Abstract

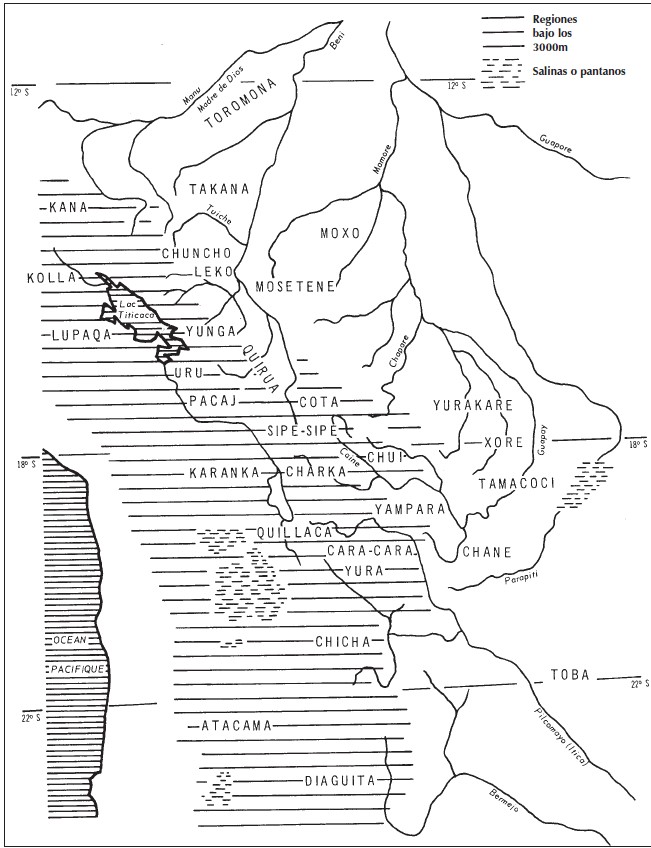

There is no consensus about the exact shape of the eastern borders of the Inca State, the Tawantinsuyu (see THE TAWANTINSUYU IN THE 1530s – TERRITORY OF THE INCA STATE ), but it is widely agreed that these borders were porous and unstable. This map, which depicts the southern district, the Qullasuyu (see THE QULLASUYU IN THE 1530s – SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF THE INCA STATE ), shows the Indigenous groups that inhabited this area in pre-Inca times, allowing us to identify those groups that lived along the eastern borders and interacted with the Inca State in various ways—through exchanges, warfare, alliances, etc.—but were never fully incorporated into it. The Indigenous groups shown to the far right of the lined area of the map were never conquered by the Incas (or by the Spanish) and include the: Toromona, Takana, Chuncho, Leko, Moxo, Mosetene, Yurakare, Xone, Tomococi, Chane, and Toba. All these groups were non-state societies that lived either in the tropical piedmont and plains of the Amazonian Basin or the drier, subtropical piedmont and plains of the Chaco region. It is worth noting that the word “chuncho” was often used as a generic term to describe all non-state societies living in the tropical piedmont and Amazonian plains.

The map’s legend is somewhat confusing, as it suggests that the lined areas represent regions below 3,000 meters in elevation—even though Lake Titicaca, depicted within the lined section, is actually located at 3,810 meters above sea level. It seems more likely that the lined areas actually represent regions above 3,000 meters. In any case, these areas roughly correspond to the territory of the Qullasuyu.

