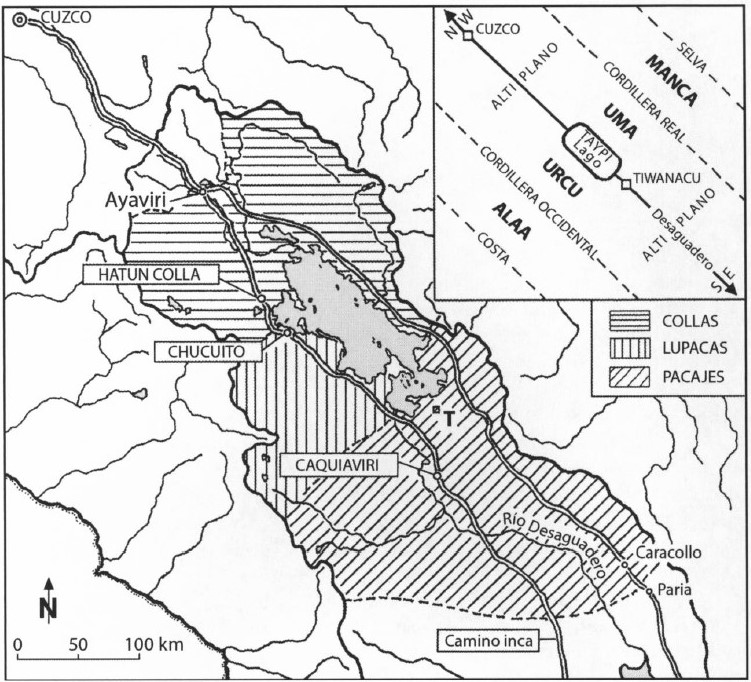

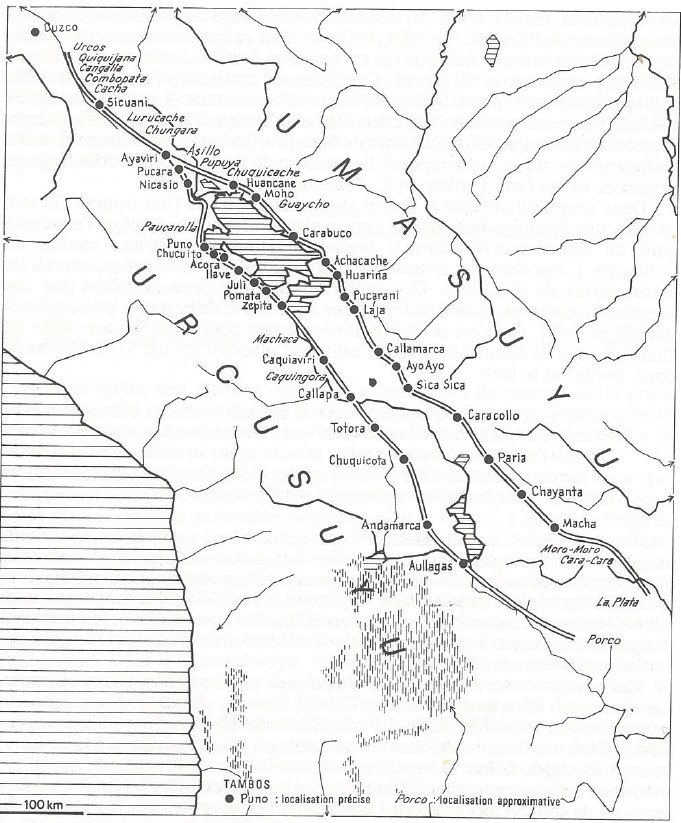

This map shows the Aymara polities AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY of the Qullas, Lupaqas, and Pakaxa (Collas, Lupacas, and Pacajes) that inhabited an area of the Qullasuyu, the southern district of the Inca state or Tawantinsuyu, in the 15th and 16th centuries. The map is based on a 1585 colonial document in which the author, a Potosi mine owner, listed the tributary units established by the colonial state in the context of major reforms implemented by Viceroy Toledo in the 1570s.1 The map also shows the major Inca Road INCA ROADS AND TAMBOS in the 16th CENTURY , with the administrative centers of Ayaviri and Hatun Colla (Qulla territory), Chucuito (Lupaqa territory), and Caquiaviri (Pakaxa territory).

