Abstract

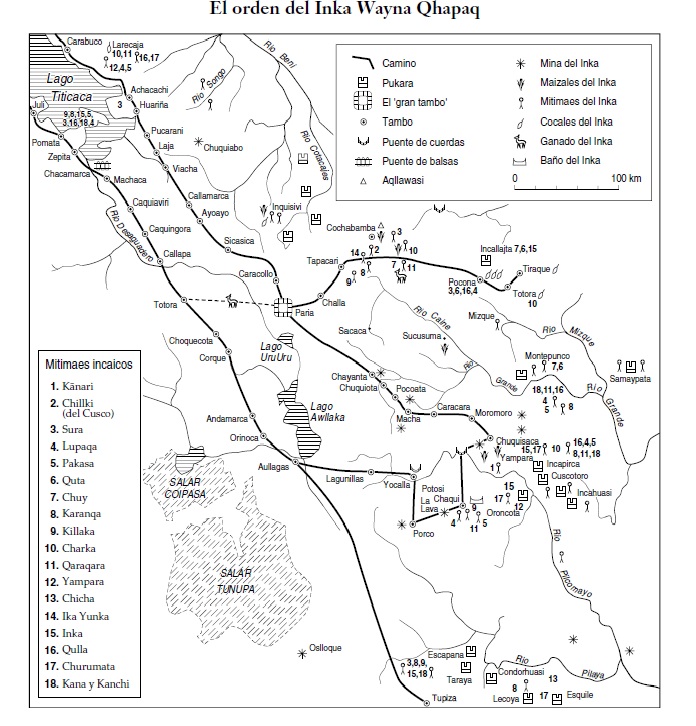

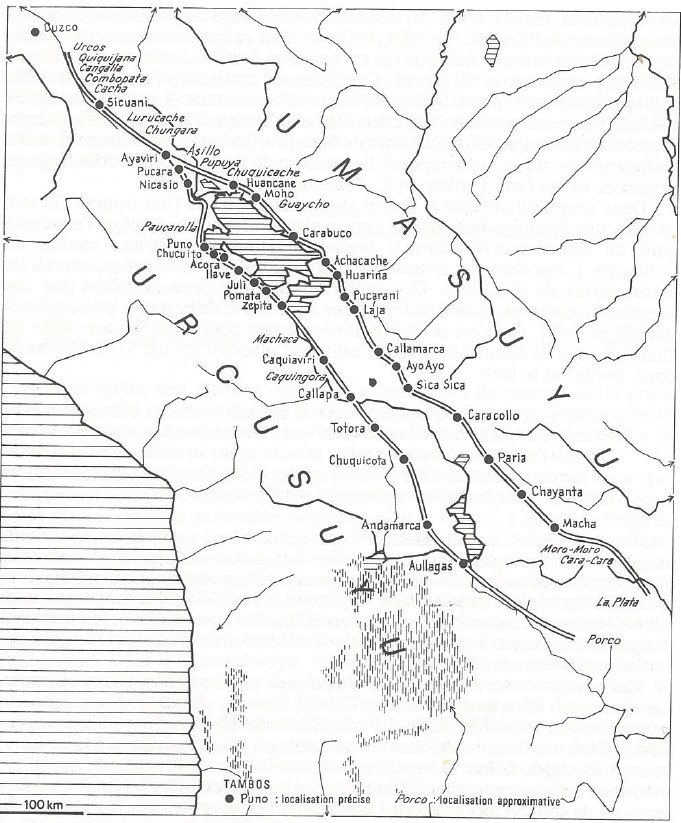

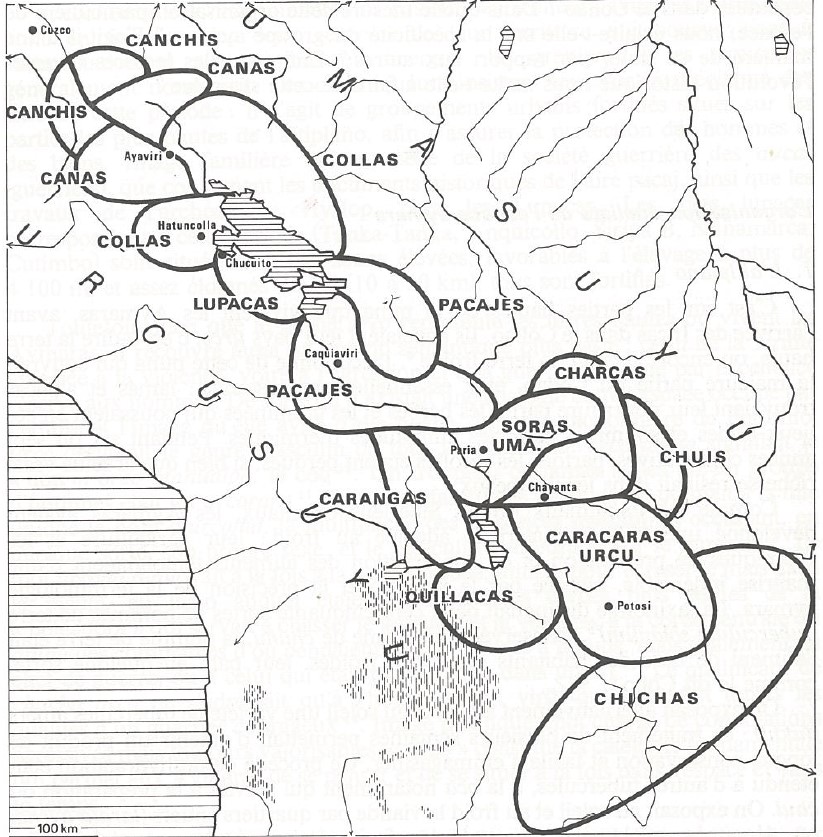

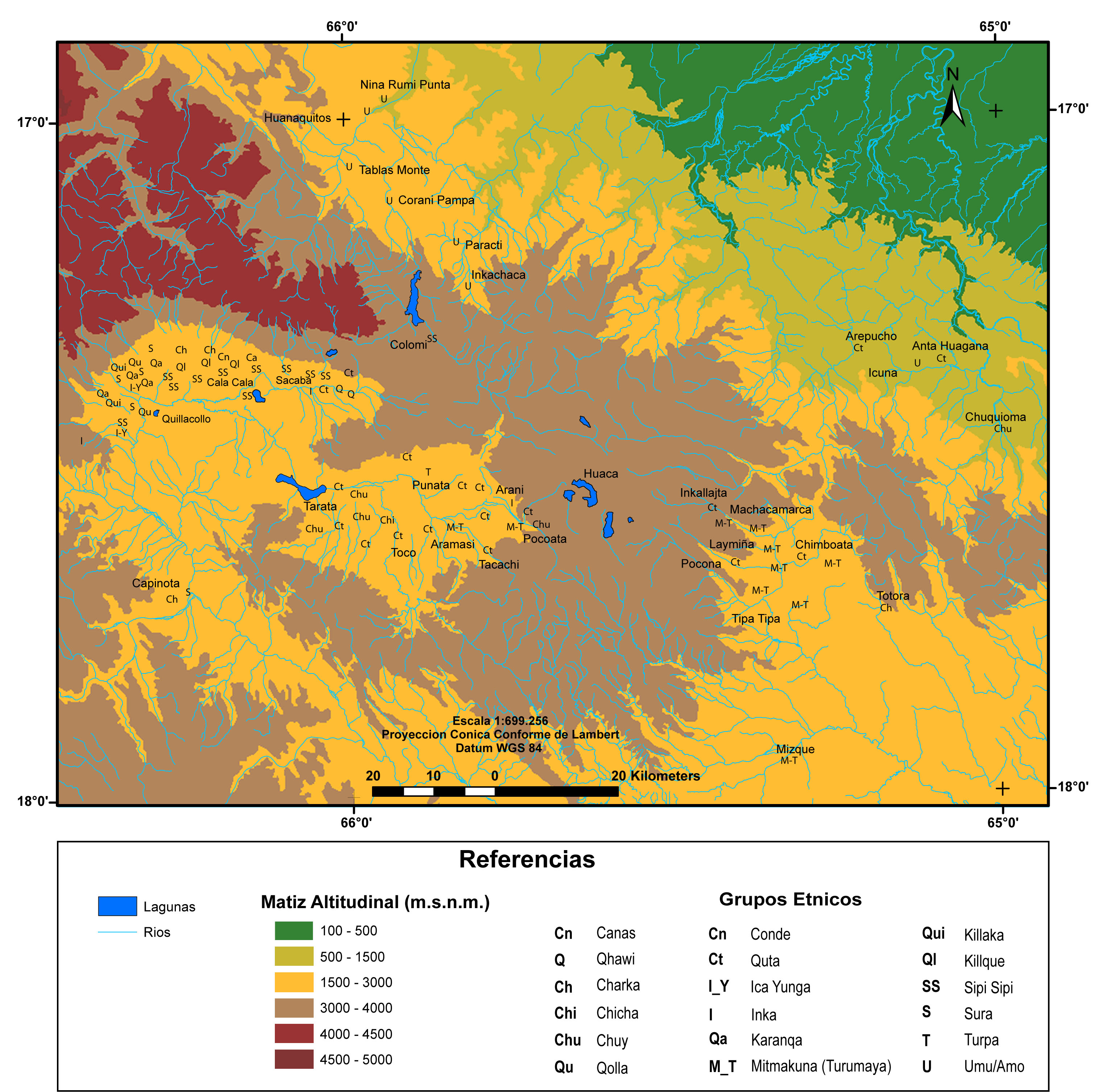

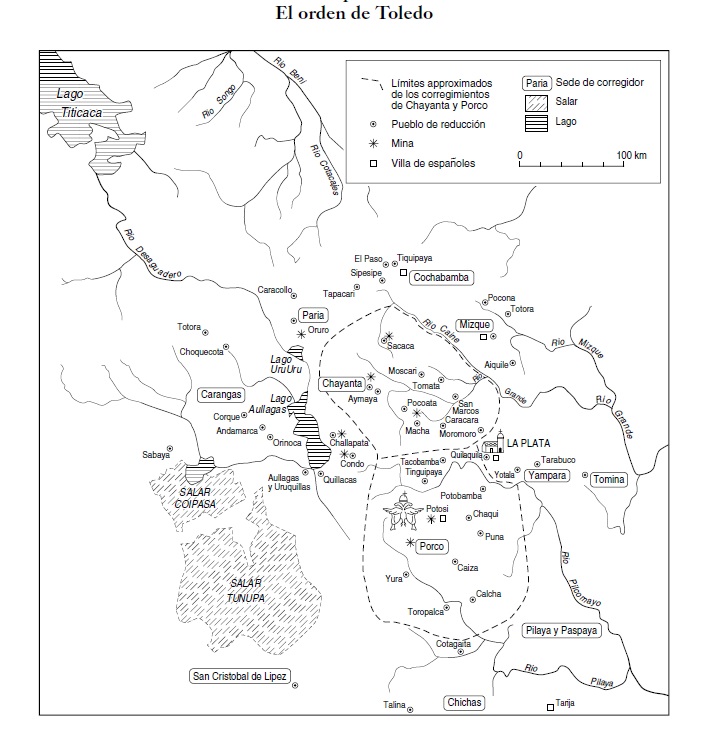

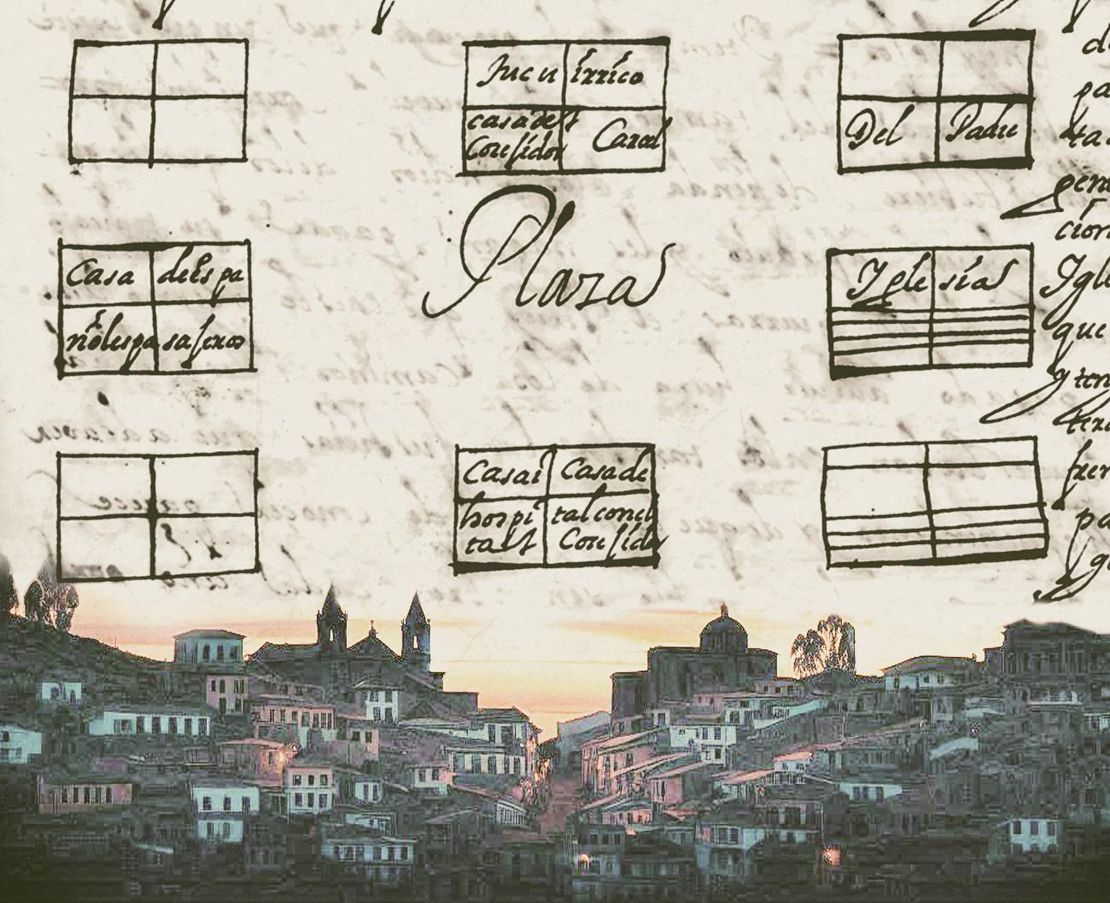

This map illustrates the organization and uses of the space of the southern district of the Inca state also known as the [*Qullasuyu*](/en/content/BOL0002Y/) portraying specifically the high plateau and the eastern inter-Andean valleys, just before the arrival of the Spaniards in the first decades of the 16th century.[^1] The map indicates: the'Inca Road' INCA ROADS AND TAMBOS in the 16th CENTURY network, the storage centers (or *tambos*), the bridges, the *aqllawasi* (specialized institutions in the Inca Empire, essentially “houses of the chosen women'' who were chosen to carry out specialized tasks in service of the state or the Incas), the Inca mines, the Inca coca and cornfields, the grasslands for the llama herds of the Inca state, and the baths of the Inca. It also shows the multi-ethnic territories MULTI-ETHNIC TERRITORY under INCA DIRECT RULE: THE CENTRAL AND UPPER VALLEYS OF COCHABAMBA in the 1530s , which were areas claimed as domains of the Inca state where the Incas resettled segments of population coming from the different Aymara polities AYMARA POLITIES of THE QULLASUYU in the 16th CENTURY of the Qullasuyu. Lastly, it shows the *Pukaras* (fortresses) built in Pocona, Samaypata, Cuzcotoro and Oroncota to contain the unconquered peoples, such as the Chiriguanos, and consolidate the territorial expansion of the Inca state, the [*Tawantinsuyu*](/en/content/BOL0001Y/). \Under Spanish colonial rule, in the late 16th century, the territory of the Qullasuyu became the Audiencia de Charcas following the new political administration of the Viceroyalty of Peru. The spatial organization under colonial rule POLITICAL ORGANIZATION OF SPACE UNDER COLONIAL RULE AT THE END OF THE 16th CENTURY profoundly altered the landscape shown in this map, particularly after the reforms implemented by Viceroy Toledo in the 1570s. Indeed, Toledo launched an ambitious program of massive, forced resettlement of ‘Indians’ into fixed ‘Indian royal towns’ known as reducciones to manage, evangelize, and tax the native population more efficiently. These reforms entailed the disarticulation of the large Aymara polities into fragmented “Indian communities’ and a profound reconfiguration of the organization and management of the space, a reconfiguration that responded to the requirements of the production of silver in the mines of Potosi and other mining centers across the high plateau.

REFERENCES:

Platt, Tristán, Thérèse Bouysse-Cassagne, and Olivia Harris. Qaraqara-Charka: Mallku, Inka y Rey en la Provincia de Charcas (Siglos XV-XVII): Historia Antropológica de una Confederación Aymara. La Paz: PLURAL-IFEA, 2006.