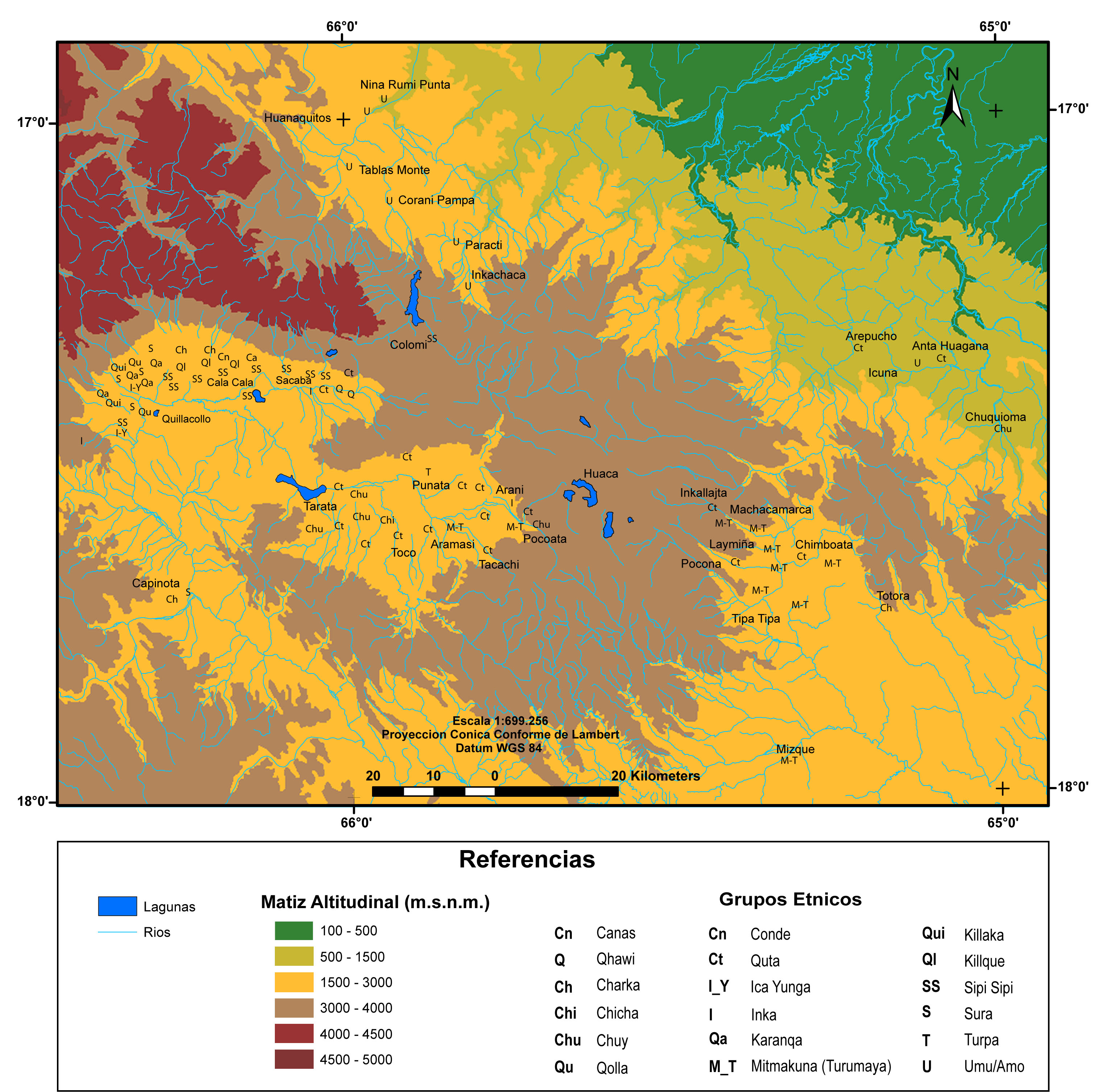

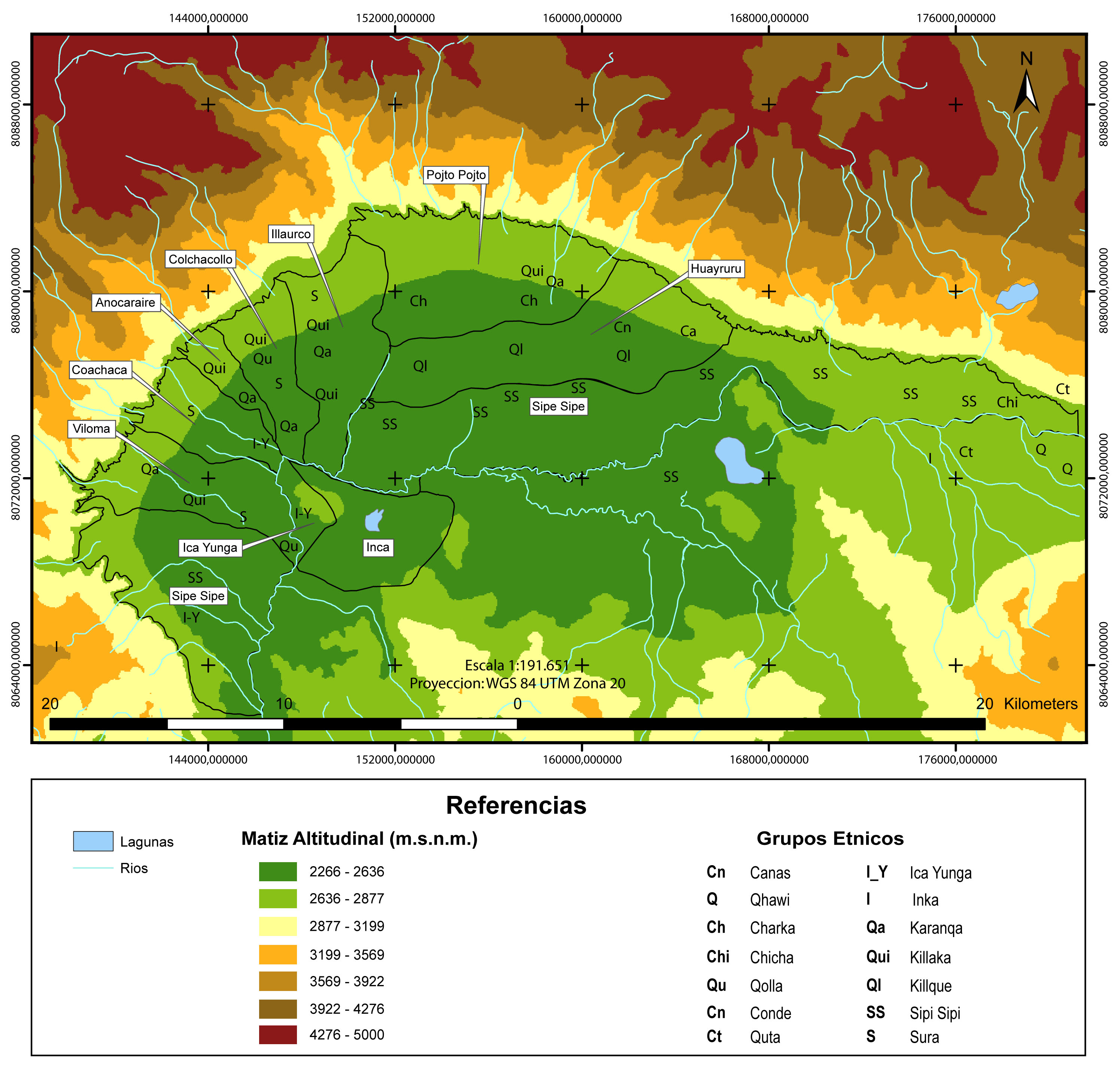

The expansion of the Inca State transformed the geography and human landscape of this vast territory in multiple ways. While Inca expansion north of Cusco stopped at the piedmont, south of Cusco it extended further down into the plains of the Amazonian basin and the Chaco region. The main strategy used by the Incas to expand this eastern border was to establish multi-ethnic colonies (see MULTI-ETHNIC TERRITORY under INCA DIRECT RULE: THE CENTRAL AND UPPER VALLEYS OF COCHABAMBA in the 1530s and MULTI-ETHNIC TERRITORY under INCA DIRECT RULE: THE LOWER VALLEY OF COCHABAMBA in the 1530s ) of people resettled from other regions of the Inca State. Through this resettlement strategy, the Incas created a buffer zone between Andean ethnic groups that occupied the edges of the piedmont (who were part of Tawantinsuyu) and non-Andean groups that remained outside the Inca State. This buffer zone policy suggests that by “occupying this intermediate no-man’s land, the Inca wanted to prevent direct communication between border neighbors” (own translation).1 Thus, we can visualize the eastern border of the Qullasuyu as a zigzag line running south through the piedmont, with inroads into the lower plains, dotted with Inca fortresses and multi-ethnic settlements.

Another significant event that altered the human geography shown on this map was the arrival of the Tupí-Guaraní people in the plains and piedmont of the Chaco region (between the Guapay and Pilcomayo rivers; 18°S – 20°S on the map) in the late 1400s and early 1500s, just before the Spanish conquest. Coming from what is now Paraguay and referred to as Chiriguanos by the Incas (and later by the Spanish), the Guaraní people posed a major threat to this southeastern border.

REFERENCES:

Renard-Casevitz, France Marie, Thierry Saignes, and A. C. Taylor. Al este de los Andes: Relaciones entre las sociedades amazónicas y andinas entre los siglos XV y XVI. Lima: ABYA YALA and IFEA, 1988.

France Marie Renard-Casevitz, et al., Al Este de los Andes: Relaciones entre las Sociedades Amazónicas y Andinas entre los Siglos XV y XVI (Lima: ABYA YALA and IFEA, 1988), 113. ↩︎