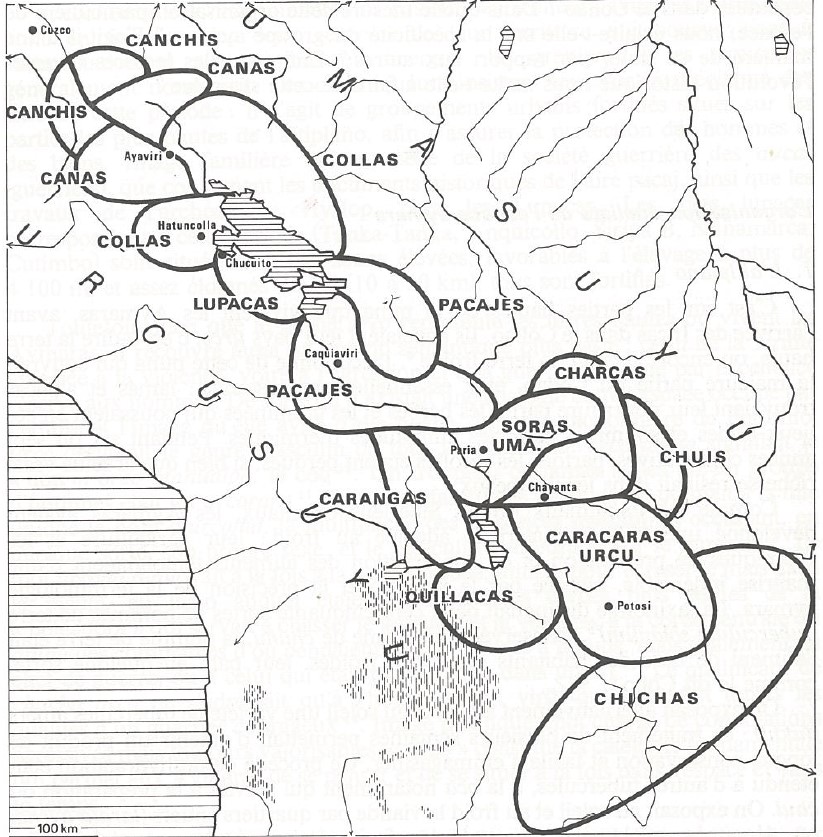

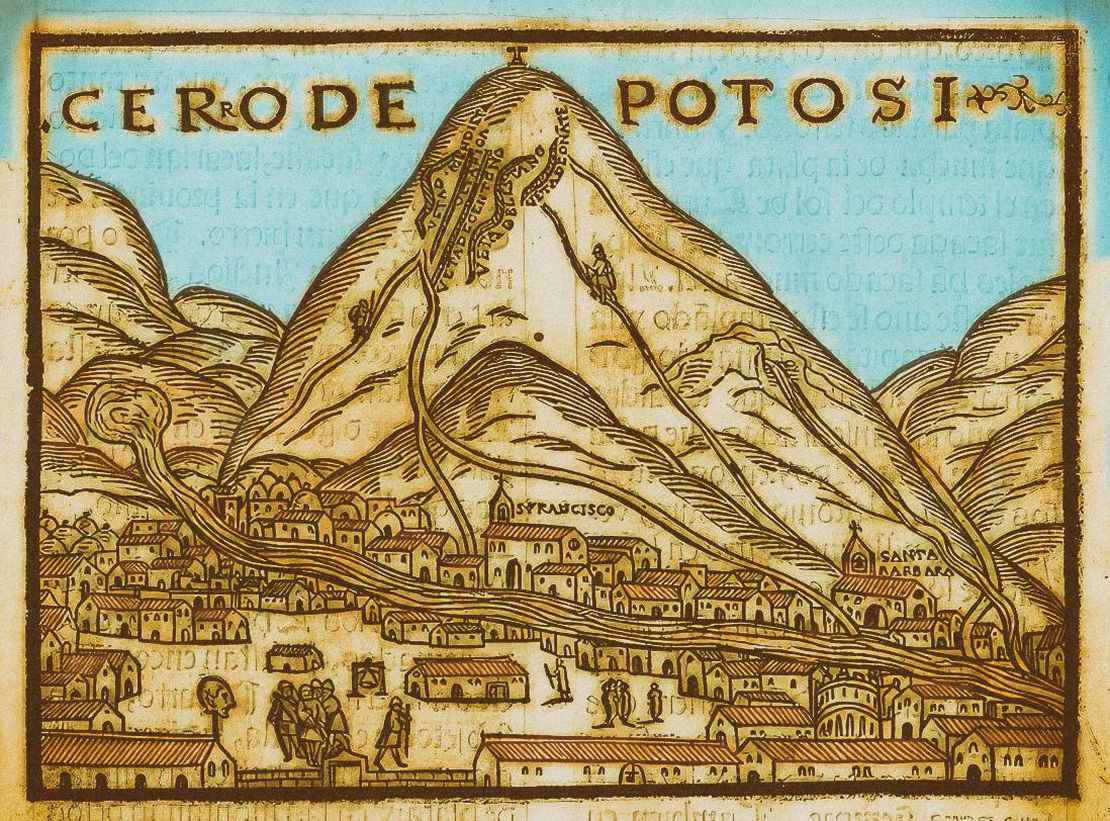

Called capitanias de mita (mita captaincies), the tributary units implemented in the second half of the 16th century were a colonial institution created to more effectively organize and manage the rotating draft labor system (called mita) for the Potosi silver mines.2 These units helped in coordinating the recruitment, transportation, and supervision of indigenous laborers. In each captaincy, the indigenous draft laborers, able men ages 18-50, were under the control of an ethnic leader, the “mita captain”, whose area of authority and jurisdiction roughly corresponded to that of a pre-Hispanic “macroethnic” Aymara polity.3

The mita system imposed quotas on different indigenous communities, requiring them to provide a certain number of laborers for specific periods. Mita captaincies facilitated the enforcement of these quotas by recruiting the labor force within their jurisdiction. This often involved coercion, as indigenous people were compelled to leave their homes and work in harsh conditions which ultimately disrupted traditional ways of life and therefore leading as well to significant demographic changes.

This map also contains, in the upper left corner, a diagram representing the Andean (pre-colonial and even pre-Inca) dualist conception of the space in which the space is made up of two opposite yet complementary parts (upper and lower) articulated by a middle point (taypi). Accordingly, the high plateau, i.e. the plain in between the western and eastern ranges of the Andean mountains, was divided into an upper half (urcu) and a lower (uma) half with the Titicaca Lake as the middle point.4 Urcu has masculine, dominant and phallic connotations while uma has feminine, valley, humid connotations. Following this conception, the territories of Aymara polities were organized into two halves: the upper moiety and the lower moiety.

