Abstract

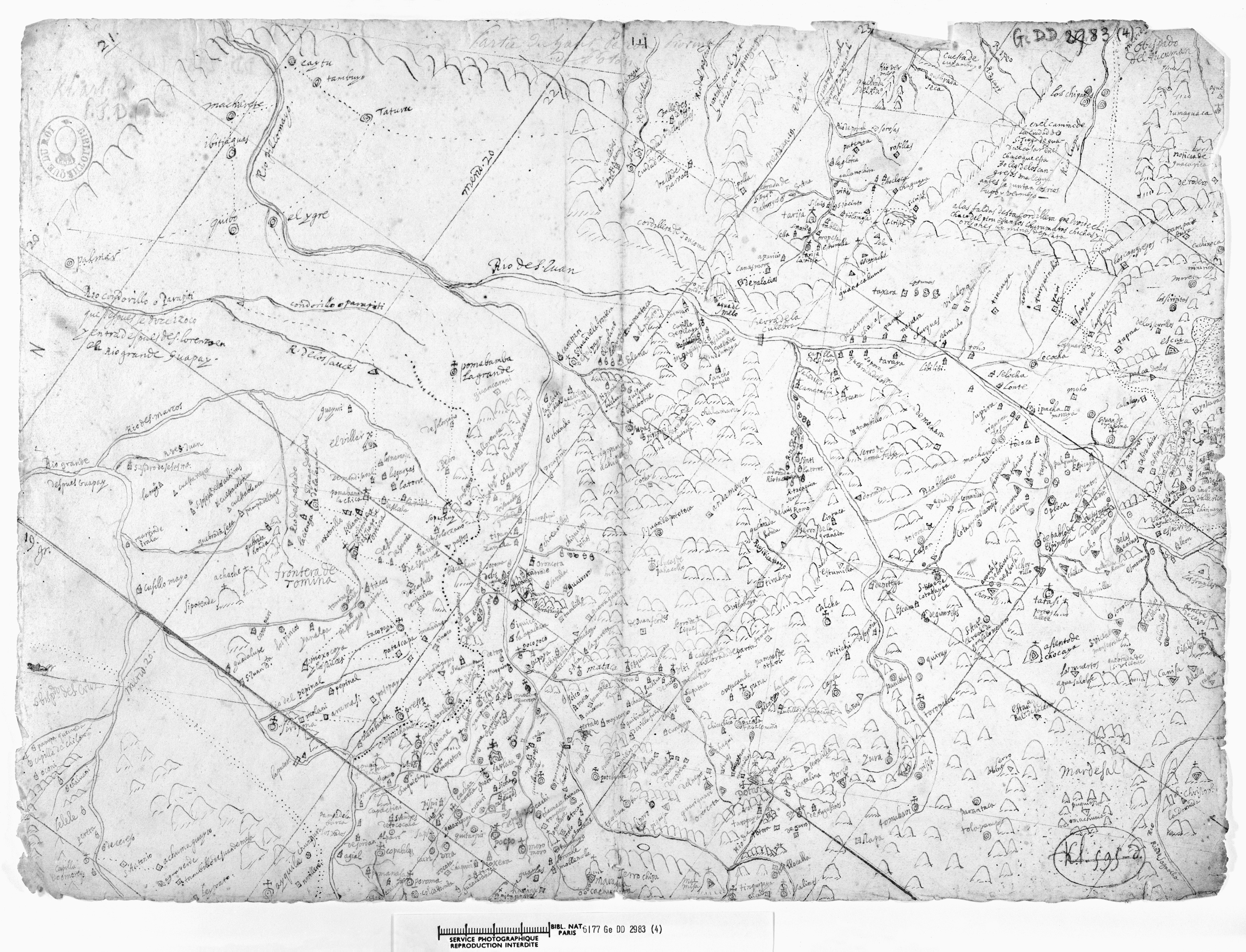

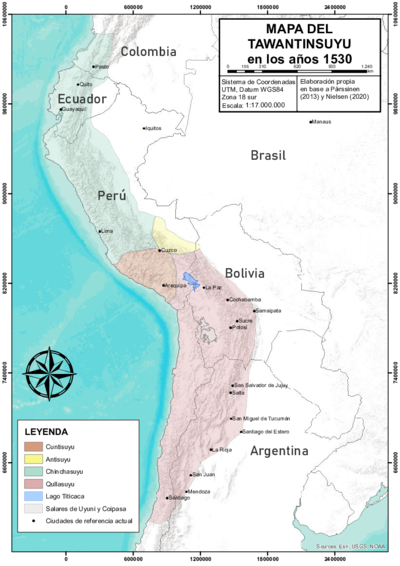

This 17th-century map, found in the National Library of France, is a detailed ecclesiastical cartography of an area of the Spanish colonial Archbishopric of Charcas, or La Plata, focusing on the city of La Plata, now Sucre, Bolivia, and its sphere of influence.[^1] The map also shows mining settlements and mountains that were once sacred sites for Indigenous peoples, both major scenes of the struggles for power and survival that took place in this part of the Andes after the Spanish arrival. The area shown on this map was part of the Audiencia de Charcas, the southern district of the Viceroyalty of Peru at the time. The vast territory of the Audiencia de Charcas was also known as Alto Peru and was famous for the rich silver mines of Potosí, hence the title of this colonial map. Today, the area shown on this map corresponds to the southern part of Bolivia (Chuquisaca, Potosí, Tarija) and the northern part of Argentina (northern Salta and Jujuy). In pre-colonial times, the area covered by this map was part of the [Qullasuyu](/en/content/BOL0002Y/), i.e., the southern district of the Inca state, or [Tawantinsuyu](/en/content/BOL0001Y/).The map displays a NW-SE (south is up) orientation, and presents about 525 geographical references on a single sheet of paper written in black ink, providing a detailed regional cartography. According to the study carried out, articulating pieces of information derived from the document along with documentary sources of the time and recent archaeological data, this map displays the following: 1) main towns and cities, 2) an overview of the eastern Andean slope, foothills and surrounding lowlands with their rivers and roads, 3) a portion of the highlands and valleys of Jujuy with information on Indigenous peoples and mines, 4) a repertoire of the main mining sites and mines known at the time, and 5) a list of mountains and hills —several of which Indigenous peoples considered sacred places.1

It is likely that the map may have been drawn by a church member with extensive knowledge of this ecclesiastical district. Its NW-SE orientation suggests an intention to represent a specific political space, such as an ecclesiastical jurisdiction, where some areas occupy a disproportionately larger space than others. However, despite its rudimentary aspects and scale distortions, this map appears to be a complete and accurate cartography for the time, with greater detail than later maps of the same space.2

REFERENCES:

Cruz, Pablo. “Reflexiones Corográficas a partir de un Mapa del Siglo XVII del Sur de Charcas.” Estudios Sociales del NOA, 15 (December 2015): 5-32.

Saignes, Thierry. “Potosí et le Sud Bolivien selon une Ancienne Carte.” Cahiers du monde hispanique et luso-brésilien 44, no. 1 (1985) : 123–28. https://doi.org/10.3406/carav.1985.2231.

selon une Ancienne Carte.” Cahiers du monde hispanique et luso-brésilien 44, no. 1 (1985), 123–28.

Estudios Sociales del NOA, no. 15 (Dic. 2015), 5-32.