As can be seen on the map, the territories of the Qullas and of the Pakaxa were divided into the upper half (urco moiety) and the lower half (uma moiety). The Lupaqas only occupied the upper or urco side. It is also worth noting that by the time the Spanish colonial state established the capitanias de mita, there were a significant number of Pukina speakers embedded in these tributary units controlled by aymara speaking authorities. It seems that Pukina was the language spoken in the ancient (pre-Inca) civilization of Tiwanaku; the use of this language had disappeared by the end of Spanish colonization, early 19th century. Nowadays, the majority of the population inhabiting this area of the high plateau are Aymara speakers, mostly bilingual Spanish-Aymara.

REFERENCES:

Bakewell, Peter. Miners of the Red Mountain: Indian Labor in Potosí, 1545-1650. New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, 1984.

Bouysse-Cassagne, Thérèse. “L’espace Aymara: Urco et Uma.” Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 33, no. 5–6 (December 1978): 1057–80. https://doi.org/10.3406/ahess.1978.294000.

Domínguez Faura, Nicanor. “The Puquina Language in the Early Colonial Southern Andes (1548-1610): A Geographical Analysis.” Journal of Latin American Geography 13, no. 2 (2014): 181–206.

https://doi.org/10.1353/lag.2014.0033.

Nicanor Domínguez Faura, “The Puquina Language in the Early Colonial Southern Andes (1548-1610): A Geographical Analysis.” Journal of Latin American Geography 13, no.2 (2014): 181-206. ↩︎

Peter. Bakewell, Miners of the Red Mountain: Indian Labor in Potosí, 1545-1650. (New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, 1984) ↩︎

Dominguez Faura, “The Puquina Language in the Early Colonial Southern Andes (1548-1610): A Geographical Analysis.”, 181-206. ↩︎

Bouysse-Cassagne, “L’espace Aymara : Urco et Uma.” Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 33, no. 5–6 (December 1978): 1057–80. ↩︎